|

| Elliott Sound Products | Electric Motors |

)

) Main Index

Main Index

Articles Index

Articles Index

Motors are very much a part of life, and are used almost everywhere. They range from tiny flea-power types for quartz electric clocks, to CD and DVD players, computer hard disk drives, to large industrial machines that may be rated for 1MW (1,000kW or 1,340HP) or more. They are used to start internal combustion engines, power the electric seats, door locking mechanisms, through to powering the car itself for 'fully electric' and hybrid cars. One of the most common types is still the brushed DC motor, which has been with us for over a century, and shows no sign of going away anytime soon.

The most common AC motor is the 'squirrel cage' asynchronous motor, originally patented by Nicola Tesla in 1888 [ 1 ]. These have been refined consistently over the years, and are the most common motor for light industrial machines, refrigerators, washing machines and other similar tasks. In many areas they are being replaced by electrically commutated motors (commonly referred to as BLDC motors). Another very common motor is the shaded-pole type, and these are found in exhaust fans, small pumps (dishwashers, washing machines, etc.) and in many other places where a more robust motor isn't needed. They are used in many pedestal fans, in particular the cheap 3-speed types.

A shaded pole motor is actually a variation on the squirrel-cage motor, but with greatly reduced size and power. Despite initial appearances, all motors use much the same operating principle, although there are often some subtle (but important) differences. Motors rely on magnetism (or more correctly, electromagnetism), which is either switched or produced by AC input power. All AC induction motors have a synchronous speed, which depends on the AC frequency and the number of poles. A 2-pole motor fed with 50Hz AC has a synchronous speed of 3,000 RPM (3,600 RPM with 60Hz), but the majority of AC motors are not synchronous - they rely on 'slip'. The rotor slows under load, inducing a current into the 'squirrel cage' rotor that generates a magnetic field in the rotor, allowing the motor to produce torque (rotary force).

The first commutator DC motor capable of powering a machine was invented by the British scientist William Sturgeon, in 1832. Following the work of Sturgeon, Thomas Davenport built an improved DC motor in America, with the intention of using it for 'practical purposes'. This motor, patented in 1837, rotated at 600 RPM and operated light machine tools and a printing press [ 2 ]. The basic principles haven't changed, but modern motors are far more efficient than these early attempts.Something that isn't covered here is the interaction of magnetic fields that causes a motor to rotate. This is a deliberate omission, because it's assumed (rightly or otherwise) that the reader already knows the basics of magnetic (and electromagnetic) attraction and repulsion. A rotor has a North and South magnetic pole that changes continuously, and this is attracted to its opposite pole on the stator, and repelled by a like pole. All motors (whether AC or DC) use this principle, and DC motors use a commutator (see below) to ensure that the poles can never reach static equilibrium - therefore the motor is in a constant state of trying to catch up, resulting in rotation. AC motors are much the same, except that (usually) it's the magnetic field in the stator that 'rotates'. This basic understanding is all that's necessary to be able to follow the descriptions here. Ultimately, it's all based on the magnetic rule that ...

Like poles repel, unlike poles attract.

It makes no difference if the magnetic field is due to permanent magnets (ferrite ceramic, AlNiCo [Aluminium, Nickel, Cobalt], NdFeB [Neodymium, Iron, Boron], Samarium–Cobalt, etc.) or electromagnets (coils of wire, with or without an 'iron' core). Motors can use only electromagnets, or may use permanent magnets and electromagnets. You cannot make a motor that uses only permanent magnets, because there's no way to change the polarity of the magnetic field, and therefore no way to generate movement. Contrary to belief in some circles, magnets are not a source of energy, thus rendering all 'perpetual motion' (aka 'overunity') machines into concentrated snake-oil.

Permanent magnets use 'hard' magnetic materials, meaning that once magnetised, very little field strength is lost over time, or due to the influence of external magnetic fields. These materials are specifically designed to have high coercivity - the ability to retain magnetism without becoming demagnetised. Laminated 'iron' (actually silicon steel) is a 'soft' magnetic material. It's easy to magnetise with a coil of wire, but the magnetism is not retained. When the current in the coil stops flowing, the material falls back to (almost) zero magnetic field strength. This is the same type of material as used in transformers.

There's a vast amount of information available about motors. This article is intended as a primer, as it would be impossible to describe every application and variation. There are many specialised motor types that aren't particularly common (homopolar motors are just one example - look it up, because they aren't covered here, and nor are they very useful). I won't discuss 'ball-bearing' motors either - while certainly interesting they appear to have no practical use, and there's some debate over how they (barely) function. Another type not covered is the piezo motor, which uses piezo crystals to create rotary or linear motion. These are highly specialised and are usually very expensive.

While you can be excused for thinking that these motors are 'old hat' and rarely used any more, nothing could be further from the truth. They are still made (and used) in the millions each year, because they are one of the most economical motors around. You can buy them from many specialist suppliers, or find them on eBay. The most common types range from a few hundred milliwatts or so up to 500W (continuous), but there are others that operate at much lower and higher powers. Most are permanent magnet types, so they can be used as a motor or a generator. The brushes are always a cause for some concern, as they wear out from constant friction as they press onto the commutator. Brushes are typically carbon/ graphite, often with fine granules of copper to reduce resistance. In 'better' motors, they can be replaced without having to dismantle the motor. Speed control is easy, but speed regulation is not. Without a feedback system, the motor's speed is highly dependent on the applied load. As the supply voltage is reduced, torque is also reduced (though not necessarily in proportion).

These motors are also common in 'linear actuators', used for locking/ unlocking car doors, in robotics and industrial processes. The motor shaft (which may include gearing) is attached to a pinion which drives a rack (a flat or linear gear). As the motor rotates, the rack is moved in the desired direction. Most have limited travel (although up to 1 metre isn't uncommon), and there's a requirement to use limit switches to stop the motor at each end of the actuator's travel. Without that, the motor would remain powered but stalled, leading to failure. Current sensing can be used instead of limit switches, and that means power to the motor will be turned off if the rack is obstructed, jammed or overloaded.

Figure 1.1 - DC Brushed Motor Construction

The basics are shown above. The commutator switches the voltage from one winding to the next as the motor spins, ensuring that the rotor's magnetic poles are constantly changing to force the rotor to rotate. The position of the commutator segments in relation to the rotor windings is critical to obtaining the best speed and efficiency. You'll see many drawings that show a 2-pole rotor, but in all but a very few cases, the rotor will have a minimum of three poles. This ensures that it will always turn when voltage is applied. The direction of rotation can be changed simply by reversing the supply polarity. These motors can be designed for extremely high speed, with some rated for 20,000 RPM or more. Precision motors may use an 'ironless' rotor, with the windings being self-supporting. Some also use 'precious metal' brushes and commutators for greater life and lower friction losses.

For hobby motors used for model planes, boats, helicopters etc., you'll often see the speed rating in 'KV' - this doesn't mean anything at first, but it's in thousands of RPM ('K') per volt ('V') with no load. A 2KV motor will run at 10,000 RPM with 5V applied. The standard brushed DC motor is the mainstay of most 'hobby duty' servos (see Hobby Servos, ESCs And Tachometers). The same terminology is often used for 'brushless' DC motors (see next section).

Figure 1.2 - DC Brushed Motor Stator & Rotor

The stator and rotor are shown separated in the above photo. The ceramic ring inside the housing is the magnet, and you can see the three segments of the rotor. The commutator can also be seen, but not clearly enough to discern the three segments. You can see where the windings are terminated to the commutator. The copper windings are clearly visible. You can also see slots in the stator housing, which allow some movement of the brushes relative to the fixed poles. There is a specific point where the motor is most efficient (minimum current for a specific output torque).

Figure 1.3 - DC Brushed Motor & Brushes

The rotational speed is determined by a number of factors. One of the limiting factors is the strength of the permanent magnets - to obtain higher speed, they need to be weakened - pretty much the opposite of what you'd expect. Using strong magnets means higher torque, but lower RPM. It's very common for DC motors to have an attached gearbox, almost always geared down to reduce revs but increase torque. Many motors are sufficiently powerful that they can destroy the gearbox if the output is loaded excessively. This is especially true with gearboxes using a worm gear for reduction.

All of the early DC motors used field coils rather than permanent magnets. Very strong magnets are available now, but in the early days the only suitable material was AlNiCo (aluminium, nickel, cobalt), which as developed in the 1930s. It was then (and still is) fairly expensive, and that would have made its use in motors uneconomical. Until comparatively recently, most electric trains and trams used field coils, which could be switched (via the controller) to be either in series or parallel. A drawing of a motor using field coils is shown below. I've only shown two field coils, but many of these motors use four pole stators.

To reverse the direction of rotation, the polarity of either the field winding or the rotor (via the commutator) is reversed (but not both). Some motors are specifically designed to operate most efficiently in one direction, and reversing it can cause severe arcing at the brush/ commutator interface. Reversible motors generally use a compromise for the brush location, so realistically, neither direction is optimum. Sometimes the brushes can be adjusted (as seen in Figures 1.2 and 1.3, where the stator housing is slotted to allow optimum brush location).

Figure 1.4 - DC Brushed Motor With Field Coils

The common car/ truck starter motor uses this construction, with the field coil and rotor (via brushes) wired in series. This class of motor has very high starting torque, because the coils are low resistance, and carry up to 200A when stalled - limited only by the series resistance of the windings, brushes and wiring (including the internal resistance of the battery). This provides enormous magnetic field strength, allowing a small motor to turn over a car engine easily (via the ring-gear attached to the flywheel). If run with no load, as the speed increases, the current falls, reducing the magnetic 'pull'. This can allow the motor to reach dangerous speeds, limited only by friction. At high RPM the motor has little torque, but when first connected to a battery the motor will try to 'escape' from whatever is holding it.

The rate of acceleration and starting torque are both very high, so strong restraints are essential. Never allow a series-wound motor to keep accelerating (which it will with no load), as it's not unknown for a starter motor to reach such a speed that the rotor windings can literally detach from the rotor. This applies to most series wound motors, whose speed is inversely proportional to the load.

Series-wound motors are also used in many household appliances, especially vacuum cleaners and most mains powered power tools (saws, angle grinders, drills, etc.). These use a laminated core for the rotor and stator, and will operate equally well with AC or DC. Motors with field coils are often referred to as 'universal - AC/DC' motors (the band of the same name got the idea from a sewing machine motor - true!).

Figure 1.5 - Typical AC Brushed Motor With Series-Wound Field Coils

A typical AC/DC motor is pictured above. This is rated for 230V AC, but spins quite happily with only 15V DC. The DC resistance is only 16Ω, so the switch-on current could be up to 20A with 230V AC. The motor is only 80mm long (excluding shaft and rubber shock-mount). At 15V, the stall current is just under 1A (as expected from the resistance), and while it can be held stopped with one's fingers (holding the nut at the right-hand end), it still has a surprising amount of torque. With fan cooling, it would be capable of around 500W, and it was liberated from an old vacuum cleaner. The 'clean' air output was directed across the motor for cooling. The small blue 'thing' visible joining the brush mount to the frames is a 1nF Class-Y1 capacitor. There is another for the second brush.

Some other household machines (in particular sewing machines) may use a shunt-wound system, where the rotor and stator windings are in parallel. The parallel/ shunt connection is far less common than series, but exhibits a more constant speed with varying loads. It is often preferred if the speed has to be tightly controlled by the operator, but they don't have the same starting torque as a series wound motor. The maximum speed is also (more-or-less) fixed, because the stator's field strength remains constant.

A crude (but effective) speed regulator that used to be common was a centrifugal switch, which would open at a defined RPM, and close again when the motor speed fell a little. These were used in kitchen mixers for many years, but electronic speed control has taken over. By using a tachometer, the speed can be held constant with any load up to the motor's rated maximum. This isn't covered here other than as a basic concept (below).

A simple motor controller (DC only) is shown in PWM Dimmer/ Motor Speed Controller, and I have one (with a big MOSFET) to control a 400W motor used to power my mini-lathe. The circuit also works well as a DC dimmer for LED lighting (with direct connection to the LEDs - not those with an integral power supply). DC PWM speed controllers can obtain a feedback voltage by monitoring the motor's back-EMF when the 'power pulse' is turned off. The motor acts as a generator in these short intervals, and the voltage is proportional to RPM.

Because most DC motors are fairly high speed, it's common for them to have a gearbox (integrated or external. These can use 'conventional' gears and pinions, or may be planetary - the output shaft is in-line with the input shaft. This style of gearbox is very common in battery powered tools (especially drills). If you've never come across a planetary gearbox, I recommend a web search. They offer high gear ratios in a very compact unit, with no offset between the input and output shafts as is usually found with 'conventional' gearboxes.

Early electric trains (the big ones) used DC motors, and those used in Sydney from the 1920s up until the 1990s used a 1,500V DC supply, with a full 'set' (a complete 8-car train) demanding up to 1.6MW. These are commonly known as 'Red Rattlers', and they had a remarkably long life before they were finally all retired. Naturally, there's a fair bit of information about these (as well as early electric trains around the world). The 1.5kV DC supply was unusual at the time, as trains in many other countries used 750V DC, so would draw twice the current for the same power. 1,500V DC is now quite common, and is used by all of Sydney's 'heavy' rail cars (as opposed to 'light rail', which is basically a glorified tram).

Electric trains are a topic unto themselves, and most people who are interested will no doubt already have done extensive reading on the topic. For those who think that this is 'uninteresting' or even 'boring', if you have a technical mind, the more you read the more info you'll look for. Anything that can deliver up to 1.6MW (for a whole train) requires some pretty serious engineering! A 'starter' is shown at the end of the References section. Go on - you know you want to  .

.

The brushless DC motor is not a DC motor at all. Electronics are involved that switch the DC as the rotor turns (electronically commutated), and the voltage applied to the stator windings is AC, not DC. In the case of small motors, the electronics are enclosed within the motor housing, and this is most commonly found with 'BLDC' cooling fans (as used in computers, high power amplifiers, power supplies and the like). The motor is a reversal of the permanent magnet DC motor described above, with the rotor containing the magnets (not always used), and the field coils are stationary. Most use a hall-effect sensor to switch the DC from one set of field windings to the next.

There's another motor type that's also called a BLDC motor, but all the electronics are external. These are common for high power applications (for example in electric cars), and the motor is really an AC induction motor, despite the name. If the rotor uses magnets, the motor operates as a permanent magnet synchronous type, with the rotor speed directly related to the AC frequency used. If magnets are not used, the motor operates as a 'conventional' induction motor (see below).

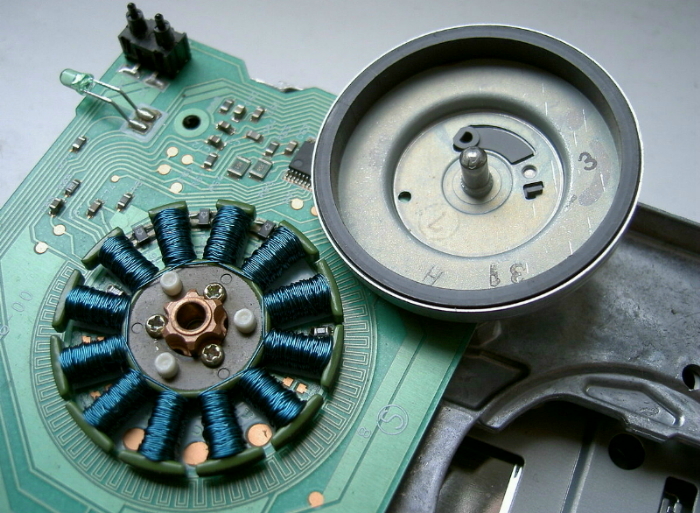

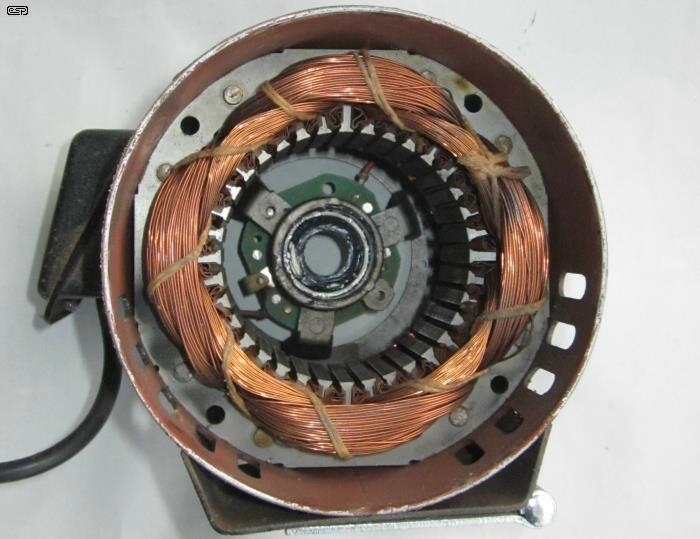

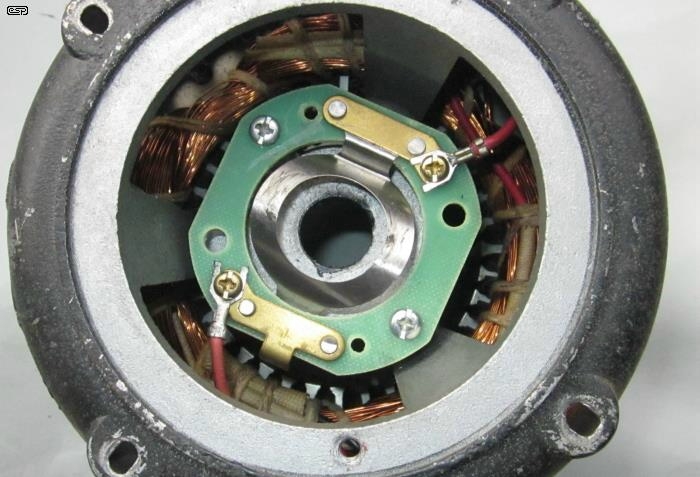

Figure 2.1 - BLDC Floppy Disc Drive Motor

( © 14 September 2007, Sebastian Koppehel (Wikipedia) Licenced )

The photo above shows a more-or-less typical small BLDC motor, as used in floppy drives (ancient technology now). The rotor is outside the stator, and is magnetised. There was no information provided about the number of poles for the rotor, but the stator has 12 poles and I'd expect the rotor to have the same. Similar motors are used for hard drives and CD/ DVD players. These motors are capable of very high speed, with high RPM types generally using fewer poles than low-speed types.

It's not particularly helpful that there are several different names used for the same type of motor. You'll see numerous acronyms, including PMM (permanent magnet motor), PMAC (permanent magnet AC), PMSM (permanent magnet synchronous motor) and BPM (brushless permanent magnet). These terms are generally interchangeable, but you always need to check the specifications carefully so the correct controller is selected. The range of controllers is vast, and using the wrong type will almost certainly not work properly (if at all).

Almost all BLDC motors are actually synchronous motors, covered in the next section. As discussed above, many use Hall-effect sensors (or sensing coils in early examples) to detect the rotor position so that the next set of coils can be energised, so they are not really synchronous, because their drive frequency and speed can vary, and the sensors determine the frequency and RPM. The maximum RPM depends on the load. These simple motors can be slowed by reducing the supply voltage (making fans quieter), but there's a lower limit. Below that, the motor may run, but can't start from rest.

Figure 2.2 - BLDC Fan Motor

A common BLDC fan motor is shown disassembled above. The blades have been removed. The rotor (left of photo) has four poles (i.e. two North, Two South), as does the stator, which uses a laminated 'iron' core and appears to be wound as 2-phase. The windings are not symmetrical, with a reading of 16 ohms across the full winding, and 8 ohms from each winding to 'common'.

The Hall sensor can just be seen between the two upper poles (at the top of the stator assembly). The controller IC is on the other side of the PCB. Like the floppy drive motor, this is an 'outer-rotor' motor, so the rotor spins and the stator (with the windings and electronics) remains stationary.

These used to be very common, with small types used in electric clocks. They were (and still are) very accurate, because the power companies worldwide need to keep the frequency (50 or 60Hz) tightly controlled so that generating capacity can be increased as needed. It's well outside the scope of this article to go into detail, but AC synchronous clocks are extremely accurate over the long term. The power company will generally ensure that the number of cycles of AC produced per day is consistent (4.32 million cycles for 50Hz mains, 5.184 million cycles for 60Hz). The first mains powered synchronous electric clock was developed in 1916 by Henry Warren (see Clock Motors for details), and many others followed as power companies worldwide ensured frequency accuracy.

In general, synchronous motors are not inherently self-starting. Many will operate as an induction motor when power is applied, and will only lock to the incoming frequency when the motor's actual speed is close to the synchronous speed. As a result, most have to be started with relatively light loading, and the load applied only once the motor has synchronised. Once the rotor has 'locked' to the AC input frequency and the load is applied, there is usually an offset between the magnetic poles. Overloading will 'break' the magnetic bond, and the motor may stop.

Figure 3.1 - Synchronous Clock Motor

An example is shown above. This motor has multiple poles, and spins slowly. The use of 24 poles was fairly common, resulting in a motor that spins at 250 RPM (50Hz). The original Warren Telechron motor was a shaded-pole type, and with only two poles ran at 3,000 RPM (50Hz) or 3,600 RPM (60Hz). The speed of a synchronous motor is determined by ...

RPM = ( f × 60 ) / ( n / 2 ) (where f is mains frequency in Hertz, and n is the number of poles)

The only way to adapt a 60Hz clock to 50Hz (or vice versa) is to change the gearing - the speed is fixed by the mains frequency. The article Frequency Changer for Low Voltage Synchronous Clocks shows how you can change from 50Hz to 60Hz or vice versa, while maintaining the accuracy of the incoming mains. For what it's worth, I have a couple of synchronous clocks, and their timing is far better than any quartz clock I own. One disadvantage of these simple multi-pole motors is that they may start in either direction, so a simple mechanical pawl is used that 'bounces' the motor to run in the correct direction. Some earlier types used a little knob that had to be spun by the user when the power was applied. These types did not re-start if the mains supply failed.

Very small synchronous motors are used in electromechanical timers (as used for turning lights and other gizmos on and off at pre-determined times). There's a photo of one in the Clock Motors article if you'd like to see an example. Notably, quartz clocks (and watches) use a similar type of motor, and they are truly tiny (especially for watches!). While these share some characteristics of synchronous motors, they operate very differently.

Many years ago, Elac (in Germany) made (vinyl disc) turntables that were unusual, in that they were both high-quality, and had the facility for record changing. Most other 'record changers' of the day used a shaded pole motor (see next section) and were generally mediocre at best. Record-changing with accurate speed required a fairly powerful synchronous motor, and the ones used were known as 'outer-rotor motors', made by Papst (now EBMPapst, which still makes motors, but not the same). With the large rotor on the outside, it acted as an effective flywheel. I used one for some years back in the early 1970s, and I have one in my workshop to this day. Many models (especially aircraft) use the same principle for high-speed BLDC motors, where they are commonly known as 'out-runners'. The floppy-disc motor shown in Figure 2.1 is an outer-rotor motor.

Small synchronous motors are very common in 'high-end' turntables to this day. Some are low voltage and use an oscillator (which provides speed changes and allows variable speed). The output is amplified and fed to the motor windings. These always use two windings, with the voltage to one shifted by 90° (quadrature) so that the motor always spins in the right direction. Others run directly from the mains, with one winding fed via a capacitor to get the required phase shift to ensure reliable starting and good torque characteristics. They can use a crystal locked oscillator for accurate fixed speeds (45 and 33⅓ RPM). Most 'direct drive' turntables use a multi-pole synchronous motor that requires no belts or gearing. The motor itself spins at the desired speed, and by careful attention to the waveform they are almost vibration-free. There are several different styles used, some being similar to any other 'outer-rotor' motor, and others using a 'pancake' (flat rotor and stator) design.

Pancake motors don't get a section of their own, because they are no different from more traditional designs in the way they work. The motor shown in Figure 2.1 can be considered a pancake design, as it's very flat (as the name implies). They are available in multiple different formats and sizes, and some are even brushed DC motors. There is a wide range of available power levels, from a couple of watts up to 6kW or more in some cases.

A few readers will know the original Hammond organs, which used 'tone wheels' to generate the notes and their harmonics. These used a synchronous motor, so the instrument was as accurate as the mains frequency. Unlike later (fully electronic but not crystal controlled) oscillators, the Hammond organ was never out of tune, and everyone else in the band had to tune their instruments to the organ. These were made from 1935 until 1975, and are still sought after (and expensive) instruments. The sound is quite distinctive, although it can be matched using modern electronics. Sadly, the synchronous motor is no longer used.

Many industrial processes use synchronous motors, which can range from fractional horsepower types up to several thousand HP (1HP is 746 watts). Once they get above a certain size, many large motors use an electromagnet for the rotor, with DC power applied via slip-rings. These are solid copper rings, insulated from the drive shaft, and power is delivered with brushes. Wear is minimal, because there are no gaps in a slip-ring. I once worked on a 1,000HP (746kW) synchronous motor, helping to ensure that it was properly balanced as it was to be used in a water supply pumping station (27/7 operation). That was one scary machine when it got up to speed, as much of its 'innards' were exposed for all to see (but definitely not touch !).

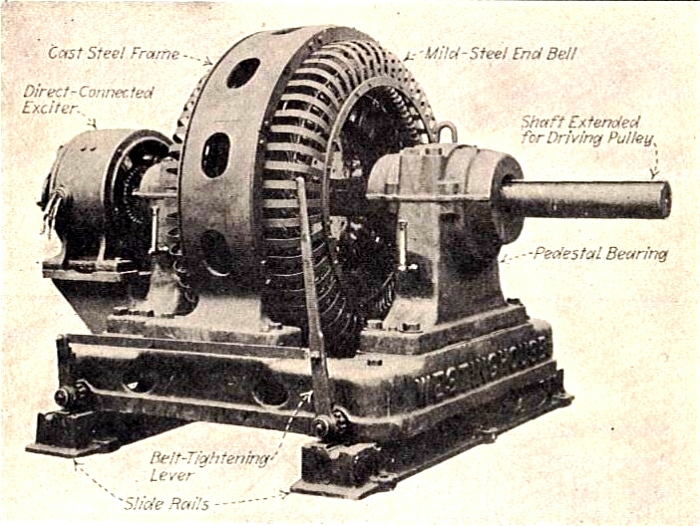

Figure 3.2 - Westinghouse 'Type C' Synchronous Motor With Direct-Connected Exciter (Wikipedia)

The motor shown above dates from 1917 and is not too dissimilar from the one I worked on (although it was somewhat less ancient). The 'exciter' shown is a DC generator used to magnetise the rotor, and by having it directly mounted to the drive shaft means that slip-rings aren't needed. However, the generator requires a commutator to 'rectify' the AC output from the exciter's rotor winding, which means that it's hardly maintenance-free.

An interesting use for synchronous motors is for power factor correction. The motor is (usually) run with no load, and the power factor can be changed by altering the DC excitation current. When the excitation current is lower than 'normal' the motor has a lagging power factor (inductive), and if excitation current is increased past the critical point, the power factor is leading (capacitive). Note that this only works when the mains current is linear, but out of phase (see Power Factor - The Reality (Or What Is Power Factor And Why Is It Important) for information on power factor). Many modern loads draw a non-linear current from the mains, and this cannot be corrected with a synchronous motor (or a capacitor bank).

Shaded pole motors are one of the most common small AC types available. Unlike 'traditional' single-phase induction motors, they don't require any starting system, but they are limited to low power application. You'll commonly find them in desk, pedestal and exhaust fans, end they are also used as pumping motors for washing machines and dishwashers. Most will be rated for no more than around 50W (0.67HP), although there are a few used at higher power (up to 150W is available, but fairly uncommon). These higher powered versions will often be rated for intermittent use only, unless a cooling fan is attached to the output shaft. These motors are not very efficient, and have low power factor and don't run happily if loaded when power is applied, due to very low starting torque.

A variation on the standard shaded-pole motor is the shaded-pole synchronous motor. The rotor is magnetised, and will rotate at the AC synchronous speed (3,000 RPM for 50Hz, 3,600 RPM for 60Hz). These were once common for AC electric clocks, with one of the earliest being made by the Warren Clock Company of Ashland, MA (patent #1,283,431 applied for on 21 Aug 1916 and granted 29 Oct 1918). See Clock Motors & How They Work. These synchronous shaded-pole motors have very low torque. Most shaded-pole motors in use today are not synchronous, and are used for fans (desk, ceiling or pedestal). They are gradually being replaced by BLDC motors for 'high end' products (see Section 2 [above] for details).

Synchronous shaded-pole motors were also sometimes used for vinyl turntables. These were used with some of the 'better' record-changers, and were fairly robust. The motor could drop out of synchronous operation during a record change (due to relatively high loading) but would return to synchronous operation once that process was complete. Several manufacturers used these motors in the 1960s and 1970s, but the desire for 'better' speed regulation and the demise of the record-changer spelled the end for them in this role.

Figure 4.1 - Shaded Pole Motor

The 'shaded' poles have a short-circuit ring around them, which forces the flux in the shaded pole to be shifted with respect to the 'main' poles. In the arrangement shown, the motor will spin clockwise. It can be reversed only by removing the bearing plates and installing the rotor the other way around (with the shaft pointing up in the top view). This is a trick worth knowing if you have one of these motors but need it to spin the other way from 'normal'. Like all squirrel-cage motors, the rotor has embedded conductors, which are typically die-cast aluminium.

The efficiency of these motors is low, rarely better than 50%. This is due to power losses in the laminated steel core, additional losses due to the shaded poles, and losses in the rotor itself. They also have very poor power factor, as evidenced by measurements of the motor shown next.

Figure 4.2A - Shaded Pole Motor With Gearbox

Those who know shaded pole motors already will tend to think of them as being (usually) pretty small and wimpy. The photo shown proves that this isn't always the case. I don't recall what it's from, but it has a very substantial core, and is fitted with a 3-stage gearbox to reduce speed and increase torque. Most motors have the power rating and output speed on the nameplate, but that's missing on this one. It only states that it's for 220-240V, 50 or 60Hz. I did manage to track down a datasheet, but that is not as helpful as one would hope. I measured it, and it pulls 1.5A at 230V and dissipates 100W (Power factor is very poor - less than 0.3). Output speed is about 16 RPM, and there was no way I could stop it when hand-held. Output torque is very high!

Figure 4.2B - Shaded Pole Motor End View

From the end, you can (almost) see the rotor, with the shaft and bearing more visible. I know it's not an exciting view, but it's included so the 'real thing' can be compared to the drawing in Figure 4.1. The vast majority of these motors are small and wimpy, so it's at least a bit interesting to see one that's designed for some fairly serious torque. Unfortunately (and to add to its unusual nature), the output shaft has a left-hand thread, and I don't have a nut that will fit it. Now, if I could only recall from whence I got it ...

Of all motors, these are the most common. Shaded pole motors as described above are still induction motors, and the principles are virtually identical, except that shaded pole motors don't need a start winding. Nicola Tesla is credited with the invention of the induction motor, and they have been in use for over a century. These motors are used in countless industrial processes, and are the mainstay of power tools such as drill-presses, bench grinders/ belt sanders, radial-arm saws, band-saws, lathes and many others. Fractional horsepower types are common for small workshops, with ratings between 1/4HP and 1/3HP (180 - 250W). These are almost invariably single-phase, and all single-phase motors require a starting mechanism.

The contacts for the centrifugal switch are normally closed, and as the motor comes up to speed, the weights pull back the actuator and the switch opens. This ensures minimal friction when the motor is running, and prevents wear on the actuator and contact assembly. The contacts are usually only closed for a fraction of a second after power is applied, but this depends on the load. Where a high starting torque is necessary, capacitor-start is preferable to resistance-start systems.

Figure 5.1 - Single-Phase Induction Motor Internals

The general idea is shown above. These are very simple machines, which helps to ensure that they can last for 50 years or more without any attention whatsoever. I know this because I have one that's at least 60 years old, and it still works perfectly. It powers a medium-sized drill-press, and it doesn't get a great deal of use, but that's a very long time for anything to remain serviceable without a single repair! Note that the drawing doesn't try very hard to show the workings of the centrifugal actuator or the switch. These vary widely in design (and longevity), and while not particularly complex, it would be hard to to fit it into the drawing. The only way to know how the one you have (assuming that you have one) is to pull the motor apart and look at the mechanism (or you can look at the photos shown below). Not all induction motors use a fan - those intended for intermittent rating (or for dusty/ explosive conditions) are sealed, and rely on external cooling.

The stator is comprised of circular laminations, with slots for the windings. The windings are fully insulated from the stator with the winding wire enamel, plus a secondary layer of heavy duty insulation within each slot. The windings are often held in place with a piece of stiff insulation that clamps them firmly in position. Winding movement may lead to abrasive damage to the enamel insulation, resulting in motor failure. For high-reliability applications, the entire stator may be vacuum impregnated after completion. This ensures maximum reliability, but it also means that the motor cannot be economically repaired.

Both the rotor and stator cores are laminated, because they handle AC. The stator is connected to the AC supply, and AC is induced into the (usually) aluminium conductors that are cast into the rotor. These conductors act as shorted turns, allowing a high magnetic field strength (due to high conductor current) with very little voltage. The rotor turns slightly slower than the mains derived magnetic field, and the speed falls (and magnetic strength increases) with increasing load.

There are two different approaches used for starting single-phase induction motors, and in some cases these's also a third option. Without a start winding, the motor can be started manually, just by spinning the shaft. That this practice is potentially dangerous is without question (especially for a saw or lathe!). If an induction motor is manually started, it will spin in the direction that initiated operation (either forwards or backwards!). If nothing is done the motor will remain motionless, but will draw a very high current.

Figure 5.2A - Induction Motor Stator Assembly

The stator is shown above, and the windings and stator winding slots can be seen. Also visible is the rear bearing cup and the rear of the centrifugally operated switch. The 'run' windings are at the outside, and are heavier gauge (and slightly darker coloured) than the 'start' winding. The latter is disconnected by the centrifugal switch when the motor reaches about 80% of nominal speed.

Figure 5.2B - Induction Motor Rotor Assembly

The rotor shown above is typical of those used in most small induction motors. The 'stripes' you can see are aluminium conductors which are shorted at each end. This is commonly known as a 'squirrel cage' rotor, because if the laminated steel core is removed it would look like a cage, typical of those used for small animals for exercise. While the above photo shows the rotor 'windings' skewed, this is not always the case. Because the windings are shorted, current induced into them (by transformer action) is very high, and that creates a strong magnetic field.

The rotor has a fan at one end (within the end-bell), the rotor itself with the aluminium conductors and end pieces easily seen. The rotor 'shorting' end-pieces also have fins to provide some additional cooling. These are not always used, but aren't particularly uncommon. The centrifugal actuator is visible on the right-hand end of the shaft.

Figure 5.2C - Induction Motor Centrifugal Switch

The switch itself is very basic. It has no mechanical hysteresis, as this is provided by the actuator shown next. The wiring back to the terminal block is easily seen. The switch is normally closed, and the centrifugal actuator opens it at the designated speed. The actuator is arranged so there is no contact with the switch mechanism after it activates, so there is only a sliding contact as the motor starts and stops. A smear of grease is visible on the circular switch operating ring. This minimises wear during starting and stopping. The photo shows just one of many different configurations that are used, but the operating principles are the same.

Figure 5.2D - Induction Motor Centrifugal Actuator

The centrifugal actuator is a relatively simple affair, and is just one of many variations on the theme. At rest or below the cut-out speed, the weights are as shown in the photo. Once the motor gets up to speed, the weights are thrown outwards (so they are parallel to the pivots), and this retracts the black plastic plunger which disengages the start winding. The weights and springs have to be tailored for the motor's nominal full load speed, in this case 1,400 RPM. The switch will activate at around 1,100 RPM, but it's not a high precision device and there will always be some variation.

The rotor's magnetic field interacts with the stator's magnetic field to cause the rotor to spin - using the start winding for single-phase motors. The start winding can either be resistive (commonly referred to as a 'split-phase' motor as seen in Figure 5.2A) or it can use a capacitor. With capacitor-start motors, some use capacitance only to start, and others have a large start capacitor that's switched out with a centrifugal switch, and a smaller 'run' capacitor. These generally have higher torque than split-phase motors.

Note that 3-Phase motors have an inherently rotating magnetic field, and a start winding is not required. Starting current mitigation is essential with very large motors.

As the motor comes up to speed, the flux in the rotor reduces, because it approaches the synchronous speed dictated by the frequency and number of poles. When a load is applied, the rotor slows down, causing more current in the rotor 'windings' and increasing their magnetic field strength. This is known as 'slip', and all asynchronous induction motors use the slip to try to maintain speed. A 4-pole motor at 50Hz has a synchronous speed of 1,500 RPM, but the rotor will typically run at around 1,400 RPM at full load (7% slip). Larger motors generally have less slip than small ones [ 4 ]. If the motor is loaded too heavily, it will lose torque rapidly and will draw excessive current.

The cheapest (and most cost-effective due to the vast numbers made) is a 'resistance-start' system (aka 'split-phase'). The main winding is supplemented by a secondary winding with comparatively high resistance. When the motor is started, the two windings are connected to the mains supply. The main winding has a poor power factor at this point, so the winding current lags (is behind) the voltage. The resistive winding has a much better power factor due to its resistance, with voltage and current closer to being in-phase. The interaction of the two creates a rotating magnetic field that causes the rotor to accelerate. At about 80% of the rated RPM, a centrifugal switch disconnects the resistance winding, which would otherwise overheat and cause the motor to 'burn out'. The motor is then able to keep turning by itself - once running, the start winding is no longer needed.

A capacitor-start motor also uses a secondary winding, but it can be a lower resistance. The secondary winding is then supplied via a capacitor, which creates a leading power factor (the current occurs before the voltage). (While this may seem unlikely, it is a well proven technique.) Like the resistance winding, the capacitor-fed winding interacts with the main winding to create a rotating magnetic field, and the motor starts.

In capacitor-start motors, a centrifugal switch is again used to disconnect the start winding when the motor is nearly up to speed. Some other motors keep the capacitor in circuit (capacitor run operation), which improves torque. The capacitor value is selected to produce a phase difference of 90° (or as close as possible) for both types. A few capacitor start motors use a fixed (run) capacitor and a start capacitor, to improve both starting and running torque.

Figure 5.3 - Capacitor Start Induction Motor

Some small synchronous motors (particularly those used for vinyl turntables) often use two identical windings, and a capacitor is connected to one or the other. This allows the motor to be reversed simply by reversing the connections. See the drawing below that shows how the capacitor can be connected. This also works with asynchronous (induction) motors, but only if the two windings are identical, and is generally limited to relatively low-power motors. Direction reversal is provided by reversing the polarity of the start winding or the main winding. (This also applies to split-phase motors with a resistive start winding.)

Figure 5.4 - Reversible Capacitor Start Synchronous/ Asynchronous Motor

In some cases, a current-activated relay is used instead of the centrifugal switch (mainly for smaller motors and comparatively uncommon). The high starting current causes the relay to pull in and connect the start winding, and as it falls when the motor approaches operating speed, there's not enough current to hold the relay closed, so it disconnects the start winding. These are uncommon - I know of their existence, but have never come across one. I worked on a lot of motors in my early 20s (now that was a long time ago), but not so many in later years.

Larger motors (typically those of 2 - 3HP (1.5 - 2.3kW) and above) are almost always 'poly-phase' - generally 3-phase types. While a single-phase motor can be up to around 5HP (3.72kW), the start current is too high to allow them to connect to a wall outlet without overload. 3-Phase motors use a higher voltage (400V in Australia and most of Europe, but may be different elsewhere), so require less current for the same power output.

Speed control of single phase motors is difficult because of the centrifugal switch. If the motor is slowed to the point where the switch engages the start winding, it will almost certainly fail due to overheating. With capacitor run motors (where the capacitor is permanently connected), the fixed capacitance means that at lower speeds it's less effective. As a result, most single phase motors use either stepped pulleys or a gearbox to change speeds. Stepped pulleys are very common with small bench drill-presses and the like, and some use an intermediate idler pulley to provide more speed options.

Changing the belt to different pulley sizes is a nuisance, but it works well enough in practice, and the technique is almost as old as the idea of a drill press itself. All modern units use V-belts, which can transmit significant torque if properly tensioned. The same system is used with some small milling machines, along with many other machines where different speeds are required.

In some cases a variable frequency drive (see 3-Phase Speed Control below for details) can be used with single-phase motors that are specifically designed for use in this application. Most are not, so it's not something that can be applied without a great deal of research. Attempting to use any motor in a configuration for which it was not designed can often lead to unexpected failure. As is to be expected, a single-phase motor with a centrifugal switch cannot be used with any form of speed controller. At low speed, the centrifugal switch will close, engaging the start winding (whether resistive or capacitive). The will lead to rapid overheating and failure.

The only motors that can use variable frequency are 'permanent split capacitor' (PSC), shaded pole and synchronous motors (the latter are very uncommon in all but the most esoteric applications). One of the very few can be found in some vinyl turntables, although the majority use a PSC synchronous configuration.

I don't intend to spend much time on 3-phase motors, because the majority of people will never come across on (other than small 3-phase 'BLDC' hobby-motors). Very large motors require special care when starting, mainly because they are very large, and they draw an astonishing amount of current when started. Back when I worked on such motors, the most common arrangement was a slip-ring 3-phase motor, usually running from at least 415V (now nominally 400V) 3-phase power, although once over 500HP (373kW, or 300A/ phase) higher voltages were used (such as 1.1kV). These motors used a 'resistance-start' arrangement, where the rotor has windings that are connected to slip-rings [ 3 ]. When power is applied, the slip-rings are connected to very high power resistors (typically made from a specialised cast-iron alloy). As the motor speed increases, the resistance is reduced using high-current contactors (very large relays), until once full speed is reached, the slip-rings are shorted and the motor runs as a 'normal' induction motor.

Figure 7.1 - 3-Phase Voltage Waveform

The 3-phase waveform consists of three sinewaves, with 120° displacement between each. This inherently creates a rotating magnetic field when applied to a 3-phase motor. Direction can be reversed by swapping any two phases. They have been shown as Phase 1, 2 and 3 above, but are also known as 'A, B and C', or by the colours used (which varies between countries). The graphs show three 230V sinewaves at 50Hz, and this needs to be changed to suit other voltages and frequencies. The voltage for each phase with respect to neutral (see Figure 7.2) is 230V RMS, and the voltage between any two phases is (nominally) 400V RMS. You can calculate the 3-phase voltage by multiplying the single-phase voltage by the square root of three (√3).

230 × √3 = 2 × 1.732 = 398V

Small 3-phase motors (up to perhaps 50HP (37kW)) use a start system known as 'star-delta' or 'Wye-delta' (Y-Δ). Now, consider a 40HP motor (30kW), connected to a 415V 3-phase supply. Full load current is 26.7A per phase. Because the starting current of a delta connected motor is around 6 × the running current, the motor will pull around 160A per phase if connected directly to the supply (known as 'DOL' or direct on-line starting). This is usually quite unacceptable, so for starting, the motor is connected as 'star' or 'Wye'. This reduces the maximum starting current to about 90A - still very high, but tolerable in an industrial setting. Once up to speed, the windings are reconfigured with a switch or contactor into the delta pattern, which gives maximum power.

The overall construction of a 3-phase motor is very similar to a single phase type, except there are three windings, and no centrifugal switch.

While most people seem to think that motors have a very poor power factor (PF), that's only true if they are lightly loaded. At full rated power, you can expect the PF to be at least 0.85. That represents a phase angle of about 60° lagging (due to inductance). Bigger motors are engineered to have a higher power factor, as that reduces the reactive current drawn from the mains supply.

Figure 7.2 - Star (Wye) And Delta (Δ) Motor Windings

The above shows the two winding types. Many people who work with 'BLDC' hobby motors (which aren't restricted to hobbies!) will recognise the winding pattern, and the ESC (electronic speed controller) for these motors outputs a 3-phase AC signal that powers the motor. These motors are almost invariably connected in delta. A neutral isn't provided, and it's not needed.

Variable frequency drives (VFDs) are now very common, and provide a 3-phase output that has both frequency and amplitude control. The motor's speed is varied by changing the frequency, and the amplitude is changed to maintain a reasonably constant power in the motor windings. As the frequency is reduced, the current would normally rise because the inductance remains constant. At some frequency (not much below the normal operating frequency of 50-60Hz) the stator core will start to saturate, causing a rapid increase of current and failure of the motor, VFD or both. To combat this, the VFD reduces the voltage when the frequency is reduced, and vice versa. There is always a lower and upper limit, and trying to use the motor 'inappropriately' will cause failure. The following relationships are important when using speed control ...

Magnetic strength (or Magnetic Flux) is proportional to Voltage and frequency

Torque is directly related to magnetic strength

Power (kW) = torque (Nm) × ω (where ω = 2π × RPM / 60)

When a motor's output speed is reduced with gearing or belt drives, the torque is increased in inverse proportion to the speed reduction. For example, if the speed is reduced to half, the torque is doubled, and the power remains constant. This is not the case when a VFD is used. If the speed is reduced to half by reducing the frequency from 50Hz to 25Hz, the torque remains the same, so power is also halved. Variable speed is useful to ensure the machine runs at a speed that's appropriate for the job, but the power varies with the frequency applied.

There are other complications as well, especially if the power frequency is much higher than normal because you want the motor to operate at a speed greater than it was designed for. Voltages may exceed the insulation rating, eddy current losses will be higher than expected, and even bearings can be damaged (either through excessive speed or electrolytic corrosion). VFDs use PWM (pulse width modulation) to create the output waveform, and this usually contains harmonic frequencies that are much higher than the frequency delivered. It's usually recommended that the output shaft should be earthed/ grounded with a specially designed 'grounding ring' to prevent current induced into the rotor from passing through the bearing itself when a VFD is used.

At first glance, using a VFD seems simple enough, but if all precautions aren't followed motor damage is very likely. These issues are well outside the scope of this article, but there is plenty of information (and warnings) from various manufacturers, and elsewhere on the Net. If this is something you are planning to use (or already use), it's worthwhile to read up on bearing damage, as it's a common problem that isn't always addressed properly.

Stepper motors (aka stepping motors) are used in so many things that it would be impossible to list them all. A few examples include computer printers and scanners, 3D printers, CNC (computer numerically controlled) machines of most types, robots (both toy and 'real') and for all manner of positioning applications. They are commonly used 'open-loop', and there is no feedback mechanism used. Stepper motors can be used as fast as the design will allow or down to DC, with no change to torque or holding power (when stopped). The same relationship to power applies as it does with variable speed induction motors.

Provided the load is well within the limits of the motor, it can be relied upon to perform exactly the number of rotations (or part thereof) that's programmed into the controller. This is why ink-jet printers (for example) move the print head from one extreme to the other when turned on. The 'home' position is established, and the printer knows exactly how many rotor turns are needed fo move the head to the end position. If the print-head is jammed, the limit switch won't be activated after the programmed number of turns, and an error light will come on. Similar tests are performed by scanners and other equipment controlled by stepper motors.

The simplest stepper motor of all is used in common quartz clocks. These are a 'special' case, because the rotor turns 180° with each alternating pulse. The winding is clearly visible in the photo, and the rotor is beneath the small gear seen between the two metal 'arms'. These are carefully shaped to ensure that the rotor always turns in the proper direction.

Figure 9.1 - Quartz Clock Motor

Stepper motors are characterised by type and size. The ones that are the most common are a hybrid, being a combination of variable-reluctance and permanent-magnet types.

'Proper' stepper motors have a tightly controlled and precise angle between full steps, typically 1.8°. That means the motor requires 200 steps to complete one revolution. Specialised driver ICs provide half-step and 'micro-step' capabilities, by controlling the winding current. While a stepper motor is (in theory) a synchronous poly-phase motor, it is the ability to be used at any desired frequency up to the maximum - the upper limit is determined by the coil inductance. With the capability to be locked at any position, it is sufficiently different from a synchronous motor that (IMO) equating the two is folly. The photo below shows the intestines of a NEMA-17 stepper motor.

Figure 9.2 - NEMA-17 Stepper Motor Dismantled

The 'teeth' on both the rotor and stator provide the key to operation. When a pair of windings is energised, the rotor will move and lock to that position, and it takes some effort to move it as long as current is applied. By switching current from one set of windings to the next, the motor will rotate by one 'step' (1.8°). If both windings are energised, the motor will move by one half step (0.9°). there are several different ways that a stepper motor can be wired, depending on the motor itself. The most common variants are uni-polar and bi-polar. A bipolar motor usually only has two pairs of wires, while uni-polar types usually have six (but sometimes five or eight) wires. There are two separate windings in these, each with a centre-tap.

Figure 9.3 - Uni-Polar And Bi-Polar Motor Wiring

As should be expected, a uni-polar motor with a DC voltage on the common (centre-tap) leads only needs the drive wires to be grounded to obtain current flow. A bi-polar motor requires that the polarity to each coil is reversed for alternating pulses (the quartz clock stepper motor is bi-polar). The dismantled motor shown in Figure 9.2 is uni-polar, and the full winding measures 6.2Ω (3.1Ω for each winding from centre-tap). Uni-polar motors can be used as bi-polar by ignoring the centre-tap, but a uni-polar motor cannot be wired for bi-polar operation.

Figure 9.4 - A Selection Of Different Stepper Motors

Owner: Bill Earl, License: Attribution-ShareAlike Creative Commons

As you can see from the above, there are many different types and styles of stepper motors. While not shown in the above, there are also some very large ones - I have on in my workshop that's over 200mm long and 150mm diameter. If the windings are shorted, it requires a pair of strong 'multigrip' pliers or similar to just move the shaft. This is one of the attractions of stepper motors in general. If the static load is small, just shorting the windings will keep the motor from turning, but even with a fairly high load, even a small current can be enough to prevent the motor from turning. The preset position is maintained, without any requirement for a servo system to make it stay where you want it.

Figure 9.5 - Uni-Polar Stepper Motor Logic

Each logic output connects to a high-current switch (e.g. a MOSFET), shorting the relevant winding to ground. The is only one of many ways to driver stepper motors, and it's been shown because it's easily simulated and can be built using cheap CMOS parts (using a 12V supply) and driving output MOSFETs. The direction is reversed by pulling the 'Dir' input high. The clock signal is nominally a squarewave, and can be as slow as you like. The devices specified are a 4584 (hex Schmitt inverter), 4070 (dual XOR gate) and 4013 (dual D-Type flip-flop). Note that there are two coils energised at any point in time, providing the maximum possible torque.

The maximum clock speed is determined by the winding inductance and available voltage. A common way to get higher than 'normal' speed is to use a higher voltage supply (e.g. 12V for a 5V motor) and use current-limiting so the motor doesn't draw excessive current and overheat. This can be active (using transistors) or passive (using resistors). More advanced control systems are IC based, and provide many advantages over the simple scheme shown, but may only be available in an SMD package, and may require a microcontroller to function.

Paradoxically perhaps, bipolar motors are simpler than unipolar types, but are harder to drive. Instead of simple MOSFET switches for each winding-end (four in all) you need eight MOSFETs (or bipolar transistors), and a more complex drive circuit. The switching devices are wired as an H-bridge, and a minimum of four devices are required for each winding. With MOSFETs, they'll usually be N-Channel and P-Channel types (NPN and PNP for BJTs).

Figure 9.6 - Bi-Polar Stepper Motor H-Bridge

The drawing above is a somewhat unusual H-Bridge driver circuit, that only requires a pair of drive signals. The required switching is performed by the resistors (R3, R6), which are cross connected so that when Q1 turns on, it forces Q4 to turn on as well. When Q3 is turned on, that turns on Q2. It's important that both drive signals are never present at the same time, as that would cause all MOSFETs to turn on, shorting the supply. A small 'dead-band' (where all MOSFETs are off) is required, but it only needs to be about 20µs - just long enough to ensure that the MOSFETs are off before the second pair is energised. This is no different from the arrangement used for Class-D power amplifiers, and all H-Bridge circuits have the same requirement for a dead-band. The zener diodes protect the MOSFET gates from voltage spikes that may cause failure. I do not consider them as 'optional', although many circuits you'll see don't include them.

With MOSFETs, there is no real requirement for additional diodes, because they are intrinsic to the MOSFET (the internal 'body' diode). These aren't usually especially fast, but stepper motors cannot accept high-speed input frequencies anyway, and it's not usually a problem. External diodes can be added, but are usually only required when the output switches are bipolar transistors.

The circuit is shown with values to suit 12V motors, or a lower voltage motor with a series resistor. Higher voltages are easily accommodated by increasing the value of R3 and R6. For example, if you have a 24V motor, these resistors are increased to 1k, so the upper MOSFETs still get a 12V gate voltage. It can also be used with lower voltages, but the MOSFETs must be low-threshold types, with a gate turn-on voltage suitable for the voltage used. The minimum will normally be around 5V, and suitable MOSFETs are available (although the choice of P-Channel devices is limited). The scheme shown is simpler than most, with many expecting four separate control voltages, all of which must be synchronised without overlap that can cause cross-conduction (two MOSFETs in the same 'stack' turned on at the same time).

Figure 9.7 - Alternative Bi-Polar Stepper Motor H-Bridge

A common arrangement is to use the MOSFETs with their gates simply tied together (optionally with gate resistors and diodes) as shown above. This scheme demands that the drive voltage and supply voltage are the same, and it cannot be higher than the maximum gate voltage. This may not be ideal for the application, and while it certainly will work, it lacks any flexibility in the selection of the motor. Admittedly, most stepper motors are designed for low voltage operation, but a circuit that imposes arbitrary limits is ... limiting.

Of course, you can always cheat and use a power H-Bridge IC such as the L298 (BJT output switches). This has the switching and basic logic all sorted out for you, but it's not necessarily ideal. It does have logic circuitry that steers the output transistor drive current and ensures that there is minimal 'shoot-through' current (it includes the required dead-band). Unlike MOSFET switches, there are no parallel diodes to protect from voltage spikes, and these must be high speed types, added externally (eight diodes for a bipolar stepper motor).

Linear motors can be thought of as a 'conventional' motor that's been 'unrolled'. They are surprisingly common, though mostly you won't know they are there [ 5 ]. There are many considerations, not the least of which is maintaining the correct (and generally very small) distance between the stator and the propulsion system. They are common in 'MagLev' (magnetic levitation) systems for trains. See the Wikipedia page referenced for more information.

Like many other more advanced topics, a full discussion of linear motors is (well) outside the scope of this article. They are mentioned here purely because they exist, and are in use in many parts of the world. A web search will provide you with plenty of reading material, but it's not something that most hobbyists will get into. So-called 'rail guns' use a form of linear motor as well, and these have been built by hobbyists and professionals alike. Other than pointing out that they exist, I don't propose to go into more detail here.

A very basic introduction to speed control was provided in Section 6, related to the use of a VFD unit, but with induction and DC motors the speed stability can be highly variable. In some cases, it's (perhaps surprisingly) an advantage if the motor slows under heavy load. When loaded the motor slows, giving the operator more time to negotiate tricky parts - this is especially true of sewing machines! No-one (unless very experienced) wants the machine to sew at high speed over heavy seams, so allowing the motor to slow down helps the user to negotiate problem areas more easily. However, this is certainly not desirable for many other applications.

Synchronous motor speed is determined by only one thing - the AC input frequency. Stepper motor speed is determined by the pulse rate - provided it's lower than the maximum allowable of course. When DC or induction motors are operated 'open loop' (with no form of feedback), the speed will vary, and dramatically so with DC motors. Feedback involves providing a means of monitoring the actual shaft speed, which can then be compared to the 'reference' setting. This allows the system to automatically adjust the motor power as the load changes.

The monitoring device can be a small motor operated as a generator, a digital encoder that provides both speed and direction information, or simpler units can monitor the current drawn and make corrections based on how much current the motor is drawing. The latter are not precision speed regulators, but they can suffice in non-demanding applications.

However, accurate speed control/ regulation is not trivial! Because a motor has inertia and momentum (determined by the mass of the rotor and the coupled load), this introduces a mechanical 'filter' into the equation that makes a stable feedback system difficult to design. This is one reason that 'ironless' or 'coreless' motors are popular in high speed applications where the RPM needs to change quickly. With less mechanical inertia, acceleration and deceleration are much faster, and it makes the controller easier to design.

It is beyond the scope of this (introductory) article to go into great detail, but a common approach is a 'PID' (proportional integral derivative) controller. These are discussed briefly in the Servos article, and there are countless PID controllers one can buy, and a great deal of info on the interwebs. If a very well regulated speed is needed, a synchronous motor is probably the best option. However, they are rarely suited for accurate positioning tasks, and there is a definite limit as to how quickly you can make speed changes (mainly due to motor inertia/ momentum).

Seeming simple tasks (like maintaining a pre-determined speed regardless of load) are nowhere near as simple as they may appear at first. Dealing with instability in purely electronic circuits is usually fairly straightforward, but the task is a great deal harder when there are mechanical forces working against you. Because many machines not only require constant speed, but are also subjected to variable load conditions makes everything that much harder.

Motors generally require balancing to prevent vibration while running. A common approach is to drill into parts of the rotor laminations to remove weight from the heavier side(s) of the rotor itself. It's generally close to impossible to wind or build a rotor that is perfectly symmetrical in every respect, and it's usually equally difficult to add weights, as there's always the possibility that they will fall off (or fly off!) or be dislodged during assembly/ disassembly. The degree of balancing needed depends on the size and speed of the motor. Large low-speed motors require careful balancing, as do small high-speed motors. The forces created are proportional to the unbalanced mass and the square of RPM. Double the speed, and the unbalance forces increase by four times.

A small imbalance may be be imperceptible at 1,500 RPM in an 'average' sized motor (fractional horsepower types), but the same magnitude of imbalance will destroy bearings with larger motors or at higher speeds. Where balancing is performed, it should ideally be a dynamic test, where the rotor is spun and computerised equipment pinpoints the exact location where weight(s) have to be added or removed. Less satisfactory (but often acceptable) is a static balance, where the part to be balanced is placed on a perfectly flat pair of knife-edge supports, or fitted with very low friction bearings. If the part always turns so a particular point faces down, then that part is obviously heavier than the rest. When (very gently) rolled on the knife-edges or rotated, a well balanced part should stop at a random position each time. This doesn't mean that the rotor is truly balanced though - there may be situations where there is equal but opposite imbalance laterally (along the length/ width of the part to be balanced.

Dynamic balancing will ensure that all sources of imbalance are identified. For anyone who's seen car wheels and tyres being balanced, you'll know that weights are added to the inside and outside of the rims, to ensure that there are no lateral forces. This is not identified with static balancing, and it's rarely used any more. Some information is available at Motor Repair Best Practices, but there's a lot more general info available if you search for 'Dynamic Balancing' (which isn't specific to electric motors).

Few (if any) hobbyists will have access to precision dynamic balancing equipment, as it tends to be rather expensive. However, it's important that not only the motor's rotor, but anything directly attached to the motor shaft is balanced as well. Failure to balance high-speed (or high rotating mass) loads will lead to bearing failure, or even complete motor destruction should a bearing fail catastrophically! It's unlikely that most hobbyists will ever need to balance a rotor, but if you're dealing with high-speed motors it's something to think about.

A good introduction to static and dynamic balance is shown at Balancing Know-How: Understanding Unbalance (YouTube). If you want (or need) more, there are many other videos on the subject. As always, be careful. Just because someone posts a video, that doesn't mean that they know what they are talking about!

This is a primer on electric motors, and as such doesn't attempt to cover every possibility. Motors are used in so many different ways that it would be impossible to list them all, and even more so to examine every control system. There is a great deal of information on-line, and most of it is accurate. Unlike audio, there is very little snake-oil in the motor industry, but some people have used motors to sell fraudulent products ('power savers' are a prime example - they are almost all based on peoples' lack of understanding).

There isn't a great deal to add here, other than to commend the interested reader to do further research for the specific type of motor s/he intends to use. While the motor as a basic 'black-box' machine is very simple, there are subtleties that can easily cause any project that relies on motors to fail. I've only shown a limited number of references below, but there are thousands of articles about motors, covering every type in use. Many include photos and drawings, along with formulae for calculating almost every aspect of their operation.

I deliberately kept the maths in this article to the bare minimum, and there are no phase diagrams or animations. These are all available if the basic concepts don't seem to help you to make sense of the operation and control of any style of motor. While very simple machines, electric motors are (like transformers), far more complex than they appear. Hopefully, this primer will help the reader to appreciate their versatility and give some insight into how they work.

Main Index

Main Index

Articles Index

Articles Index