|

| Elliott Sound Products | Electronic Transformers |

Main Index

Main Index

Lamps & Energy Index

Lamps & Energy Index

Many new installations using low voltage halogen lamps now utilise an electronic transformer. The traditional iron core transformer works well and will last forever, but they are relatively expensive. Some are also rather inefficient, wasting as much as 20% or more of the total applied power as heat. Electronic transformers are usually much smaller and lighter, so tend to lack the 'solid quality' feel, but most are either reasonably or very efficient, typically wasting less than 10% of the total power. Lower losses mean less heat and marginally lower power bills. Although the dissipation of each unit individually may seem reasonable, when thousands of them are running the extra loss becomes significant.

Below, I have provided details of one decidedly unsavoury electronic transformer. While its efficiency and power factor are as good as any, it is lacking in mandatory safety features and has no interference suppression components whatsoever. This is the ugly side of the lighting industry, because these products are available overseas for very low prices, but place the user/ homeowner at risk of electrocution or fire.

A conventional iron core transformer operates at the mains frequency (50 or 60Hz), and the core needs to be fairly large because of the low frequency. Core size is inversely proportional to frequency, so operating at high frequency means the transformer can be much smaller. The term 'electronic transformer' is really a misnomer - it is actually a switchmode power supply (SMPS). Electronic circuits are used to rectify the mains and convert the AC into pulsating DC. This pulsating DC is then fed to a high frequency switching circuit and a small transformer. Figure 1 shows a photo of a typical unit. This is not intended as an endorsement or criticism of the unit shown - it is simply an example (although there is nothing at all wrong with it).

Figure 1A - Electronic Transformer Internals

The mains terminals are on the right, and the 12V output terminals are on the left. There is an RF filter at the input, and two switching transistors that are not visible, but are TO-220 devices mounted on small aluminium heatsinks. The little green ring right in the middle of the photo is the transistor switching transformer (T1 in Figure 2), and the output transformer is the large black plastic object. This has a ferrite core with the primary windings on the inside of the plastic insulating housing, and the secondary (the 9 turn 12V output) is wound around the outside of the cover. The thermal fuse is just visible projecting from under the upper heatsink (it has long leads in translucent white plastic tubing). There are additional surface mount components on the underside of the PCB.

Note that R1 in the schematic may be a fusible resistor or a fuse. Either way, it is essential that it fails or blows cleanly with any fault current, without arcing, sparking, or shedding burning resistive material.

The output is not rectified - it is AC, but comes in bursts of high frequency signal (see Figure 3 for the output waveform).

Figure 1B - Electronic Transformer Internals

As a further example, Figure 1B shows another electronic transformer. The circuitry is almost identical, although it looks quite different. The small green transistor driver transformer is much more visible though. This unit does not have any surface mount parts under the board - everything is mounted on the top of the PCB. As you can probably guess, this unit is facing in the opposite direction (mains input at the left, low voltage output at the right).

Figure 2 - Electronic Transformer Circuit Diagram

T1 is the transistor switching transformer. It has three windings, the primary (T1A), and two secondaries (T1B & C). The primary is a single turn, and each transistor drive winding is 4 turns. T2 is the output transformer. DB1 is a DIAC (as used in most leading edge dimmers), and is used to start the circuit oscillating once the voltage exceeds about 30V. Once oscillation starts, it will continue until the voltage falls to near zero. Note that the basic output frequency is twice the mains frequency, so an electronic transformer used at 50Hz actually has a 100Hz output frequency signal, which is made up of many high frequency switching cycles. Although a 230V circuit is shown, those intended for 120V are virtually identical but use fewer primary turns. The circuit shown is representative - it is not intended to be a design for a working electronic transformer. It is included here so you can see the basic components and connections, and understand the principles of operation.

Most electronic transformers will not function with no (or light) loads. For example, a 60W unit will typically need a load that consumes at least 20W before it will function normally. With a very light load, there is insufficient current through the switching transformer's primary to sustain oscillation, so low power LED lamps typically cause the output to vary. This may cause visible flicker which can be very annoying. This happens because the current through the primary of T1 (T1A) is too low to sustain reliable oscillation.

Figure 3 - Output Waveform of Electronic Transformer

Although the waveform shown is exactly as captured by my PC based oscilloscope, the transitions that are clearly visible are an artifact of the digitisation process - the frequency is much higher than indicated. The RMS voltage of the waveform shown measured 12.36V, but it is a difficult waveform to measure accurately. I expect that the actual voltage was closer to around 10V as measured using an analogue meter (the nameplate rating is 11.5V but varies with mains voltage). Across a 2 ohm load (5A), output power was around 50W. The supply drew 231mA from the mains (52.2 VA). The measured input power was 52W, so power factor works out to be close enough to unity. Efficiency is almost 96% - a very respectable figure indeed.

Care must be exercised if using an electronic transformer with low voltage LED lamps or CFLs. Because these lamps have an internal rectifier, the diodes must be high speed types. Normal rectifier diodes will get extremely hot because the operating frequency is much higher than that for which ordinary diodes are designed. Although the waveform envelope is only 100Hz, the switching frequency is much higher - typically around 30-50kHz (frequency typically decreases with increasing load).

I must mention that the energy savings of electronic transformers may often be overstated. While conventional iron core transformers will last virtually forever, electronic transformers can fail at any time, and prove this by doing so. The high temperatures encountered in the roof-space of many houses stresses the semiconductor devices, and the widespread use of lead-free solder ensures that solder joint failures are not uncommon. I've seen several failed units, and while I may be able to fix some of these, 99% of householders will simply throw a failed unit away and install a new one. When manufacturing, shipping, driving to the shops to get a new unit or paying an electrician to replace a failed transformer are all considered, you may well have been better off to use an allegedly inefficient iron-core transformer instead. This may easily apply both from a purely financial perspective and overall greenhouse gas emissions created over the life of the product.

The vast majority of these transformers have been subjected to rigorous testing and certification. In Australia, they are classified as 'Declared Items' (formerly 'Prescribed Items'), which means that electrical safety tests are both mandatory and extremely thorough. To obtain CE certification, electrical safety tests are part of the process, and all CE marked products are tested for electromagnetic compliance (high frequency interference) and safety.

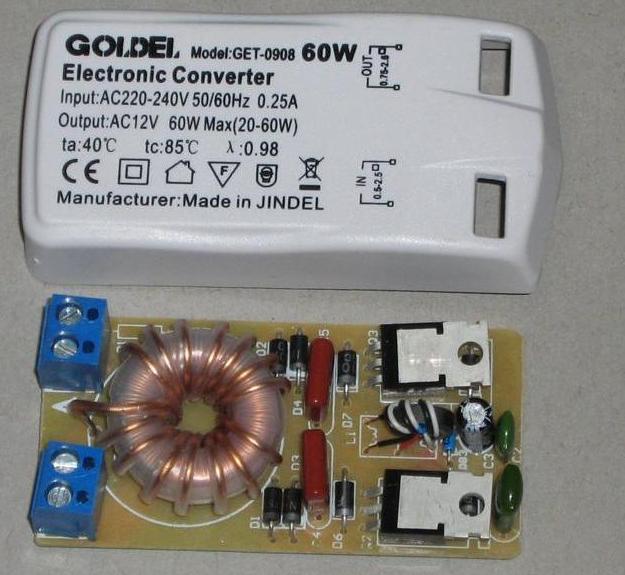

Normally, I do not show a specific (and named) product and point out the issues to readers, but this product is so dangerous that I had to show it so that it can be avoided. It is available direct from China, and because it appears to have CE approvals it might be thought to be alright to use. It isn't - it's potentially lethal, and may also cause unacceptable interference to radio or TV reception.

The transformer shown below displays a CE logo, but would not pass any basic safety test for a double insulated product in any country. The schematic shown above was simplified, and I omitted all protective and most interference suppression circuitry in the interests of simplicity. In the transformer shown below, they also omitted all protective and interference suppression circuitry ... in the actual product!

Figure 4 - Chinese Electronic Transformer With False Certifications

Essential safety items have simply been left off, so there is no mains cable clamping device or protective cover, there is no thermal fuse (normally fitted to all of these transformers), transformer insulation is low temperature and definitely not fail-safe, and there is not one single component to reduce RF interference in any way.

Figure 5 - Underside of Dodgy Electronic Transformer

Under the board, it is obvious that the necessary creepage and clearance distances have not been used. The minimum distance (highlighted with an arrow) is well under 4mm, while all properly made and certified units have a minimum distance of 7-8mm. The only concession to safety is resistor R1 (top right side of the picture) which will fail if the unit draws excessive current. Given the small distance between pads of surface mount resistors, it is likely that failure of R1 would simply allow power to cross the barrier via carbonised PCB resin and the remains of the resistor. As a 'safety' measure, it is woefully inadequate.

There is an alternative version of this transformer available too, but it has fixed (soldered in) input and output leads. Creepage and clearance distances are still well below the minimum required, and the circuitry is identical. Again, there is no protective thermal fuse and zero interference suppression.

I can only suggest that based on this, you remain vigilant. Do not purchase lighting (or other) transformers from overseas when you have to rely solely on the markings on the unit and have no way to verify that the product meets the regulations where you live. In Australia, it is illegal to sell any product on the prescribed articles list that does not have full safety approval. Much the same applies in Europe, and I doubt that anyone would be fooled by the CE logo for very long.

This is not the only product that completely fails to meet any mandatory electrical safety regulations - there are plenty of suppliers who are perfectly happy to create what amount to counterfeit parts. They will be cheaper than the competition because expensive safety tests aren't needed, and there are lots of components they don't need to install because no official test will ever be conducted.

The issue shown here is just the tip of the iceberg. A campaign was waged in the UK, with the slogan "Do not electrocute your customers with counterfeit electrical products", but based on a Web search it never gained much attention. However, it is simply impossible that these problems are limited to the UK and Australia - naturally they are worldwide, but like the counterfeit electronic component industry it tends not to be in the public eye.

When I launched my articles about fake parts there were only a very few other sites with any info at all on the subject. There are now hundreds of sites that point out the risks. Unfortunately, there is very little publicity given to fake electrical parts - the UK has had a big problem with fake (untested and unsafe) mains leads, and the same could happen anywhere.

Usually, if you buy a product from overseas, it will come with a mains lead. You might be 'lucky' and get one intended for your country, but is it approved? Has it undergone the usually mandatory testing to ensure that it complies with the local regulations? In most cases, the answer is "No" - it might fit the socket, but that doesn't mean that it is safe to use. You may well ask "What can go wrong with a mains lead?". As it transpires, quite a lot. Undersized conductors are common, to the extent that the cable overheats and may melt the insulation if used at its full claimed capacity. Poorly crimped or welded connections, the wrong grade of insulation, insufficient socket contact tension ... the list is endless. There is much more scope for failures in a complete electronic product of course.

Great vigilance is needed worldwide to ensure that only safe products that comply with local regulations are sold to the public. It's far too easy for an adventurous (or just unaware) small-time importer to assume that the markings displayed on a product are real and meaningful. Many will be unaware that many electrical products require mandatory testing - this varies widely from one country to the next, but the main standards are generally prominently displayed on legitimate products.

Be particularly wary of sellers on online auction sites - especially if they are based in China or Hong Kong. However, 'local' sellers can be just as bad, offering non-compliant products with no safety testing or approvals of any kind. I have seen electronic transformers and low voltage DC supplies for sale that certainly don't have Australian approvals, and other certifications (such as CE, IEC, etc.) are highly dubious at best and are probably fraudulent. Remember, this is not an Australian issue - houses can burn down and people can be electrocuted in any country, and most countries have rules, regulations and mandatory standards for low voltage power supplies. Some of the more common ones are ...

Never assume that a known brand must be alright - there is every likelihood that if it comes from China it's a fake. I found a seller offering 'Philips Electronic Transformer', but strangely, when I did a search the Philips website did not feature once - all references pointed to China. I then checked the Philips catalogue - the transformer I saw advertised doesn't exist according to Philips! It has to be suspected that a transformer from a Dutch manufacturer that has only Chinese writing on the box and the transformer itself is a wee bit suspicious.

For those who are in Australia but think I'm making mountains out of molehills, I suggest you read the ELECTRICITY SAFETY ACT 1971 - SECT 12. Although the link is to the ACT version, it applies Australia-wide. It is not only an offence to sell non-approved declared/ prescribed articles, but also to connect them to the electricity supply. Also, see Appendix E4 of the Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZS 4417.2:1996. (As with all standards documents worldwide you have to pay for access to the material, a serious case of poor judgement IMO. This is especially true where safety is involved!)

If you don't understand the requirements for your country, you may discover that you have unwittingly committed a serious offence and may be responsible for someone's death in the worst case. It is far better to pay a little more to a local reputable supplier to ensure that the product you purchase has been tested and is safe to use for the intended purpose. Avoid online auctions - there is little or no supervision, and trying to get them to act against unscrupulous sellers is slightly more painful than gnawing off your own elbow (and a lot less fun  ).

).

This is not a topic to be taken lightly. If you install a non-compliant product and your house burns down and/or your loved ones are killed or seriously injured, you are responsible. For the sake of a few quid, dollars, (etc.) it's simply not worth the risk. Safety standards exist for a reason, they are not there for someone's amusement or just to annoy you.

Main Index

Main Index

Lamps & Energy Index

Lamps & Energy Index