|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 228 |

Negative impedance is one of those things that simply doesn't get the attention it deserves. It all sounds very weird, but it's discussed in detail in the article Negative Impedance - What It Is, What It Does, And How It Can Be Useful. A negative impedance circuit is commonly referred to as a 'NIC' - negative impedance converter. This project only looks at one kind of NIC, and that's one that can be used to improve the performance of a signal transformer. Even the term 'impedance' is not correct - it's almost always a negative resistance.

If you spend serious money for a good audio transformer you'll get excellent performance, but if you only wish to experiment, you can get away with something much cheaper. There are 1:1 transformers available on-line for less than AU$2.00 each (600Ω nominal impedance). Their DC resistance is fairly high and their inductance is a bit too low to be useful at more than a couple of hundred millivolts. While it's not possible to make them perform like a high-quality transformer, they can be improved to the point where they can be used for hi-fi. Whether you do use a cheap transformer for hi-fi is up to you of course, but you'll likely be surprised at the improvement you can achieve.

You'll find articles elsewhere that claim that transformer distortion is part of the 'analogue sound', and is therefore sought after. In general this is bollocks, because good transformers add so little distortion that it's unlikely that it would be audible in a double-blind test. When transformers distort, it's almost exclusively at very low frequencies (less than 40Hz), which are usually at a fairly low level in most music.

This project is designed to let you experiment, using (almost) any transformer designed for audio. If you use a really good (and therefore expensive) transformer, it can be made even better. A cheap transformer can be forced to perform well by cancelling out the primary winding resistance with a NIC. The general idea is covered in Transformers For Small Signal Audio, which also has several oscilloscope captures showing how effective negative impedance can be.

The theory behind all of this is down to transformers themselves. An 'ideal' transformer has no winding resistance, and if driven from a zero-impedance source has no distortion and no lower frequency limit (up to a point). The effects of the onset of saturation are entirely due to the combination of source impedance and winding resistance, so by applying a negative impedance source, the winding resistance effectively 'ceases to exist' when the two are equal. It's necessary to keep the negative impedance/ resistance just a little lower than the 'real' positive resistance to prevent the possibility of instability. If the transformer has a primary winding resistance of 100Ω, the source impedance should be no more than around -98Ω.

All of this might sound far-fetched or at least wishful thinking. I can assure you that it's not, but to understand it and see it for yourself is invaluable. There are caveats (there are always caveats), but they usually don't get in the way of successful testing if you follow the guidelines. The primary and most important of these is to ensure that the negative impedance is always less than the positive impedance. If the combined impedance is negative, you'll create an oscillator!

Negative impedance is an unstable state for an electronic circuit, and it has been used to create oscillators for a number of applications. Tunnel diodes, DIACs and neon lamps are examples of devices that exhibit a pronounced negative impedance region, and all can be made into oscillators quite easily. This is (usually) not what you want to achieve, but of course you can do it just to prove it to yourself. The load should not be resonant - A resonant circuit and negative impedance results in an unstable system.

With a normal linear circuit, when the output is loaded the voltage falls, due to internal (positive) resistance. When the impedance is negative, the output level will increase when a load is applied. This forms part of the definition of negative impedance/ resistance. If you use Ohm's law to determine the voltage division formed by two equal values - the division is two, but when one is negative that becomes zero. Negative impedance is achieved by using positive feedback.

I tested two transformers thoroughly, with the following measured characteristics ...

| Transformer Type | RPri | RSec | LPri | LLeak |

| $2.00 eBay 600 Ω | 133.1Ω | 133.6Ω | 1.08H @ 100Hz | 143µH @ 100kHz |

| 600 Ω Telecomm | 53.6Ω | 66.3Ω | 2.8H @ 100Hz | 1.7mH @ 100kHz |

The second transformer has been used in other tests and described in referenced ESP articles. Although designed specifically for telecommunications applications, it can perform surprisingly well when driven by a NIC. The '$2.00' transformer is readily available on eBay for AU$2.00 or less, depending on quantity. It would normally only be suitable for the most basic of applications, but by adding a NIC it's capable of good performance provided the level is kept fairly low (around 1V RMS is the maximum I'd recommend).

| Also see P228 Annex - Distortion Cancellation A brief look at the mechanism that creates distortion, and how it can be cancelled (at least in part). |

The project itself is fairly simple, but there is one main requirement. This is output current, as a transformer that's entering saturation will demand much more current than most opamps can provide. The ideal is a pair of NE5532 opamps in parallel (i.e. one 8-pin IC with the two opamps in parallel). You can use a 'better' opamp of course, but the LM4562 (for example) is more expensive and won't actually be much of an improvement. The project described uses three opamp sections in parallel.

To make testing as simple as possible, the first stage should provide variable gain. I leave it to the constructor to decide on the opamp used, but the NE5532 is recommended. The other half of the opamp is used for the NIC. Another NE5532 is used to further improve current output. This will allow the circuit to drive a 200Ω load, with up to 50mA output current within the opamp's linear range. We can get a great deal more as shown in Project 113 (headphone amplifier), but it's more complex than the simple paralleled opamps and not necessary.

Two NICs are shown above, but as basic concepts. Version 1 is usually a better choice for a final circuit, but only if the opamp has very low offset voltage. For this project, I elected to use Version 2, as the output capacitor blocks any DC offset completely. R3 in Version 1 does change the output impedance very slightly, but it's of no account for a NIC driving a transformer. A capacitor is essential, because without it there can be significant gain at DC, which will increase any offset voltage dramatically. The capacitor ensures that the circuit has unity gain at DC.

C3 is optional, and it may be required with some transformers. There is a possibility (as I found during testing) that some transformers will cause the NIC to oscillate, and C3 reduces the amount of positive feedback at high frequencies. This isn't something I'd encountered before despite many such tests over the years, but it happened with the second transformer I tested (1:1 10kΩ nominal impedance). This transformer has a relatively high primary resistance of around 380Ω, and the NIC was not happy with that.

The negative output impedance is equal to the value of RZ-. If it's 50Ω then the output impedance is -50Ω. If a normal resistor is used as a load, when the load and negative impedance are equal, and the circuit 'sees' a short-circuit. In theory (and if 'ideal' opamps were available), the output voltage would be infinite, along with infinite current. In reality the circuit will attempt a gain of several hundred if RL and RZ- are equal, and the opamp will distort.

The gain with no external load is unity (actually -1 as it's an inverting stage). With a 1k load and RZ- of 100Ω, the voltage across the load can be measured or calculated. To verify this with a 1V input ...

I = V / R

I = 1 / 1k - 100 = 1.111mA

The 1k load is no longer 1k, because 100Ω has been subtracted by the NIC. This is what the circuit is meant to do, and it performs as theory dictates. Note that the load cannot be grounded, as that bypasses RZ- so there's no positive feedback. The voltage across RZ- is (not surprisingly) 111.1mV. The output coupling capacitor is 2 x 1,000µF electros (10V rating is fine, so they're not large). This is needed because there will always be some DC offset from the opamps. The polarity is not important because the voltage across the caps will be only a few millivolts. Even a small amount of DC in a transformer winding can cause problems, so capacitive coupling is essential. The coupling capacitor also limits the DC gain to unity, especially important when RL and RZ- are close to being equal.

There are complex interactions between the positive and negative feedback networks, but expect trouble only if RL and RZ- are exactly the same value, or if RZ- is greater than the transformer (or other load) DC resistance. Even a couple of ohms will cause problems, but this isn't the way the circuit is meant to be used. With equal values of positive and negative impedance, the circuit is conditionally stable. Even a small change (connecting or disconnecting a load or temperature changes for example) may cause the circuit to oscillate at a frequency determined by the opamps and physical circuit impedances (especially transformer inductance and capacitor value).

Much of this will become apparent when you use the circuit. You need an oscilloscope to be able to see the effect (distortion reduction), along with a signal generator so you can test the circuit (and the transformer) at the lowest frequency you wish to pass. This will generally be between 20Hz and 40Hz, depending on your requirements. A means of measuring the output distortion (both with and without negative impedance) is useful, but not entirely essential. You will want to listen to the results, especially when driving a higher voltage than the transformer can normally handle at low frequencies.

The circuit consists of a variable gain amplifier (U1A) followed by the negative impedance driver stage (U1B). U2A and U2B are used as 'slave' buffers to increase the output current. Each will buffer the voltage appearing across R5. The three opamp sections are effectively in parallel, with the outputs protected against circulating currents by 10Ω resistors. As a transformer is driven into saturation the current increases quickly. The paralleled stages ensure that you don't run out of drive current while testing. In 'normal' use, a single opamp is all that's needed, but this is a test circuit and should be able to push the transformer to its limits (and beyond). Doing this in a final circuit is ill-advised.

Sw1 (A/B) is optional. It allows you to bypass RZ- to do an A/B comparison. The output level shouldn't change at all (or if it does, it's a tiny amount), and you can switch the NIC in and out of operation to compare the difference. In tests I did (using a clip lead instead of the switch) you can hear the difference easily with low-frequency sinewaves. It's not 'chalk-&-cheese', but the difference is definitely audible. The point marked 'Note' is potentially useful. If you add a switched 180Ω resistor in series with the pot (break the connection where the arrow is pointing), you can test transformers with up to 380Ω winding resistance. This is entirely optional.

The gain is set by VR1, which gives a range from zero to x10. It's inverting so the final output is in-phase, as the NIC section is also inverting. The block shown as 'TP1' is only needed if you put the circuit in a case. This lets you measure the resistance of VR2 with an ohmmeter (you can also measure between 'Out-' and ground). Be aware that the circuit is not designed for particularly high frequencies, as the two 'slave' opamp stages may not be able to follow the 'master' accurately at more than ~10kHz. This is the highest frequency you're likely to need, but my tests indicate that it will go higher without any issues. I tested it to 50kHz without any apparent problems.

The idea is that you should set the (negative) output impedance to be just a little less (greater?) than the transformer's primary winding resistance. The winding resistance is then effectively (mostly) cancelled, improving performance. The output impedance is set with VR2, and I suggest a 200Ω pot if you can get one. It's unlikely that suitable transformers will have a DC resistance greater than 200Ω, but it can be changed if your requirements are different. With higher resistance comes a voltage limitation as well. The negative impedance resistor (RZ- - VR1) will have a voltage across it, which has to be added to the opamp's output voltage to get the designated voltage across the transformer's primary winding. As the resistance of VR1 increases, so does the output level from the opamp drive circuit.

In case anyone is wondering, I used a multi-turn 200Ω pot that I had in stock. Unfortunately, these are expensive if you have to buy one. Otherwise, use a 200Ω multi-turn trimpot. This is a less convenient option, but setting it is easy enough and it doesn't need to be changed unless you wish to test a different transformer. A multi-turn pot also lets you tweak the resistance in operation while monitoring distortion. I managed to get my test transformer down to 0.15% THD at 30Hz when RZ- was exactly the same as the primary resistance (see below for more realistic test figures).

In case you're wondering how this can possibly work with a transformer, remember that most of the impedance seen by the drive circuit is 'real', and is the reflected impedance from the secondary. If a nominal 600Ω transformer is loaded with (say) 2.2k, the total secondary impedance as seen by an 'ideal' primary is 2.2k plus the secondary winding resistance. Transformers do not have an intrinsic impedance - the whole idea of specifying the impedance is to allow a defined inductance to be determined. For example, a 600Ω transformer with a -3dB response of 20Hz requires an inductance of ...

L = Z / ( 2π × f3 ) (Where f3 is the -3dB frequency)

L = 600 / ( 2π × 20 ) = 4.77H

As the nominal impedance is increased, you need more inductance for the same -3dB frequency. The maximum level and minimum frequency that a transformer can handle is determined by the size of the core. Magnetic materials have an upper limit on the maximum flux density before saturation, and for low distortion the peak flux must be far less than that which causes even partial saturation. Small transformers can have good low frequency response, but only at low signal levels. As the level is increased or the frequency is reduced, the core will start to enter the saturation region and the output becomes distorted.

If a transformer is driven by a negative impedance so the primary winding resistance is cancelled, it will operate to a lower frequency and at a higher level. Transformer core saturation is not reduced (for a given peak current), but it's effects are reduced because the waveform distortion reflected by the primary resistance is minimised. If the primary resistance is cancelled, the distortion cannot influence the voltage waveform. Of course the distortion is still there, but the NIC provides a 'pre-distorted' signal that effectively cancels the transformer's distortion. You have to try this for yourself to understand that it's true. Theoretical analysis will also provide proof, but that's intangible.

Transformer impedance is a topic that seems to confuse a great many people. The first thing to remember is that a transformer has no impedance of its own. All signal transformers are designed around inductance and flux density, and these determines the low frequency and voltage limits. The vast majority of signal transformers are driven from a voltage source (low to very low impedance). This will usually be an opamp, but it may be something a little more 'powerful' such as a high-current line driver. Impedance matching is rarely used in audio circuits (other than for 'old-school' telephony). Most sources are low impedance and most inputs are (comparatively) high impedance.

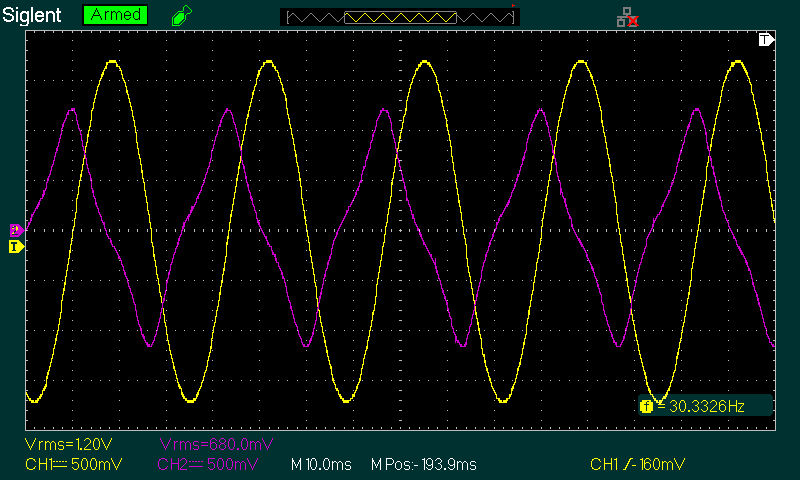

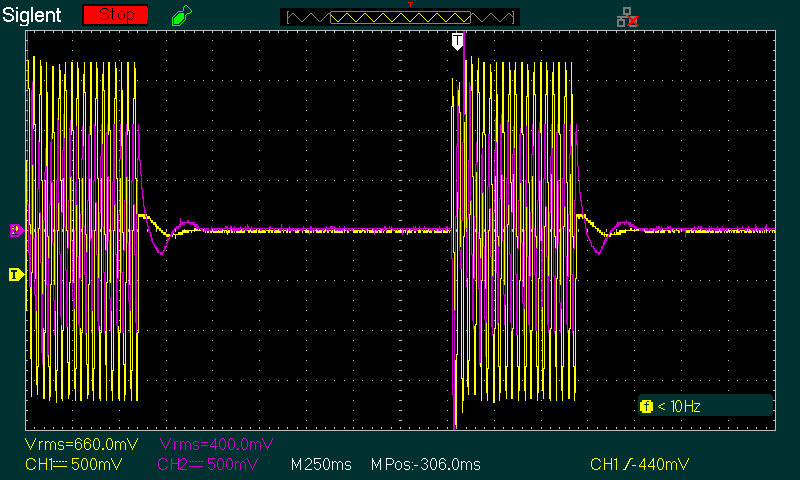

I ran tests on a few transformers, the two shown in Table 1, and another of 'medium quality'. The cheap transformer used was a $2.00 1:1 600Ω type, purchased from eBay. When driven at 1.2V RMS direct from an opamp, the distortion at 30Hz was 7%, well outside the limits of what anyone would think is acceptable. The waveform using a NIC is shown below, with the yellow trace being the transformer's output, and the violet trace showing the voltage across VR1. It's very easy for the current to exceed the capabilities of the opamps, but it would not be sensible to push the NIC or the transformer that hard.

When you look at transformer specifications, always check the signal level used for measurements. For '600Ω' transformers, this will often be at 0dBm (1mW at 600Ω, 775mV RMS). This was a standard level, and came from the telecommunications industry. Most levels now are referred to either 0dBu (775mV) or 0dBV (1V). Many transformer interfaces are expected to provide a higher level, and +4dBu is common for pro-audio equipment (1.228V RMS). Consumer audio equipment is generally at a lower level, with -10dBV (316mV RMS) said to be common, but this isn't a 'controlled' parameter and much equipment will be very different.

An example test setup is shown above, using the Fig. 2 NIC circuit. When VR1 is set to 130Ω, the primary winding resistance is (mostly) cancelled, and the distortion at the transformer's output is greatly reduced. In the 'perfect' case, negative and positive resistances will cancel completely, leaving no distortion at all. Reality will be different because opamps don't have infinite gain, so complete cancellation isn't possible. However, the performance is improved quite dramatically, as evidenced by a real test with the waveforms shown below. With VR2 set to 133.6Ω (exactly the winding resistance) the distortion is reduced further (~0.1% THD @ 30Hz and 1.2V RMS), but that's at the very limits of stability and isn't recommended.

You can see from the violet trace that the transformer primary current is non-linear, and it shows the saturation behaviour of the transformer. The NIC effectively removes the primary resistance, so the primary (and the secondary) 'see' a nice sinewave. The distortion is not passed through to the secondary, and the current waveform cancels the non-linear voltage impressed across the primary winding. The whole idea of using the NIC is to make the primary resistance as close to zero ohms as you can get, so the voltage waveform remains 'clean'. The current waveform is almost incidental.

The peak saturation current occurs at the voltage's zero-crossing point. This is always the case. The saturation current peaks at just over 9.2mA (1.2V peak and 130Ω). As noted above, it's essential to keep the negative impedance a little less than the transformer's primary resistance, or the system becomes unstable. This was very obvious in the tests I performed, and the instability can be extreme.

With the NIC in circuit and with 1.2V RMS at 30Hz (+3.8dBu), the distortion is reduced to 0.35% (from 7% without the NIC), and we know it's a lot less at higher frequencies. Transformer saturation distortion only occurs at low frequencies, and is generally considered to be comparatively unobtrusive. Compared to any amplifier's clipping distortion this is certainly very true, and countless early low-cost mixing consoles (for example) have proven that. These used (usually cheap) transformers because the transistor circuitry of the day couldn't provide a satisfactory electronically balanced input stage.

There's something that always occurs when a transformer and NIC are combined, and this can be seen with a tone-burst signal. This is a much harsher test than any music, because the signal stops and starts instantly, and it starts from zero voltage. Transformers don't like having their input starting from zero at maximum level, because that creates an inrush current 'event'. The effect is visible at the start and end of a burst (20 cycles of 30Hz at 1.2V RMS), but with music this is not audible because no music has such rapid transitions from nothing to maximum and back to nothing. The effect occurs even without the NIC, but it's less pronounced.

The 'medium quality' transformer was far more impressive. I haven't included 'scope traces, but I was able to get very clean response down to 20Hz at an output level of 3V RMS. The distortion at 20Hz was only 0.04%. Without the NIC this increased to 0.4% (which is still pretty good), so it's obviously a worthwhile exercise. In general (and not surprisingly) a better transformer to start with gives a better final result, and with less potentially unstable negative impedance. Getting the best result possible must take second place to circuit stability!

One thing that came as a real surprise showed up when I ran a test at 400Hz with the $2.00 transformer. This was done to make sure that the distortion wasn't made worse by the NIC. I know that transformers are usually pretty good in this regard, but I didn't expect to see distortion so far below my measurement threshold that it was (for all intents and purposes) zero. A quick adjustment of the impedance pot showed that I could null the distortion, with the minimum (unsurprisingly) when the NIC output impedance was exactly the same as the transformer winding resistance (but negative). The nature of the distortion cancelled in this way is unknown (the voltage across VR2 was just a sinewave), but I expect that it was due to hysteresis losses in the ferrite transformer core. I didn't see any noticeable distortion at higher frequencies with any of the other transformers I tested (including a mains transformer used in reverse). All transformers showed a significant reduction of distortion with the NIC at 40Hz (my 'benchmark' for these tests).

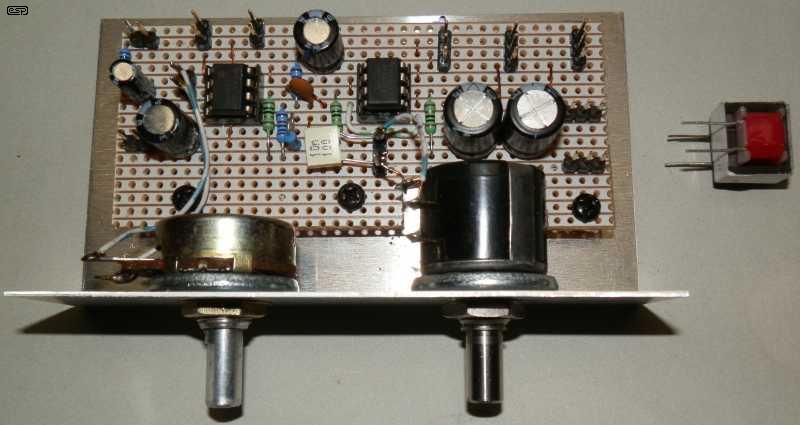

The photo shows the unit I built, with the $2.00 test transformer to the right. The circuit is exactly as shown in Fig. 2, except I used a 50k pot for VR1. As I mentioned before, this is as close to a 'case' as the circuit will ever get - the open chassis lets me attach test leads to the termination points, so I don't have the extra hassle of input and output sockets. I can clip a multimeter directly to VR2 to measure resistance. There's not even any need for knobs, as the pot shafts work just fine.

It's not 'pretty' but it does exactly what I wanted it to do, and it can drive 60mA (peak) through the transformer without distorting. The NE5532 opamps are ideal, and the two 1,000µF output capacitors block any DC from the transformer. It's also very easy to monitor the two important circuit voltages, namely the opamp output voltage (pre-distorted to cancel the distortion in the transformer), and the transformer current (across VR2). It's been tested up to 100kHz, although it will never need to operate at more than ~10kHz in use.

A complete circuit for 'finished product' (high-pass filter and NIC) is shown above. The filter prevents any excitation at low frequencies, and should be used whether you include a NIC or not. The value of RZ- is dependent on the transformer, and the value is confirmed using the test circuit. As noted already, RZ- should be a little less than the transformer's primary resistance - about 5% is usually fine. You can use a trimpot if preferred, and that makes setting the value far simpler than trying to find an obscure value resistor. You get a bit more distortion, but the circuit will remain stable. The filter has a cutoff (f3) frequency of 15Hz, and will be 1dB down at 20Hz.

The input to the filter must be low impedance, and it will typically come from another opamp in the system. C3 isn't essential, but it's recommended. Any DC in the transformer's primary winding will cause premature and asymmetrical saturation. The final arbiter of the usefulness (or otherwise) of any circuit like this is "can you hear a difference?". Listening to music on my workshop system (not hi-fi), the $2 transformer had slightly better bass response, but nothing that can't be compensated with a bit of EQ. With sinewaves, the answer is a definite "yes". Even at 100Hz where saturation distortion is negligible, without the NIC some distortion was audible. Even more so at 40Hz. Whether you use it or not is personal choice, but IMO it's worthwhile.

Ideally, any transformer should be loaded with an impedance that's around 10 times its nominal impedance. A 600Ω transformer will therefore be loaded with either 5.6k or 6.8k. This isn't critical, but beware of using anything much lower, as the output level will be reduced, which reduces the signal to noise ratio. Remember that impedance matching is not required unless you're running cables several kilometres in length. This is uncommon other than in telephony. In that field there's a parameter known as 'return loss', but it's not relevant for home or studio audio circuits.

This project will almost certainly have limited appeal, which is a shame because it's so interesting. For anyone who likes to experiment with ideas s/he may not have though about, negative impedance is a fascinating topic. The project isn't expensive to build, and you can use any dual power supply you have handy to power it. It's unlikely that anyone will need it so often that it's worthwhile to build a supply into the case it's in, and it's likely that it won't even get a case at all (mine certainly will never get a 'proper' case).

The layout will typically use Veroboard or similar, and with only two opamps it's fairly cheap to build. Extreme precision isn't needed for the resistors, but I do suggest using 1% metal film types. These are quieter than carbon film, and have very low drift. If you work with signal transformers regularly (or would like to), you'll find this project very useful. Even if you only build it to experiment with a NIC it's still educational. If you connect a resonant circuit to the output (e.g. an inductor and capacitor in series) you have a negative impedance oscillator.

You can use a NIC to get better performance from a transformer than would otherwise be the case. It comes with extra complexity and important conditions, in particular that you can never cancel the primary resistance completely, so the transformer will still have some distortion. As shown by the test results, it's easy enough to reduce the distortion by as much as an order of magnitude, and that's a very good result. In electronics (and life) nothing is ever 'perfect', but the use of a NIC can transform a very ordinary transformer into something a lot better. That can't be a bad thing.

In the final transformer drive circuit (developed after you run some possibly brutal tests), you will reduce a transformer's distortion, and increase its low-frequency response, but using a simpler circuit (such as that shown in Fig 1, Version 1) that provides response and output level that is 'acceptable'. What is deemed acceptable depends on what you're trying to achieve and the end use of the final product. No signal transformer will ever be perfect, even those costing a great deal more than the ones I tested. In most cases, a moderately priced transformer can be made to perform as well as a 'top shelf' component, and the latter can be made even better.

When you use any transformer driver, beware of series resonance if the output is capacitively coupled (this applies if you use a NIC or a 'normal' transformer driver). If a transformer has an inductance of 4 Henrys and you use a 1,000µ coupling capacitor, resonance is at 2.5Hz, and there will be a very large boost at that frequency. Transformer drive circuits should always use an infrasonic (high-pass) filter, with no less than a 12dB/ octave rolloff at the lowest frequency of interest. If you need response to 20Hz, the filter should be tuned for about 15Hz (~1dB down at 20Hz). If you use an opamp with very low DC offset, it's better if you omit the capacitor, but I still recommend using a high-pass filter.

Happy experimenting!

As a side-note to the above, some people may imagine that a NIC would be ideal for driving a loudspeaker. I've tried this and documented the results [4, 5], and it's fair to say that it's ill-advised. Remember that a NIC coupled to a resonant circuit is the basis for some oscillator designs, and a loudspeaker driver has a pronounced resonance. The final referenced article was done many years ago (I had to take photos of my 'scope screen at the time), but shows very clearly that it's not a good idea. That hasn't stopped anyone else from trying it, but there's little useful material on the Net.

There are no external references, as the techniques described have all been described elsewhere on the ESP website. There's some information on-line, but it's primarily theoretical, and almost no-one else has applied it to audio signal transformers. ESP articles on the topic are ...

Also see P228 Annex - Distortion Cancellation A brief look at the mechanism that creates distortion, and how it can be cancelled (at least in part).

Main Index Main Index

Projects Index Projects Index

|