|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 71 |

Please Note: PCBs are available for this project. Click the image for details.

Please Note: PCBs are available for this project. Click the image for details.The Linkwitz transform circuit is a hugely flexible way to equalise the bottom end of a sealed loudspeaker enclosure. Unlike the original 'EAS' (Electronically Assisted Subwoofer) project or the ELF™ systems, a speaker that is corrected using this method is flat from below resonance to the upper limit of the selected driver. The low frequency rolloff point is determined by the parameters of the transform circuit. Should the enclosure size be too small and cause a lump in the response before rolloff, this is also corrected. A conventional active crossover network is then used to divide the subwoofer signal from the main channel signals.

For a detailed look at how the circuit works, please click here to see the article that describes the operation of the circuit.

The original Linkwitz Transform spreadsheet was presented by TrueAudio [ 2 ], and is reproduced here with their permission. One of my readers added an extremely useful extra page that calculates the driver response in the box, and I added the ability to use litres instead of cubic feet if desired. The transform circuit was invented by Siegfried Linkwitz [ 1 ], and is another of his gifts to the audio world (the other is the Linkwitz-Riley crossover).

The Linkwitz Transform spreadsheet can be downloaded here, or from the Downloads page.

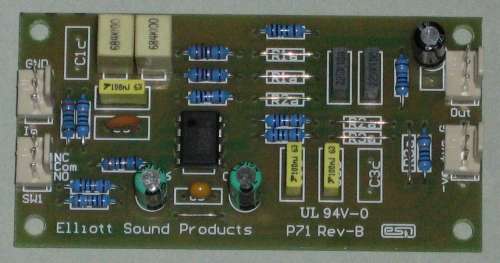

Photo of Completed P71 Board

The photo shows the completed board, which measures 76 x 40mm (3" x 1.55"). The board has provision for parallel capacitors and series resistors to ensure that you can get close to the calculated values without difficulty.

A quick word is warranted here, to allow you to determine if the speaker you have will actually work in a small sealed enclosure. The Linkwitz transform circuit (or EAS principle) will allow any driver to extend to 20 Hz or even lower. A good quick test is to stick the speaker in a box, and drive it to 50 or 100W or so at 20 Hz - you should see a lot of cone movement, a few things (hopefully externally) will rattle, but you shouldn't hear a tone. A 'bad' speaker will generate either 40Hz (second harmonic) and/ or 60 Hz (third harmonic) - if you don't hear anything, the speaker will probably work in an equalised sub.

If a tone is audible, or the speaker shows any signs of distress (such as the cone breaking up with inappropriate and unrelated awful noises), then the driver cannot be used in this manner. Either find a different driver, or use a vented enclosure. This is covered in a bit more detail below.

The schematic for a complete equaliser is shown in Figure 1, and considering the flexibility of the circuit, it is not at all complicated. The complex part would normally be determining the component values based on the speaker driver's response in a given enclosure. This is simplified by the spreadsheet, which requires only a small amount of input from you to be able to calculate the box response, and the equalisation needed to achieve the desired response.

Figure 1 - Complete Linkwitz Transform Circuit

In some cases a simple mixer circuit may be needed to combine the two channels. If so, use a pair of 10k resistors from each channel and use the centre tap as the input. This mixer is simply be added to the front end of the circuit in Figure 1. The mixer stage does not completely isolate each channel from the other, since the summing point is not a 'virtual earth'. The first opamp (U1A) is used only as a buffer/ inverter, so the polarity of the signal may be switched to find the optimum setting. When the switch is in the 'Norm' (normal), the phase setting of the equaliser is non-inverting (both the input and Linkwitz transformer are inverting). Setting the switch to 'Inv' (inverting) reverses the phase. You may need to experiment a little with the value of C1. The final value depends on the output capacitance of the preamp (the values of R5, R9 and R10 have been reduced from the original value shown, which was 100k).

Figure 2 shows the circuit of the Linkwitz 'transformer' with explanatory notes. The values of the unmarked components are determined using the Linkwitz Transform calculator spreadsheet (see below for more information). This circuit must be driven from a low impedance, such as the output from an opamp (as shown in Figure 1). The output capacitor as shown is a bipolar electrolytic, but a conventional polarised electro can be used if you prefer. The polarity will be different with different opamps, so measure the DC output voltage (it will only be a few millivolts) to determine the correct polarity.

As noted, to create a mono signal from a stereo source, a simple resistive mixer may be used. A resistive mixer requires that the source impedance from each preamp output is quite low to prevent crosstalk. If you are using a typical valve preamp, I suggest the use of buffer amplifiers prior to mixing, as the output impedance of most valve preamps is too high to allow resistive mixing without introducing crosstalk. This is not a problem if the summing inputs are used. In any case, the Linkwitz transform circuit will need to be driven from an opamp to ensure low source impedance.

Figure 2 - Linkwitz 'Transformer'

When designing the circuit from the spreadsheet, the dire warnings about DC gains above 20dB may be ignored, as the circuit shown has zero gain at DC. The input circuit has been designed to roll off (i.e. is 3dB down) at 7Hz, with a 6dB/Octave slope. The spreadsheet does not show this, but it must be considered regardless. Make sure that you read the section on 'Loudspeaker Driver Selection', as there are some important factors you need to consider.

I will issue my own dire warnings about excessive (greater than 20dB) gain at any frequency. Not allowing for the reduced radiating efficiency of any driver at very low frequencies, this is a simple case of determining the power requirements to obtain a flat response down to (say) 20Hz.

Let's assume that the power needed at 100Hz is 25W to keep up with the main system. If a given design shows that there is a 3dB gain at 50Hz, this means that 50W is needed for this frequency. As frequency reduces, the gain increases, and each 3dB of additional gain demands double the power. A mere 6dB of gain requires 100W, 9dB means 200W, and 12dB of gain means that 400W will be needed. For a gain of 15dB, we are now into serious power requirements, with a system power of 800W.

If you make the box as large as practicable, the amount of boost is reduced considerably - as always, there is a tradeoff between the allowable size of the enclosure, and how much power you are willing (or can afford) to use. The power limits of the driver itself must also be considered, and although most loudspeakers can tolerate transient signals higher than their rated power, they will have excessive distortion and may be damaged if excursion limits are exceeded.

Fortunately and perhaps surprisingly, the very low bass signals typically recorded for music are not that loud, so you will rarely need the full amount determined from the estimations above. One thing that is essential is to use a speaker with high efficiency - the higher the better. However, be warned that the LFE (low frequency effects) channel from movies on DVD or Blu-Ray can be very demanding indeed, and can require some extreme power levels to avoid clipping. On the positive side, they are just effects, so if the amp does clip, you may not even notice. Naturally, it's far better to avoid clipping if at all possible.

Selecting a high efficiency driver with a low free air resonance and a relatively small equivalent volume (Vas) means that the minimum amount of equalisation can be used. Again, each 3dB increase in efficiency means half the power is needed for the same SPL, so a speaker with 92dB/W/m is preferred over one with 89dB/W/m (all other things being equal), as only half the power is needed for any given SPL with the more efficient driver. There are physical constraints that make high efficiency at very low frequencies difficult to achieve.

Note: Always be aware of 'Hoffman's Iron Law'. 1 - Bass Extension. 2 - Efficiency. 3 - Small Enclosure. Pick any two. Having all three goes against the laws of physics and isn't possible, no matter how much you'd like it to be otherwise.

I will not suggest drivers, and it is entirely up to you to find suitable components based on manufacturer's details. I suggest that you look at loudspeakers intended for car sound systems, as these usually have a reasonable efficiency and low Vas. The range is enormous, and there are many excellent drivers that will not cost the earth. There are also many other excellent drivers that will cost the earth - your choice.

Apart from efficiency, Vas, resonance (etc), also consider the excursion limits of the driver. A speaker that has Xmax of 20mm will perform much better (and with a lot less distortion) than another similar driver with an Xmax of 10mm. In much the same way, a 380mm (15") speaker will produce more SPL with less excursion than a 300mm (12") speaker can. Also consider using multiple smaller drivers - two 300mm drivers have more cone area than a single 380mm speaker, and can therefore move more air.

A simple test for drivers is to apply a signal at 20Hz from a clean audio oscillator and power amplifier. Using an amp of about 100W or so, and with the driver mounted in an enclosure of no less than about 28 litres (1 cubic foot), increase the level until the amp starts to clip - this will be immediately audible! Just below the clipping level, listen carefully for any audible frequency that is not 20Hz (which itself is virtually inaudible). In particular, if you hear 40Hz or (more likely) 60Hz, the speaker is distorting, and generating harmonics. With a good driver, you should be able to see the cone moving back and forth, but should only feel the air movement - no audible harmonics should be heard.

| Please Note: There are some drivers that look like they cannot be used with the Linkwitz transform circuit, due to the combination of driver parameters. On the spreadsheet, there is a value 'k' that must be positive, but with a driver having a particularly low Q, the value for 'k' may consistently show a negative number, regardless of box size or anything else you can change. If you have such a driver, it may appear that it can't be used, but this can be corrected by a couple of different techniques. If this applies to your driver, please read on ... |

The 'Linkwitz Transform Calculator' tab in the spreadsheet has provision to select the desired minimum frequency and total system Q, and the 'k' value shown must always be positive. As noted above, with some drivers 'k' will be negative given the speaker parameters you add in the 'Box' tab. The most common reason for a negative 'k' value is a speaker with an unusually low Qts (total driver Q). The easiest way to get a result is to cheat - simply increase the driver's Qts figure in small increments until 'k' becomes positive.

Doing this will affect the accuracy of the final result, but the error introduced will generally be small compared to the errors created by the room acoustics. If you want to get an accurate final circuit, you will have to increase the Qts of the driver. You may think that's not possible, but it's actually quite easy. The simplest way is to use a resistor in series with the driver - it usually doesn't need to be more than perhaps a couple of ohms. This will (of course) get hot, as it may dissipate significant power, and overall efficiency is reduced. You also need to be careful - in some cases the spreadsheet will suggest impossibly large capacitor values if the Qts entered is too low, so you may have to experiment until you get something that can actually be built.

The alternative to using a series resistor is to modify the power amplifier so it has a higher than normal output impedance. The way this is normally done is to include a low value resistor in series with the speaker, and use the voltage dropped across the resistor to provide feedback that's related to the current drawn by the loudspeaker. See Impedance - Damping Factor for a brief introduction to this technique, and Effects Of Source Impedance on Loudspeakers for some measured results. Project 56 describes the method used to modify the output impedance of an amplifier.

Making these changes can be trivial with some amplifiers, but can be close to impossible with others. Several ESP designs have provision for current feedback for just this reason, and it's a technique that I've used for over 40 years for one reason or another.

Let's look at a hypothetical driver with the following characteristics (these are inserted in the 'Box' page) ...

Measurement Symbol Value Free air resonance fo 24 Hz Total Q Qts 0.38 Equivalent volume Vas 134 litres Box volume Vb 28 litres

We would like to get to 20Hz (-3dB), so insert these values into the spreadsheet. For Q(p) (total Q of 'transformed' system) of 0.8, we get a very small rise before the rolloff starts, which extends bass response marginally.

Now, select a value for C2 - this will determine the values for the remaining components, and is a compromise. As its value is increased, the resistances needed are reduced (this is good), but the value of C1 increases (sometimes to rather large values - this is bad).

I have been asked for definitions of 'good' and 'bad' in this context, so here they are ... 'good' is resistance in the range of about 2.2k up to around 220k or so. Lower resistance loads the opamp, and higher resistance may increase noise levels. 'Bad' capacitance values are those that are big and expensive, and if possible, I suggest that you keep the maximum capacitance below 2.2µF or so. Higher values will not hurt anything, but are bulky and expensive, or (in the case of non-polarised electros) may be small and cheap, but have a wide tolerance so accuracy will be compromised.

In the end, you will have to settle on values that are probably outside these goals, and noise is not really a big problem at low frequencies - especially with relatively inefficient drivers. The primary aim is to get values that are available - designing the perfect circuit is pointless if you can't get the parts to build it.

With the selected value of 56nF for C2, the following values are calculated for the remaining components ...

| Component | Calculated Value | Use ... | Actual Value | Error |

| R1 | 8.44 k | 8k2 + 220R | 8.42 k | 0.24% |

| R2 | 36.98 k | 33k + 3k9 | 36.9 k | 0.22% |

| R3 | 70.32 k | 68k + 2k2 | 70.2 k | 0.17% |

| C1 | 1.905µF | 1µF + 1µF | 2 µF | 5.0% |

| C2 | 56 nF | 56 nF | 0% | |

| C3 | 228 nF | 220 nF | 3.5% | |

| Maximum gain | 18.41 dB |

It will be necessary to use resistors / capacitors in series (or parallel) to obtain the required values - this can often be quite irksome, but only needs to be done once. A final error of up to 5% is almost certainly going to be OK, as the speaker characteristics will usually vary much more than this, and our hearing is incapable of resolving such small errors - especially when the room acoustics interact with the total system!

Figure 3 - Response Curves

Note that the maximum gain is over 18dB - this is rather high, but the energy levels at such low frequencies are actually very low as well, so although it may seem that an enormous amount of power will be needed, this is probably not really true in reality. Note that this is the response of the transform circuit alone, and does not consider the input filter shown in Figure 1. This has a -3dB frequency of 8Hz with the 100k and 100nF values given.

To work out the theoretical power requirements, let's have a look at the speaker sensitivity. We will make an assumption that it remains constant although this is rarely true as the frequency falls, due to the radiating efficiency of the driver itself. The assumption will work out well enough in practice (he says from experience).

Assume a quoted efficiency of 90dB/W/m as a starting point. For 'normal' high level listening, an SPL in the listening room might be around 100dB, which represents a power of 10W. Remember, this is worst case, and assumes that the LF energy level is the same as at upper frequencies. For all practical purposes, the lowest frequency is about 25Hz - our ears respond very poorly to anything lower.

For what it's worth, a good source of a 25Hz signal is the heartbeat at the beginning of Pink Floyd's "Dark Side of the Moon". This should rattle windows, and be felt as much as heard.

So, 10W to get 100dB (which is pretty loud), and we have a 15dB boost at the 25Hz point. Since each 3dB increase involves doubling the power, we get the following ...

First, the power needed to get to 100dB ...

Power 1W 2W 4W 8W 10W SPL 90dB 93dB 96dB 99dB 100dB

Now, the power to maintain 100dB as the speaker rolls off and the equalisation compensates ...

Power 10W 20W 40W 80W 160W 320W 640W Boost 0dB 3dB 6dB 9dB 12dB 15dB 18dB

This is not entirely correct with music signals, because the above figures are for steady state signals, and music is transient in nature (well, most of it, anyway :-). Peak power levels may be much higher at some frequencies, typically around 70-80Hz where kick drums make most of their noise, but the amp has copious reserve power at these frequencies. The underground railway rumble in that otherwise wonderful orchestral recording will be at a very low level, and most music has very little below 30Hz. If you enjoy pipe organ music, I suggest two to four 380mm drivers in a reasonable sized box (around 50 litres per loudspeaker), and equalised as described here. To get realistic response to 16Hz will require about 300W per speaker, for a quoted sensitivity of 90dB (actual figures will vary depending on the drivers selected, of course). This will be truly awesome, and if your dwelling survives, you may be able to defray some of the system costs by acquiring adjoining properties at an advantageous price.

The biggest benefit of a subwoofer that goes to such depths is that you will find yourself listening at lower levels than before, since the 'feel' that used to require an SPL of perhaps 110dB or more, is now attainable at maybe 95dB SPL. There is no loss of realism - indeed it is enhanced - and your ears will love you for it, and for all the right reasons.

The PCB for this circuit is available, and the circuit is exactly the same as that shown above. Mixing can easily be done using a pair of (say) 10k resistors from each channel to the input, provided the impedance is low enough from the preamp to prevent crosstalk. All 'solid state' preamps should be fine in this respect, but valve preamps will usually have a higher output impedance than is desirable, so buffers may be needed.

If you don't want to use the phase switch, the Com and N/O (Common and Normally Open) pins can be linked on board to give a non-inverting configuration (note there are two inversions in the circuit). Link Com and N/C for inverting operation. Phase can be reversed by swapping the speaker leads.

Because of the DC gain in the circuit, I suggest that you would (ideally) use a non-polarised cap for C8. In reality, any standard polarised aluminium electrolytic cap will most likely be perfectly alright because the DC offset will never exceed a few hundred millivolts. Because of the different way opamp inputs are configured, the output may be positive or negative, and I cannot predict which way it will go since constructors will want to use different opamps. For example, the polarity that is correct for a TL072 will be reversed if a 4558 were to be used, since the latter has a bipolar input instead of FETs. The exact offset voltage is also difficult to predict, but using the TL072, it should be less than 50mV. Other opamps can be expected to be similar. Because the circuit may have significant DC gain, DC offset is higher than most opamp circuits.

A polarised electrolytic can normally be expected to last forever with reverse polarity, provided the voltage (AC and DC combined) remains less than 100mV at all times. It may be necessary to increase the cap value if any electro is used to minimise the voltage across it at very low frequencies, as this can create distortion. Any capacitor distortion will typically be at least an order of magnitude below that of the subwoofer driver though.

This circuit was devised to be as cheap as possible to build, which means avoiding close tolerance and/ or odd value components. The PCB provides for parallel connection of caps for C1 and C3, and series resistances for R1, R2 and R3, since these will usually be odd values (as shown above). This is more convenient than specifying E48 series resistors and trying to obtain often very odd capacitor values.

Figure 4 - Simulated (Green) and Measured (Red) Response

Figure 4 shows the difference between the simulated and measured response of the PCB version of the circuit. Capacitors and resistors were not selected, but were used based only on their marked value. The response shown is not intended to correct any particular speaker, but was done as a test while the newest board layout was being verified. The only significant deviation is below 20Hz, and this is because the input impedance of my Clio measurement system is low enough to cause additional rolloff via C8 (I used a 1µF output cap). This has caused about 1dB extra attenuation at 20Hz, but improves the rejection of infrasonic frequencies.

As is quite obvious, the differences are small, and in the greater scheme of things can be ignored. The room will cause far greater errors than the circuit.

Main Index

Main Index

Projects Index

Projects Index