|

| Elliott Sound Products | LED Lighting Comes of Age |

Main Index

Main Index

Lamps & Energy Index

Lamps & Energy Index

This article is now rather old (truly ancient in terms of LED lighting), and a follow-up will be coming in the near future. So much has happened, and the science gets better every year. LED lighting has come a long way in a relatively short time, and nearly 10 years (since this was written) is an eternity. There have been a few updates, but that doesn't do justice to the latest products. Luminous efficacy has improved dramatically, meaning that more of the energy put into modern LEDs is output as light and less as heat. This means heatsinks are smaller, and power supplies have also improved out-of-sight.

LED luminaires are now installed in their millions, and I'm pleased to say that my home is 100% LED - there are zero CFLs or incandescent lamps in use, with the sole exceptions of the oven, microwave and my now somewhat aged car. Ovens remain out-of-bounds due to heat and/ or moisture, and retro-fitting a car can easily violate Australian Design Rules that are applied to motor vehicles. Interior lights are LEDs of course.

It doesn't seem that long ago that we were quite happy with a LED luminaire that managed 50 lumens/W (lm/W), and that was equal to or better than most other light sources. Now, complete fittings are achieving better than 150lm/W, including the power supply itself - so the wattage is that drawn from the mains, and is not the output power of the supply.

Firstly, I have to say that I'm very excited. Spectrum Lighting (in Brookvale, NSW Australia) has been kind enough to donate and loan me a variety of LED lighting equipment, and I have no hesitation in saying that this really is the way forward for domestic, commercial and industrial lighting. I am more than happy to promote the company and its products - and not just because they gave me stuff. Readers of my site know full well that if I think something is good I'll say so, and if I think it's rubbish I'll say that too. If I promote anything on my site, it's because it deserves promotion and isn't simply because someone gave me things to play around with.

LED (light emitting diode) lighting products have really come into their own of late, and some of the offerings I've seen recently are really so amazingly good that it's hard to imagine they can be improved. Yet improve they will. We can expect to see higher efficiencies, better colour rendition, and luminaires that are designed around the LEDs. Replaceable globes will become a thing of the past when a light fitting can be expected to operate 24/7 for over 10 years. In normal use, these new fittings are perfectly capable of lasting well past the time when most people would want to renovate their home.

LEDs are perfectly dimmable, and are even better than incandescent lamps because the efficiency is not reduced when the LEDs are dimmed (note that this may not apply where a phase controlled dimmable power supply is used). With very high overall efficiency, mood lighting will be available to all who want it, without needing to feel that they are wasting power. There is no life reduction caused by on/off cycling as with fluorescent lamps (both traditional and compact), so LED lamps can be used for innovative lighting techniques that are simply impossible (or impractical) with any traditional technology.

When a power supply is introduced, the overall efficiency of a dimmed LED lamp depends on the power supply itself. A 150W AC-DC supply I tested draws 6W with no load, so if LEDs are dimmed to almost off (say 4W total from a 150W LED array), the efficiency will be very poor. However, when compared to an equivalent incandescent light source,the benefits are very evident. For a total power of around 4W for LEDs plus 6W power supply overhead, the total is around 10W. Any incandescent lamp dimmed to about the same brightness will draw a great deal more - somewhere around 20-25W is a reasonable estimate. The LED lighting system is still better by over 10W, and using a higher efficiency supply with lower overhead will improve this further.

Because there isn't a great deal of heat generated compared to incandescent or compact fluorescent lamps, lights can be placed in positions never possible before, and without regard to ease of replacement. Remember that LEDs are rated for a typical 50,000 to 100,000 hours operation, so even using the lower figure and assuming 6 hours a day for residential use, the LEDs will last for almost 23 years.

It's actually more likely that the power supply will fail before the LEDs, so we'll see a change from replaceable lamps to replaceable power supplies and/or controllers. As technology improves, the reliability of the power supplies will hopefully match the LEDs, but some of the necessary parts have lifespan limitations - especially electrolytic capacitors. These are responsible for many failures with existing CFL technology. This is largely due to heat stress, and is unavoidable in anything that gets as hot as a CFL. This doesn't apply to LEDs though - they have no filaments that must be heated, no fragile glass tubes, no mercury, zero ultraviolet output and relatively low heat output. However, for longest life the LEDs need to be kept as cool as possible. Heat remains the last obstacle for LEDs, because they need a heatsink to keep the light-emitting semiconductor junction cool. As luminous efficacy improves, we'll get more light with fewer Watts, but adequate heatsinking will still be a requirement for the foreseeable future.

Although most people would be unaware, the Times Square ball (used in New York to indicate the arrival of the New Year since 1907/8) was illuminated by over 9,500 Philips Luxeon LEDs for its 100th anniversary - the change from 2007 to 2008. Prior to that, the (now) 1.8 metre diameter ball was lit by incandescent lamps, and in December 1907 was undoubtedly a spectacle never seen before. It seems doubtful that the ball will ever see another incandescent lamp in the future, because the LED arrays are ideally suited to very sophisticated computer control allowing displays that were never possible before.

Quite obviously, there is no single lighting technology that is perfect in all respects. Sunlight is the standard against which all lighting must compete, and no artificial light source can equal the spectral distribution of good old sunlight. Some sources come very close, and the humble incandescent lamp (in one guise or another) will still be needed where an extremely high colour rendering index (CRI) is needed. Being almost perfect in this respect, incandescent lighting will probably never go away for some applications.

Fluorescent lights can also achieve a CRI of at least 80 (100 is ideal), but few of the presently available compact fluorescents can manage a CRI of better than about 70. Most LEDs intended for lighting are now very similar to traditional fluorescent lighting at present, and we know they will get better. So-called white LEDs from only a couple of years ago were anything but white, having a decidedly (and very obvious) blue hue. Most of the cheap white LEDs as used in torches (flashlights) are still the blue-white types because they combine low cost and high luminous efficacy (lumens per Watt, lm/W). White LEDs use blue emitting chemistry (typically Gallium-Nitride - GaN), with the addition of a 'colour shift' phosphor that absorbs much of the blue light and shifts the spectrum to approximate white. The combination of improved LED output and better colour shift phosphors has allowed some LEDs to reach (or exceed) 100 lm/W - this is very impressive.

As of 2013 LEDs are available with as much as 180lm/W, although 160lm/W is probably the upper range for normal commercial products.

Recently, LEDs intended for lighting have improved quite dramatically, with colour temperatures ranging from 3,500K to 6,500K. Compare this to a quartz halogen photoflood lamp with a typical colour temperature of 3,200K and a perfect CRI (100, the maximum possible). Colours observed under a photoflood lamp appear exactly the same as they do in sunlight - a lamp that caused the colours to change in a photograph would be useless. Think in terms of the green tinge that one sees in photos taken under fluorescent light (or from a LED streetlight - see below).

Some LED lighting is unsuitable where a very high CRI is needed, and are not really suitable for photography. While many mobile phones use a LED as a flash, the results are usually satisfactory. Many portable floodlights for home (and professional) video cameras now use LEDs. Xenon flash tubes still reign supreme for high quality photographic work, and this is unlikely to change in the near future. High quality photography is not a major user of electricity though, and for the majority of general lighting applications a high CRI is nice to have, but not essential.

There is no doubt that the relatively poor CRI of some LED lighting will influence their usage in some applications, but there are so many other benefits that it's probably safe to say that the CFL is a dead product before it has even gained significant traction in the marketplace. While (stupid) government intervention plans to ban incandescent lighting in many countries, the ban will probably fail in the form(s) presently proposed. The CFL simply has far too many problems to appease the people who will be forced to use them, and they pose significant issues for disposal and reclamation of the mercury.

So, some LEDs have a relatively poor CRI, but there are so many advantages that nothing will stop them from becoming mainstream, and LEDs are rapidly becoming the lighting method of choice. With zero mercury, disposal (after 10-20 years!) isn't a problem, and there are no other toxic materials that are likely to leach out in landfill. With the luminous efficacy now as high as any other light source (at least in prototype stage), they routinely reach around 90 lumens/Watt. This is higher than most tubular fluorescent lamps, and far better than any compact fluoro developed so far.

In addition, LEDs have an infinite dimming range. Light output is controlled by varying the average current through the LED (using pulse-width-modulation techniques), and it can be set anywhere between zero and the maximum permitted current for the particular device. Use of switchmode dimming systems lets us vary the current with almost no losses, so the overall efficiency remains high. Incandescent lamps are also very easily dimmed, but traditional dimmers present a very unfriendly current waveform back into the electricity grid and lamp efficiency falls dramatically. Far better dimmers can be made, but there is little incentive because of greatly increased cost and very little demand.

While fluorescent lamps can be dimmed, this requires special wiring and purpose designed dimmers. The results are often less useful than expected, and the vast majority of fluorescent lamps are run at full power whenever they are switched on.

| Lamp Type | Lumens/Watt | Temperature | CRI | Colour Temp | Life (Hrs, Typ.) |

| Incandescent | 12 - 35 | High (>150°C) | 100 | 3,200 K | 500 - 2,000 |

| Fluorescent | 45 - 100 | Med (~60-80°C) | 60-80 | 2,900-6400 K | 8,000-16,000 |

| Mercury Vapour | 5 - 55 | Med (>80°C) | 50-70 | 3,200-10,000 K | up to 20,000 |

| Metal Halide | 65 - 115 | High (>150°C) | 80-90 | 3,000-20,000 K | up to 20,000 |

| High Pressure Sodium | 150 | High (>150°C) | 20-30 | ~1,900 K | up to 20,000 |

| LED | 50 - 100 | Low (<60°C) | 50 - 80 | 3,200 - 10,000 K | 20,000-100,000 |

The above is by no means complete, but does give an overview of the commonly accepted values. The above data are from Wikipedia, various websites (especially for HPS and MH lamps) and LED data sheets as indicated in the references section. There are additional lamp types not covered, such as xenon arc, low pressure sodium (LPS), sulphur and a few others. There is a vast amount of further information available, but it can be a daunting task to correlate everything. Doing so isn't necessary, because the above covers the majority of lighting used in commercial and residential applications. This information is intended as a guide only - it should not be used to make any selection of suitable lamp types for your application. The temperature column shows the typical temperature of the outer envelope - not the operating temperature of the filament, arc or semiconductor junction.

Some of the specialised lamps such as the xenon arc and metal halide have little fear of being replaced in the near future. While their ultimate efficiency may be lacking by comparison, they are used for specialised applications and can produce astonishingly large amounts of light for projectors, major sporting events and the like. Low pressure sodium (not listed) is still a clear winner for luminous efficacy, but use has declined dramatically in recent years because of extremely poor colour rendering.

Of all the advantages of LEDs, one of the most useful for many people is the complete absence of ultraviolet light. There are several medical conditions that make sufferers highly intolerant of UV light, and due to the proliferation of fluorescent lighting (including CFLs) this can make their life a misery. LED lighting will be a very welcome addition for those affected.

With no UV light, LED lighting will also be useful for illuminating artwork that would fade and/or disintegrate if subjected to ultraviolet for a prolonged period. However, the CRI needs to be improved before LEDs gain wide acceptance in this application. LEDs do need to be kept as cool as possible. Heat accelerates the ageing of the device, reducing its life. Most LED data sheets show that the light output at rated life is around 70% of that when new, where fluorescent lights (especially CFLs) are rated for 50% of light output ... provided the electronics survive for the rated life which experience shows is not as common as one might hope.

The single most important limitation of LEDs is their operating temperature. The light emitting junction should remain below 85°C, although Cree claim that full power can be applied at up to 100°C ambient temperature for some of their products. However, regardless of claims, the lower the temperature the better. Light output falls with increasing temperature, and most of the quoted figures are for a junction temperature of 25°C. Output can be expected to be around 90% of that claimed if the junction temperature is at about 60°C, falling further as temperature increases.

Maintaining the lowest possible junction temperature not only maximises light output, but also the expected life. With most electronic components (LEDs included) the rule of thumb is that life is doubled for every 10°C temperature reduction. The converse is also true, so if the temperature goes up by 10°C, life is halved. Operation at very low temperatures is not a problem for LEDs, so they are ideal for use in refrigerators, freezers, coolrooms and the like (large and small). Unlike fluorescent lamps (compact or tube), light output will be high immediately after switch-on. The low ambient temperature will actually increase the light output slightly and prolong the life of the LEDs.

All we need to do now is reduce the cost to a level that the average purchaser will consider acceptable.

I do not propose to discuss the manufacturing processes for LEDs. For those who are interested, there's a vast amount of info on the Net that describes the processes, and to try to repeat it here would be silly. The specific processes also change as new techniques are discovered, and many of the finer points will be carefully guarded secrets from various manufacturers.

As noted above, LEDs are light emitting diodes. Unlike incandescent lamps, the applied voltage must be current limited, and of the correct polarity DC. Individual LEDs cannot be operated from AC, although they can be used multiples of two in reverse parallel if AC operation is essential for some reason. This is fairly uncommon, and it's usually far easier to use DC.

For marine applications, AC is a better choice to minimise electrolytic corrosion, but this is easily accommodated as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Wiring LEDs For DC and AC

When LEDs are operated from a voltage source (battery, most typical power supplies, etc.), the voltage cannot be made to match the forward voltage of the LED diodes because it varies from one sample to the next, and falls with increasing temperature. Even a very small voltage change can result in an extremely large change in current. If the maximum rated forward current through the LED is exceeded, at the very least its life will be reduced, and at worst it will die almost immediately. Life is inversely proportional to the percentage over-current, and failure is almost certainly due to excessive localised temperature.

In Figure 1, R1 is included in each circuit to limit the current to a safe value. It is always preferable to ensure that the series resistance is kept as small as possible, because it represents a waste of power. Taking the DC version as an example, a quick calculation is in order so the problem is understood.

Vsupply = 9 Volts

Vled = 3.2 V (fairly typical of white LEDs)

VR1 = 2.6 V

Desired LED current is 300mA, assuming 1W LEDs, although many manufacturers allow up to 350mA continuous.

R1 = V / I = 2.6 / 0.3 = 8.67 Ohms

Power = I² x R = 0.3² x 8.67 = 0.78 Watt

The overall circuit efficiency is reduced because of the series resistance. If the voltage available were 12V, the resistor would need to be 18.76 Ohms, and it would dissipate 1.68 Watts - more than each of the LEDs. For a 12V supply, it would be far more sensible to use 3 LEDs in series. This would then need an 8 Ohm resistor, dissipating 0.72W.

The configuration used should be optimised for the available voltage if maximum overall efficiency is to be achieved. The ideal method is not to use a resistor at all, but use a switchmode power supply configured for a constant current output, rather than the more common constant voltage. These power supplies are becoming common - only a few years ago they were virtually unobtainable. In many cases they are included within the circuitry of the lamp, but are now also common as stand-alone supplies.

Figure 2 - Blue/White LED Forward Voltage vs Current

From the above, you can see that a small voltage change causes a large current change. This diagram is based on the graph shown for the Cree XLamp XR-E LED data sheet, but is typical of most LEDs of similar power. The forward resistance of this LED is approximately 1 ohm, and unless a current regulated supply is used the voltage and series resistance must be accurately determined (and stable) to ensure that the maximum recommended current is not exceeded.

When only AC is available, either of the two methods shown will work, but the version using a bridge rectifier is more convenient overall. Three LEDs can still be used in series for a 12V supply, and the resistor value will be reduced slightly because each diode will 'lose' 0.7V or so when conducting. This is also a power loss, and needs to be factored into the overall efficiency calculations. For direct AC applications, the overall efficiency will normally be lower than if a switching power supply is used. AC derived from the mains either directly or via a transformer is subject to fluctuations, and the series resistance used must be sufficient to ensure that the average current remains within specifications. Using a SMPS between the diode bridge and the LED(s) allows voltage and/or current to be held within tight limits as long as the voltage is greater than a minimum determined by the circuitry used.

Every Watt that is dissipated in resistors, diodes or other components is a Watt that doesn't get to the light generating junctions in the LEDs, and is lost as heat. To maximise efficiency, all circuitry needs to be carefully engineered to obtain the lowest possible losses. While electricity was cheap and plentiful, the odd Watt here or there didn't make much difference overall, but this is changing rapidly as 'cheap' and 'plentiful' fade from common usage in discussions that involve any form of energy.

The 'wasted heat' argument that has been raised many times in the CFL vs incandescent lamp debate still holds. In many countries and for much of the year, there is no such thing as wasted heat. However, the cost of obtaining the much needed heat by electrical means will become too high as prices inevitably increase. I don't know what the alternative may be in countries that don't have access to natural gas (for example), but this (like oil) is a non-renewable resource. Unfortunately, solar heating works best in areas that don't need heating - an unfortunate twist in a world that often doesn't make much sense.

Geo-thermal heating (as well as power generation) is not available everywhere. In many cases, while it may be an option (as is the case in parts of Australia), the heat sources are a very long way from those who need the power. Long distance power transmission is not only expensive, but also wastes a significant amount of power due to resistance in the power lines. Iceland and New Zealand (for example) make the maximum possible use of geo-thermal energy, but not everyone is able to tap into this resource.

Some of the new LED lighting ideas are almost unbelievably good. One that I have already featured is the LED Tube Light™, details for which are in the article Traditional Fluorescent Tube Lamps & Their Alternatives. After looking at, dissecting and evaluating many products for the importer, I know that this is only one of many very exciting lighting products - all using LEDs. The latest LED tubes are a huge advance again - featuring power consumption of typically 18W to match a 36W T8 fluorescent tube and with a power factor of 0.95 being typical, these tubes blitz the other technologies.

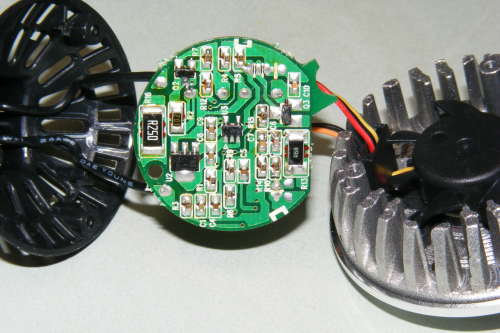

Some of the products include a bi-pin halogen downlight (MR16 compatible) replacement lamp. Just like any other downlight, it operates from 12V AC and works with iron-core and electronic transformers, and draws only a rated 8W. A visual comparison between a LED and halogen lamp reveals that the light output is a little lower (measured at 370 vs 530 lumens at 850mm from the lamp), but the power difference is huge. Note that the visual difference is not as great as may be implied by the measured difference. My halogen lamp (which is used under my workbench so I can find things I've dropped) draws 50W including the "electronic transformer" (a switchmode power supply), but the LED lamp draws only 6.48W, using either AC or DC. A photo of the insides of the LED version is shown below.

Figure 3 - LED Downlight - Internal View

Yes, that is a tiny fan you can see on the right. Because the lamp is so small, heatsinking the LEDs becomes an issue, so the fan was included to keep the temperature down. The fan is a 3-lead type, so the electronics knows if the fan stops and will flash the lamp as a warning. While standard halogen downlights have been responsible for a number of house fires* because they get so hot, this is a very unlikely scenario with the LED replacement. The ability to operate just fine with 12V DC is a benefit too, since it can be powered from a battery if desired. The electronics includes current limiting for the LEDs, so the light output does not vary as the voltage changes, until it drops below about 10V. Any DC voltage from 11V up to 15V only changes the current drawn - it falls as the voltage is increased, keeping the power usage about the same regardless of supply voltage.

With all electronics, maintaining the lowest possible operating temperature is important, and prolongs the life of the LEDs, ICs and other electronics. Fortunately, the latest LED lamps are getting much better at dissipating minimal power, and the amount of heat that needs removal is much lower than any other light source.

Many of the issues with current LED technology are directly related to the fact that all currently available luminaires are made so that the lamp can be changed. We are entering a new era, where the light source will last so long that it will probably never require replacement. This makes it much easier to design the fittings to maximise heat dissipation to keep the LEDs cool, and simple modules will replace the standard bulb-shaped lamp. Other than for replacement in existing fittings, the days of the bulb (or globe) as we currently know it are definitely numbered.

* Australia's Choice magazine has indicated that in Melbourne alone, 57 house fires were caused by halogen downlights in an 18 month period up to July 2007. This figure is unlikely to be different for more recent periods or other cities of similar size, but figures were not readily available. It is claimed elsewhere that halogen lamps can exceed 300°C when they are inadequately ventilated.

Without doubt, one of the most seriously impressive of the lighting I've ever seen is a 140W LED street lamp. This was loaned to me to run a few tests, and I have never seen so much light with so little heat. It lights up my (large) back yard so well that it's almost hard to believe. Two 150W quartz-halogen floodlamps I had installed outside are totally insignificant by comparison.

I ran some measurements, and it pulls 141.5W from the mains. With a measured power factor of 0.936 it is quite friendly to the supply companies. Although it's unlikely that I'll get the chance, it would be interesting to compare power factor and waveform distortion of the LED lamp with the more established types. The LED lamp easily outperforms most other lamps and should outlast all of them - including the few that have a higher luminous efficacy. Of these, high pressure sodium vapour is common and achieves around 150 lumens/Watt. Metal halide is still marginally better than LEDs, but I don't expect this situation to remain for long - at least for the power levels normally found in this application.

I have since had the opportunity to test and evaluate LED floodlights as well, with power ratings from 50W up to 300W. With an almost perfect power factor (0.97 or better is typical) and large heatsink area so the LEDs remain cool, these are state-of-the-art lighting fixtures, and are unmatched by any other technology. The latest streetlights use virtually identical power supplies.

Of the other technologies, few even come close. Low pressure sodium vapour lamps have the highest luminous efficacy of any known lamp type (around 180-190 lm/W), but are monochromatic, having only one dominant wavelength. They were very common for street lighting, but seem to have fallen from favour because they have a colour rendering index of almost zero - this makes identifying a vehicle by colour virtually impossible. The only other light that comes close is the high pressure sodium lamp (HPS) - around 150lm/W and 20,000 hours typical life, but maintenance costs and power factor also have to be considered. HPS lamps have a poor colour rendering index (around 22 is typical) - an important issue with street lighting because it is often necessary to report a vehicle's colour to police in case of an accident where the driver chooses to leave the scene. With a poor CRI, accurate determination of the real colour can be very difficult.

The LED lamp has a typical life of at least 50,000 hours, up to 100lm/W luminous efficacy and a good colour rendering index. Use of power supplies with active power factor correction is becoming standard (even for low power lamps). This means that the current waveform is almost sinusoidal - see Figure 4 for voltage and current waveforms. The streetlights and floodlights are both fully modular, so each LED panel and the power supply can all be easily removed and replaced individually if necessary.

Figure 4 - LED Streetlight - Current and Voltage Waveforms

The voltage and current waveforms shown above were taken using my PC oscilloscope. Ideally, the current waveform will be a perfect replica of the voltage waveform, but active power factor correction (PFC) hasn't come quite that far yet. The latest designs I've seen are far better than that shown though, with harmonic distortion of the current waveform well below 10% (this is far better than a traditional power-factor corrected fluorescent or other discharge lamp). The distortion of the voltage waveform is 4.5% with nothing connected, and doesn't change when the lamp is turned on. The current waveform distortion was measured at 10% and for mains this is a good result - believe it or not. At least some of the measured current waveform distortion is the result of the already distorted voltage waveform. Non-PFC switchmode supplies are being phased out for quality lighting products because they have far greater distortion, even at the same power rating.

Figure 5 - Photo of Back Yard Using LED Streetlight

The above photo is not retouched, other than being re-sized for the Net. The camera flash was turned off - not that it would have achieved anything useful at a distance of about 10 metres from camera to the tree. Just for a test, I turned on the two 150W floodlamps while the LED streetlight was on. The difference was barely noticeable, and no photo was taken since there was no point. For those who may be interested, the photo was taken with an aperture of F3.5, with a shutter speed of ¼ second. The photo doesn't do justice to the lamp or its illuminating power - visually, it is simply stunning, and the green tint is not seen.

The vast majority of residential street lighting will not need the power of this lamp. Spectrum Lighting also has a range of smaller units, and these would probably be more useful for general suburban roads. Since many of these (in Australia at least, but probably elsewhere) are either normal 36W fluorescent tubes, mercury vapour or high pressure sodium, a 30-60W LED lamp would make an ideal and less power hungry alternative.

It's definitely worth looking more closely at the lamp I have though, and some photos are shown below. Being modular, it's easy to look at the individual sections and I didn't even need to chop or pry my way in to see the guts.

Figure 6 - LED Streetlight Complete, Bottom & Top

Note that there's a plastic cover that was removed for access - the mounting bracket is normally covered. This is a fairly large unit, measuring 780mm long, 315mm wide, and 130mm high at the mounting end. The LED housing is only 80mm deep. It weighs just under 12kg, which is probably about average for a lamp of this size. This is the first streetlight I've had to play with, so direct comparisons are unavailable.

Figure 7 - LED Streetlight LED Module

The LED modules are each held in place by 4 metal thread screws, and the LEDs are under a moulded plastic cover that is well sealed against moisture ingress and insect invasion. Each module has 28 LEDs, which I expect are about 1.2 Watts each. All LEDs are mounted onto a substantial aluminium based circuit board, which is then attached to the heatsink visible on the back of the module. There will always be losses in the power supply, but will be fairly low - I'd be guessing, but around 7-10W would be typical for a supply having a typical efficiency of 93-95%. On that basis, each panel has around 30-33W of power to the LEDs.

While the heatsink might look like overkill, it isn't. After running for about 45 minutes, the heatsinks get quite warm to the touch. The LEDs themselves don't get noticeably hotter than the heatsink. I have no way of measuring the LED junction temperature, but monitoring the voltage across a panel shows that the voltage falls by 0.61 Volts (from 22.86V to 22.25V) - the LEDs in each panel are wired with 4 paralleled banks of 7 in series. The forward voltage of white LEDs falls by about 4mV/°C for each LED, so the junction temperature can be estimated at about 40°C (a rise of 22°C) after ~1 hour. The temperature coefficient may be anything between -3.6mV and -5.2mV/K for white LEDs, and as a result the temperature calculation can only ever be an estimate using this method (unless detailed data are available from the manufacturer). Measuring the heatsink temperature showed an almost identical temperature rise, so the calculation seems fairly close.

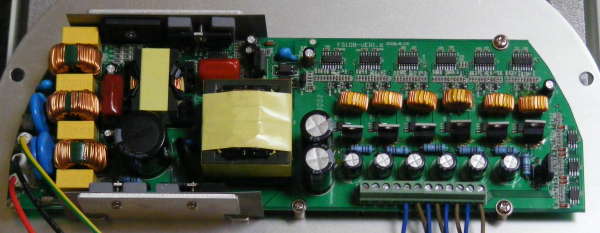

Figure 8 - LED Streetlight Power Supply

The power supply is in its own fully sealed enclosure, and features an active power factor corrected switchmode design. As you can see it is a substantial unit, and is obviously designed for long life. It uses generously sized transformers and inductors for minimum loss. Maximum output is probably around 200W. Overall, it certainly looks like it's designed to run for 20 years. Given that the output power is less than most computer supplies and the components are much larger, this indicates that losses should be very much lower. This also means less heat and longer life. All capacitors are rated for 105°C operation, and the power switching devices (which are heatsinked to the large finned panel) barely get warm.

The parts on the left side are the active PFC and main power supply switching converter, and on the right you can see six sets of identical parts. These are the individual LED panel current limit circuits, and the supply is obviously designed to handle up to 6 LED modules. On the extreme right is additional circuitry that appears to be for output monitoring and protection. The supply is definitely protected against short circuits - as I discovered when I accidentally shorted an output during testing.

These articles are a work in progress, as there are more LED ideas yet to be covered. Pages 2 and 3 cover some of the more recent developments, and further thoughts on the future of LEDs in lighting applications.

There are few references as such, because much of the data are derived from direct measurements taken in my workshop. Product photos are from lamps dismembered in my workshop I must thank Spectrum Lighting for the loan of the streetlight, and for a number of donated LED based lamps for me to pull to bits and play around with.

Some of the figures quoted for other lighting products (including LEDs) were obtained from Wikipedia and from several manufacturer data sheets including Cree and LumiLeds

Main Index

Main Index

Lamps & Energy Index

Lamps & Energy Index| Copyright Notice. This material, including but not limited to all text and diagrams, is the intellectual property of Rod Elliott, and is © 2008. Reproduction or re-publication by any means whatsoever, whether electronic, mechanical or electro-mechanical, is strictly prohibited under International Copyright laws. The author / editor (Rod Elliott) grants the reader the right to use this information for personal use only, and further allows that one (1) copy may be made for reference. Commercial use in whole or in part is prohibited without express written authorisation from Rod Elliott. |