|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 229 |

Most reverb systems use a mute at the output, which prevents reverb tank ¹ recovery amplifier noise along with the loud clanging you get if the cabinet is moved or bumped. Unfortunately, this also means that if you want to use the reverb 'tail' as part of your playing style, you're out of luck. It's certainly easy enough to mute the drive circuit so the 'tail' is retained, but all noises from the reverb tank will be present while you're playing 'dry' (no reverb).

This is unlikely to be seen as a problem by most players, but maintaining the reverb as it dies out can produce a very good effect. The answer is to use two separate muting systems, one for the drive circuit and another for the recovery amplifier. The idea is that the recovery amp's output signal will be allowed to continue for a preset amount of time, which depends on how hard the tank is driven and the decay properties of the tank itself. When the output is finally muted, it should be a 'soft' mute (not a switch) that fades out the reverb signal after the delay.

¹ A spring reverb unit is a metal chassis with input/ output transducers, and one or more springs which produce the reverberation effect. These are commonly known as 'tanks' or 'pans'.

For details of suitable reverb drive and recovery amplifiers, see Project 34 and/ or Project 203. For an in-depth article about reverb tanks in general, see Care and Feeding of Spring Reverb Tanks. These are ESP projects and articles.

There are many different ways to switch an audio signal, but for the minimum 'disturbance' during the switching operation, something a bit less brutal than a mechanical switch or relay is (perhaps) called for. If switching is performed with little or no signal, it doesn't matter, but that's a potentially heavy burden for a musician who may wish to engage/ disengage reverb at any time. We don't need to be too precious though, as 99% of all reverb switching operations are performed with a footswitch, which doesn't seem to cause anyone any grief.

For so-called 'soft' switching, there are two options - LED/ LDR optocouplers or JFETs. It's up to the constructor to decide if this is warranted, because it adds significant additional circuitry that many will find excessive. The range of available JFETs shrinks nearly every day (or so it seems), but there are a few JFETs designed for switching, but not necessarily for audio. JFETs also introduce significant distortion, and while this can be reduced to a degree, it's never entirely satisfactory unless the level is kept below 100mV, and preferably less.

The other option is a Vactrol™, either 'name-brand' or home-made. Details of how to build your own are shown in Project 200, and I've had very good results from those I've put together. These have the advantage of low to very low distortion, even at high signal levels (> 1V RMS). However, they can be a bit fiddly to get just right when used for muting. JFETs are no different in this respect.

A basic JFET muting circuit is shown in Fig. 1, and while distortion is high when the signal is attenuated by 6dB (which is worst-case), it's only present for a fairly brief period. A single JFET doesn't provide enough attenuation though (at least not if you use a J113). With the values shown, maximum attenuation for a single JFET is ~35dB, so it's better to use a pair, connected one after the other. Each needs its own separate gate network, which is used to apply 50% of the drain waveform to the gate. This minimises odd-order distortion, but it's pretty much inaudible when the transition is less than ~100ms. This is far from the best option, as there are too many dependencies - see the article Designing With JFETs for all the reasons to avoid JFETs if possible.

Also shown is an LED/LDR circuit, and although it's shown with a +12V 'operate' supply, you can also use a 15V supply by changing R2. The amount of muting depends on the LDR's 'off' resistance, and a single stage will usually be quite sufficient. Dark resistance of a VTL5C4 is up to 400MΩ, with the resistance at 10mA LED current being 125Ω. The circuit is wired with the LDR in series with the signal, as this allows a rapid 'un-mute' and a relatively gentle 'mute', due to the characteristics of LDRs. They reduce their resistance quickly, but return to high resistance slowly, so no additional circuitry is needed to provide a gentle muting action.

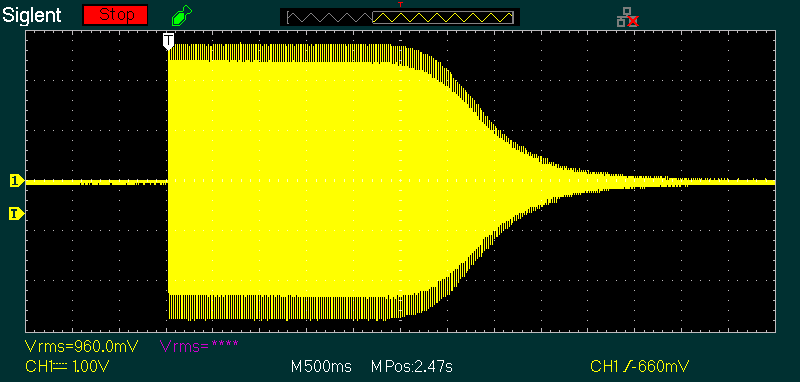

The control signal was turned on at the 3 second mark, and off at just before the exact centre of the screen, about 4.8 seconds after it was applied. The signal decays over a period of ~6 seconds, and after 10 seconds or so it's no longer (or barely) audible. Turn-on takes less than 2ms, so it's more than acceptable - the reverb signal won't have travelled the length of the springs in that time. In the final circuit, the time where the reverb return signal starts to be attenuated is adjustable, with a typical delay of between 5 and 10 seconds.

The JFET and LDR mute circuits have a relatively high overall impedance, so the output should be followed by a buffer or a gain stage. C2 is necessary with the JFET to remove any small DC offset introduced by C1, but isn't needed with the LDR or relay. The relay circuit's impedance is low enough that a buffer isn't necessary. With the LED/LDR version, you may need to separate the switching and analogue grounds to prevent a click if the control voltage is turned on quickly.

In contrast, a relay mute is much simpler, but is 'hard' - there's no transition, just a sudden application or removal of the signal. There's an almost imperceptible delay caused by the relay itself, but that's neither here nor there (it's well under 10ms if you use a miniature relay). All electronic versions have delays too, so that's not a reason to use one over the other. Overall, the idea of using a relay is far easier, and that's the method I ultimately decided on using for the input mute in this project. A more-or-less typical miniature relay has a coil resistance of about 1kΩ (12V types), so the coil current is only 12mA. The output mute uses the LED/LDR combination to get a smooth reduction of any residual reverb or recovery amp noise.

Because the contact resistance of a relay is so low, it's an easy matter to get the muted signal level well below 1mV (-60dB referred to 1V). This is possible with JFETs , but it's not easy to achieve. The relay circuit requires that the switching ground (SGND) and analogue/ signal ground (AGND) be separated. The current may be low, but it will contain 'hostile' artifacts that will be audible if the two are joined. Eventually they are connected together, but that should happen at the output of the power supply, not at some random location in the midst of the audio circuitry.

The general idea of a delayed mute is fairly simple. When you press the 'mute' foot-switch or whatever you use to turn the reverb on and off, the input is muted immediately. After a time that you can set with a pot, the output from the tank is muted. Input muting circuits uses a reed relay so you don't have any signal passing through a long cable to the foot-switch. The timer uses a common opamp rather than a 555 timer or similar, because it's easier to do. The 555 timer is very good, but the opamp circuit is actually a little simpler overall. The opamp is an LM358, used because they work perfectly with a single 12V supply, and can bring the output voltage close to zero. While other opamps can be used, they are much less convenient.

Output muting uses a Vactrol, wired as shown in Fig. 1, as this produces a natural decay rather than a sharp cut-off. The decay is still fairly fast as demonstrated by Fig. 2, but it's not instant, so you won't hear clicks as it operates. A Vactrol doesn't turn on instantly either, but the turn-on takes only a couple of milliseconds. Using the Vactrol this way means that no additional circuitry is needed to provide a 'fade-out' of the signal. The reverb output mute must be located after the reverb recovery amplifier or circuit noise may be a problem.

Q1 is any PNP transistor (e.g. BC556/7/8/9), and it's used so there's no high-current DC available at the switch or its socket. When the 'Ctrl' line is pulled low, RL1 turns on (allowing signal to the reverb drive amp), and C1 is charged via D2 and R5. This causes U1's output to go high, turning on the LED in the optocoupler and allowing the reverb output to be passed though to the reverb mixer stage. When 'Ctrl' is opened, Q1 turns off as does the relay, but the output of U1 remains high for the time set by VR1. When the timer expires, the output of U1 goes low, and the LDR changes to high resistance.

The delay is adjustable from 2.5s to 6.5s using VR1. During this time, the reverb output isn't attenuated, and the LDR is only turned off after the timer has expired. That prevents the reverb 'tail' from just being cut off suddenly. The input to the reverb tank driver is stopped instantly when the relay is de-energised. The delay circuit can also be adapted for use with tape or digital echo systems, with the output mute circuit being flexible enough to be adapted for longer (or shorter) times by adjusting the value of the timing capacitor.

The circuit is pretty much conventional in all respects, and there's nothing unusual about any part of it. The supply is shown as 12V, but it can be 15V if that's more convenient. The supply should be decoupled from the supply used for signal processing (within the reverb circuit) to prevent clicks when the relay is activated. This is accomplished by R10 and C2. Any low-current 'signal' relay can be used. These are often referred to as 'telecom' relays, and are usually DPDT so the NO and common contacts should be paralleled. They will draw about 12mA with a 12V supply.

I'd expect this circuit to be used with the Project 203 or Project 211 reverb system or similar. The P211 version is just the basics, and the P203 version uses almost identical circuitry, but includes an optional limiter. It also shows the output mute, which is replaced by the Vactrol if you add this muting circuit. The relay (input) mute would typically be connected to the wiper of the drive level control. If you make a direct connection, omit R3 (1k) in series with the relay contacts.

The traces show the drive signal (green) muted at the 2 second point, and the reverb output (red) mute is delayed for 4 seconds. The Mute is removed at the 8 second mark, and both signals (drive and reverb out) are restored immediately. The signal is just a simple sinewave with fixed amplitude, and that's to make it clear which signal is which. The waveforms were produced by the simulator, using the Fig. 3 circuit as simulated (as close as possible).

I expect that this project will probably have limited appeal, but it shows that you can retain the reverb fade-out (or 'tail') without compromising overall system noise. Most systems mute the reverb output, which doesn't sound natural. Skilled musicians should be able to have a lot of fun with the circuit, as you can selectively apply reverb during a passage, switching it in and out while retaining the normal decay of the reverb tank.

The 'soft' mute applied by the LDR means that the signal doesn't stop suddenly, but performs a fade (in film & TV parlance the is often called a 'fade-to-black'). Even if it's only residual noise that gets faded out, that sounds more natural than a sudden switch. When a signal fades it just goes away quietly, which is far less noticeable to the audience (although I sometimes wonder if most people would even notice).

There are no references, as the techniques described have all been used in other ESP articles and projects, and are generally well known. The way the muting circuits are used appears to be unique, and I've not found other examples on the Net.

Main Index Main Index

Projects Index Projects Index

|