|

| Elliott Sound Products | Projects, DIY & Sustainability |

Main Index

Main Index Articles Index

Articles Index Most readers will be aware that I don't specify SMD (surface mount device) parts for any of the conventional projects, and all PCBs use through-hole parts exclusively. There is one project that (if/ when it gets a PCB) where there is no choice, as the IC is only available in SMD. All other parts would be through-hole, which will make almost no difference to the PCB size. This article explains why I steer clear of SMD unless there is no other choice, and also covers commercial products where there is no option for repair. There is no doubt that many of the latest parts are (only) available in SMD, but most are also available in standard through-hole format. If there is no alternative, then I will not shy away from an otherwise good idea just because the IC required is not available in a through-hole package.

I am a very strong believer in the 'Right to Repair' movement described below. Everyone has the right to fix anything they can, whether the manufacturer likes it or not. Some manufacturers go to extraordinary lengths to make it difficult or impossible to fix their products without highly specialised tools, and information that they refuse to make available to their customers. One company is a stand-out (and a repeat offender) in this area (you know who I mean  ). However, they are joined by countless others who make it just as difficult. This is quite unacceptable!

). However, they are joined by countless others who make it just as difficult. This is quite unacceptable!

The waste in our lives today would perplex our forefathers. In earlier times (when almost nothing was wasted), should a product become 'worn out', it was either repaired, or what was left was converted into a tool that could be used for something else. That's not to say that nothing was wasted of course, but what we see now has never happened before. If a washing machine finally gave up the ghost, there used to be every chance that the motor and some pulleys would be put to use to perhaps build a small concrete mixer or some other useful tool (a wood lathe for example). Now, you can expect machines only a few years old to be scrapped - hopefully recycled, but often not.

How many of today's cars will become classics, still functional after 50 or even 100 years? Countless TV programs show old cars being restored to their former glory, but few of the new vehicles built now will be around for much more than 10 years or so. There will be exceptions, but when a car maker designs a new model, it's not part of the process to design it so that it will last. The electronics will be particularly challenging - modern cars are overflowing with computerised functions, and these will be challenging to replicate because the information needed is not made available.

I have hand tools that are over 50 years old, and a few power tools that aren't that far behind. Likewise test equipment - several pieces of test gear are at least 40 years old, and are still in use. Part of the reason is that I can't afford the latest and greatest, but the gear I have wouldn't be scrapped even if I could afford to buy a nice new Audio Precision test set. They would either be sold to a collector, or given away to a good home. Some of the gear I have was obtained on that basis ('free to a good home'), and so it should be.

Once it was possible to find repair 'shops' for most appliances, but they are now few and far between. A big part of the problem is the lack of spare parts, especially controllers which almost all use a microcontroller or processor. These are proprietary, and usually impossible to service if the micro has failed. The program code won't be available from anywhere, so even if you can replace a faulty controller IC, without its program it's just a lump of silicon that will do nothing at all. Even the most mundane appliances now have some form of electronic control, and it's almost guaranteed that the electronics will fail well before the mechanical parts are worn out.

Washing machines can be an exception - the last one of mine that failed was a front-loading type, and the 'spider' (a cast aluminium frame that holds the bearings and supports the drum) fell to bits (literally!). Unfortunately, a replacement was going to cost almost as much as a new machine, and would take many hours work to install (I was able to find info on-line that showed what was necessary). It was deemed 'not worth repairing', as it would take several weeks to get the replacement part, and washing day can only be suspended for a short time before we'd run out of clothes. I did salvage as much as I could, but it wasn't a great deal  .

.

Fortunately, a council recycling day wasn't far off and the bulk of it didn't just go into landfill.

If you look trough the ESP project list, you'll see than some of the projects are 20 years old (at the time of writing this). Despite this, the projects are still just as relevant today as when first published. PCB layouts have been amended, and the boards sold today are of far better quality than the first ones offered. The components used are still nearly all readily available from most electronics parts suppliers, and only two projects are obsolete. There are others that indicate parts that are no longer made (JFETs for example), but most can be substituted for a different JFET with a few, usually minor, component changes. I usually avoid JFETs for this very reason - the range keeps shrinking, and no-one knows which will be the next to be declared obsolete.

The original version of the Project 26 digital delay used an IC that went out of production, and the Project 85 S/PDIF converter uses an IC that is no longer made. Every other project can be built today (almost) as easily as when it was designed. Of projects, analogue opamp ICs are easily upgraded to something the reader prefers, and everything else is done using standard parts that show no sign of disappearing. There are two primary reasons that most PCBs are single-sided, and use 'conventional' (through-hole) components. The first is ease of construction, and no-one will dispute that SMD parts are very small, and they can be difficult for most beginners as well as many experienced hobbyists. Because they are so tiny, it's incredibly easy for a part to simply 'disappear' - not literally of course, but they can fall to the floor and never be seen again. Even a slightly untidy workbench can be more than enough for a tiny part to hide under something else. In compliance with Murphy's Law, it will be found only after you don't need it any more.

An example where the only option is SMD is Project 198, which uses an IC that isn't available in any other format. Because of the very close pin spacing, many people find them difficult to solder onto a PCB. It requires either specialised equipment or a very steady hand and a fine soldering tip to be able to solder the part to the board without solder bridges, missed pins, or an IC that moves slightly and bridges tracks. Removal is irksome without the proper equipment, and the recommendation is that if an SMD part has been removed, it should be discarded. This is due to the enormous heat-stress placed on the part, both when soldered to the board, and again when it's removed.

Single-sided PCBs are easier to service than double-sided boards with plated-through holes. Ideally, you'll cut the component free first - especially ICs - as this ensures minimal PCB damage. You only need enough heat to melt the solder, and a simple plunger-style solder sucker will free the lead. The part's lead can then be pulled (or pushed) back through the board if it didn't get sucked out with the solder. If you do that with a double-sided board, it's likely that you'll also pull out the plated-through hole, which can make a complete PCB unusable. There are ways to fix a damaged plated-through hole, but the result is often untidy and may compromise reliability. Of course, some boards would be unreasonably large (or would require many links) if single-sided, so there are quite a few boards that are double-sided with plated-through holes. Projects have to be practical, and a large number of wire links doesn't fit that criterion.

With double-sided PCBs, unless you have a 'real' vacuum solder sucker, cutting off the component leads first is pretty much mandatory. Even with a vacuum desoldering tool, it's still the only way to be sure that the PCB isn't damaged. Multi-layer boards are even worse, but no ESP project uses them.

SMD is now so common that it deserves a section of its own. It must be understood that SMD is designed to make goods easier (and cheaper) to manufacture. With most, there is little or no consideration whatsoever given for repair, and the vast majority of SMD boards are expected to be replaced if (when) they fail. When you can no longer get a replacement board or module, the product is pretty much 'end-of-life'. It might be possible for a particularly stubborn service technician to find the fault and repair the board, this is usually limited to known failures, such as electrolytic capacitors.

In many cases, the parts have no printed values because the part is so tiny that there isn't room for any printing. Many SMD parts also have 'built-in' failure mechanisms, and although most do not fail, some do (as is to be expected). It's worthwhile to look at Resistor Failure Analysis, shown on the Gideon Labs website. Voltage and thermal stresses will cause any resistor to fail, but SMD types also have to withstand any flexing of the PCB material itself. Because they have no leads and are mounted directly to the copper tracks with solder, they cannot tolerate any flexing of the board. If the board does flex, failure is inevitable (and the failed part(s) can be almost impossible to locate)

It's also very common that products that once were expected to last for many years (professional audio gear used to be expected to last for 20 years or more) now do not. Because they use mainly SMD parts throughout, the equipment lasts only as long as the supply of replacement boards or modules. This will rarely be for more than five years, but 'low-cost' (or 'no-name') gear usually has no repair strategy at all. Once the warranty expires, the gear is often unserviceable. It might be possible to affect a repair if the failed component(s) can be identified and of a common type (e.g. electrolytic capacitors, MOSFETs or popular opamps), but failure of anything 'fancy' (SMPS or other specialised parts) usually means that the equipment cannot be repaired at all. This is depressingly prevalent.

Construction techniques that you see in much modern equipment make things even harder. It's not at all uncommon to see a folded chassis with the PCB at the bottom, and all of the high-power devices bolted to the chassis itself (with insulation in most cases). To get access to the underside of the PCB, you have to unbolt every device that's attached to the chassis before the PCB can be removed. Forget the idea of an 'inspection' plate or removable base - that rarely happens! Assuming that you can repair the board, to test it you must replace any silicone pads (they cannot be re-used), and bolt it back into the chassis. If the repair was not a success, then you repeat the whole process!

In the factory, they'd most likely use a test jig with clamps for the power devices and with separated heatsinks so tests can be run quickly without having to use silicone pads. The heatsinks have to be separated because most devices will not have any common connections to their mounting tabs. That this is impractical for a one-off repair is putting it mildly. These products are simply not designed to be repaired, they are designed to be replaced as a complete module! Unless you get very lucky indeed, the entire product is scrap once a single low-cost part fails and puts it out of action.

While the failure of a single part can render a product useless, in some cases there will be parts that can be re-used. Powered speaker boxes are an example, but it might be possible to replace the existing module with something that can be repaired later. An example of a project that can be used to resurrect a powered speaker is shown in Project 137, which was originally designed to replace Chinese modules that were a catastrophic failure in every significant respect. Many were built for a (commercial) customer, and have provided exemplary service for many years. More to the point, they can be fixed if one does fail!

The problems with SMD boards aren't going away, they are getting worse. Many through-hole components (some opamps for example) are no longer available in a through-hole package, and new parts are often available only in a surface-mount package. There is no doubt that electronics are cheaper now than ever before, but when that results is a shorter life and little or no chance of repair, the savings are often an illusion. For example, a $1,000 (at today's price) amplifier from (say) 1990 that's still operational after 30 years is a far better proposition than a new $600 amplifier that may last for 5 years or so before it can no longer be serviced. To get 30 years of life, you'll have to buy at least two, but perhaps five new amplifiers, with a cost of between $1,200 and $3,000. Not such a bargain after all, and to be a 'good citizen' you must consider the wasted materials as well.

The waste created by these new devices (not just amplifiers) is enormous. While the EU (European Union) has 'directives' that supposedly cover the recycling of waste electronic products, for most people it's an inconvenience, and it's not a requirement in most countries outside the EU anyway. For example, in Australia we are encouraged to recycle as much as we can, but there's still a great deal that goes into land-fill because it's easier to toss whatever doesn't work any more into the bin. Very few people will dismantle 'stuff' to see if there's anything potentially useful inside, because most people aren't technical, and would have no use for the bits they can rescue anyway.

Now that just about everything is SMD, these opportunities are disappearing very quickly. Very few SMD parts can be rescued, and the other parts are unlikely to be of very much use to anyone. A switchmode transformer is an example. It can (sometimes) be 'rescued', but unless you can duplicate the original circuit and it does something that you need, there's no point. Most are vacuum impregnated, and can't be dismantled (I know this because I've tried, and even using hostile chemicals it's still futile).

The component density of most SMD boards is very high. This means the PCB traces have to be much thinner than they'd be for a through-hole component. The high density also means that there is often more heat per unit area than is typical for through-hole boards. When combined with the idea that no-one expects the PCB to be repaired, this often leaves you with a board that can't be repaired.

High parts density also means that components that don't like heat (such as electrolytic capacitors) often run far hotter than is desirable, shortening their life. This can be particularly critical in SMPS designs, where even a modest increase in capacitor ESR (equivalent series resistance) can cause a switchmode supply to fail. Normally, ESR can be tested with the capacitor in-circuit, but only if you can get to its leads. Where the entire module has to be dismantled to gain access, it's likely that the service tech will simply say that it can't be repaired.

When you consider the purchase price of some of the gear around (often ridiculously cheap, even if paying retail) and the cost of a couple of hours of labour, buying a new one is often the most sensible option. You get a brand-new item for little more than it would cost to fix the old one, and it comes with a warranty. But, what happens to all the goodies inside the old one? If it's (say) a powered speaker, the loudspeaker and horn compression driver are probably fine, the box is still serviceable, and there are probably other electronics that are still ok too. Mostly, all of this will end up in landfill (or possibly, hopefully recycled). I case you were wondering, these last two paragraphs are based on a real scenario, with details provided to me by a friend who worked on a powered speaker. He discovered high ESR capacitors in the switching power supply that were replaced (albeit found and fixed 'unconventionally'). And no, a replacement module was not available.

All of the ESP project PCBs can be repaired easily. While some do use double-sided boards, if the recommendations are followed, they can be fixed as easily as any other project. Using double-sided boards is not something I take lightly, and if it can be done, the PCB will usually be single-sided because I know that people will have fewer problems.

I've always been a very strong believer in repair when possible. The idea of tossing away otherwise perfectly good electronics just because a $1.00 (or 10 cent) part has failed doesn't sit well with me at all, and many others feel the same. As discussed above, a PCB covered in SMD parts is virtually un-repairable for most people, and doubly so if no schematic is available from anywhere. This is becoming depressingly widespread, with many of the 'Far Eastern' countries pushing out thousands of cheap boards that can't be modified, and if (when) they fail, can't be fixed. Many manufacturers obfuscate or erase IC part numbers, thus ensuring that repair is unlikely or impossible  .

.

The waste of resources from this is astonishing. You only need to look along your street when there's a council clean-up day approaching to see what people are throwing away. Many of these items will still be working, but have fallen from 'fashion' (whatever that is) or the householder has been convinced to buy the latest model because ... it's the latest model. It may not do anything new that the consumer will use, but for some reason, they've fallen for the 'marketing speak' from the manufacturer and upgraded. In other cases, something has failed, and a replacement PCB is no longer available. (Most smaller items will likely just be tossed in the bin).

Note that it's a replacement PCB - not an individual part. In some cases, there is only one PCB, and it has everything on it. Once that board no longer works, the only option is replacement. As an example, about a year ago (at the time of writing) my TV gave up the ghost. It's not a cheap "I've never heard of them" model, but a 'name' brand with a fairly good reputation overall, and it wasn't inexpensive. It was (just) out of its pitiful one year warranty, but Australian Consumer Law demands that goods should last for a 'reasonable' time, and one year for an expensive TV is clearly not 'reasonable' by any definition. I managed to convince the manufacturer of this, and a couple of service technicians came to my house, made the same diagnosis I did (faulty 'main' board), and replaced it.

"What happens to the old board?" I asked. "Oh, it will be tossed away" I was told. No attempt is made to repair a faulty main board, even though it's likely to be a relatively easy fix with the right equipment to hand. I have no doubts whatsoever that if it fails again, I'll be told that the part is no longer available, so the rest of the TV either gets recycled, or I take it to bits to see if I can make something with the parts. The 'leftovers' will then be recycled. The main board has a microprocessor, many support ICs for the various inputs, the TV tuners (digital and analogue) and controls for the LED back-lighting assembly. And all that gets thrown away!

Compare this with (say) a 40 year old guitar amplifier. Whether it uses valves (vacuum tubes) or transistors, it can (and usually will) be repaired. The technician needs to be able to work out suitable replacement transistors for obsolete ones, and perform other repairs as needed. The required parts (except for transformers which are often available from specialist resellers) are generic, and replacements are easy to get almost anywhere (other than valves, but that's another story altogether). Anyone who's had to try to fix any of the 'latest and greatest' pro audio gear knows that it will be full of SMD parts, and may be difficult or impossible to fix without a board swap. I recently had a look at a PA speaker for a customer, and it was SMD from one end to the other. The Class-D power amps, switchmode power supply and even the preamp used only a small handful of through-hole parts. No schematics were available, and it was a write-off (and only a few years old). Pro-audio gear is often expected to last for decades, but that can't happen if the only fix is a board-swap!

As noted above, double-sided PCBs can cause problems for anyone not experienced with them. Unless you have a professional vacuum solder-sucker, the only safe way to remove parts is to cut their legs off first. Then you can remove one piece of lead at a time, and you don't have to try to de-solder a complete multi-pin IC to remove it. I used to work on computer boards that were built with TTL ICs only, and the processor wasn't an IC, it was a complete (and large) circuit board. These were not thrown away - we were expected to track down the faulty IC(s) and replace them (and none were in sockets). Even with the best de-soldering equipment available at the time, it was often nearly impossible to remove an IC intact. Cutting off the leads was the only way to ensure the multi-layer PCB wasn't damaged.

Modern production techniques make this approach unrealistic, unless one has access to proper SMD rework equipment. Few hobbyists can afford the equipment needed. Hot air rework equipment is only the start, as you also need a good electronic microscope (with a large screen), and if you can't get a schematic, then it's almost impossible to trace the circuit of a complex system to work out what everything does, and in what order.

I fully accept and understand that many of the things we take for granted today have to use SMD components. There is no way that a smartphone could be built using through-hole parts, and nor can many of the other things we use daily. However, it would be nice if one could buy a replacement PCB, rather than have to toss out the entire product when some tiny part fails. Sometimes you can get lucky of course, and many a switchmode power supply has been brought back to life by replacing electrolytic capacitors that have developed a high ESR (equivalent series resistance).

Some time ago (between 1999 and 2007), there were countless computer mother boards that were fitted with a bad batch of electrolytic capacitors (sometimes referred to as the 'capacitor plague'), and when they failed it was either replace the caps or replace the whole board. Many DIY people opted for the repair option, as did computer repairers. Fortunately, they were through-hole types, and while not exactly easy to remove, it was possible. Unfortunately, it's not always so obvious (the faulty caps bulged and/ or leaked electrolyte), and I'm sure that a vast number of otherwise perfectly good machines (with intact peripheral boards, power supplies, cases, fans, disk drives, memory etc.) would have just been tossed in the bin (or hopefully recycled). The waste of resources involved is enormous - time, energy and materials are simply scrapped.

This trend won't stop - it will only get worse. Some manufacturers make it almost impossible to even gain access to the electronics, with cases secured with a multiplicity of different screw sizes and head types, or with no visible means of access at all. To my mind, this is pure bastardry - it's done deliberately so you have to go to their outlets and pay well over market value for a simple repair. Of course, you can also do a web search and find detailed instructions or videos showing how to get the product apart, but we shouldn't have to do that. Having paid for the product, you own it! You don't own the intellectual property (so you can't just duplicate it and make your own), but you do own the physical 'good', and you should be given the chance to fix it yourself.

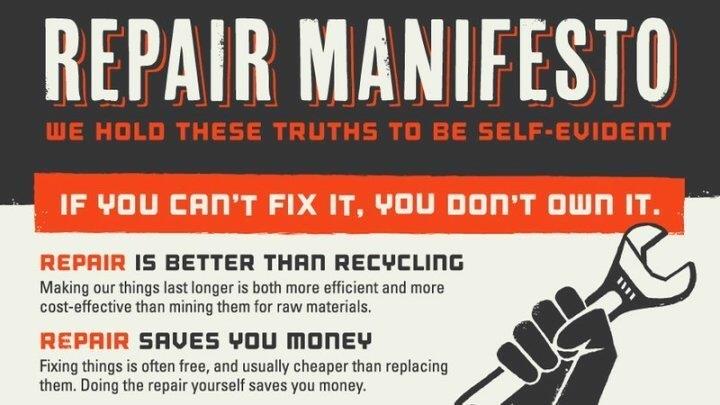

The 'Right To Repair Manifesto' (Click For Full Size Version)

You'll see the above all over the Net, and it needs to be spread even wider. People need to know about the movements that created the manifesto, just as they need to have the right to repair their own goods, or to choose who repairs them. No company or corporation should ever hold you to ransom, so they can charge $200 or more just to change a battery in a phone, or fix a problem that they introduced themselves with a 'software update' that went pear-shaped and bricked your device (i.e. permanently disabled it so it could not be used at all). These companies won't do anything to help their customers that isn't forced on them by legislation. They seem to forget that if it wasn't for their customers, they wouldn't exist! It's way past time to start treating buyers fairly.

Some manufacturers take the level of bastardry to new levels. One speaker maker (which shall remain nameless) offered customers a discount on a new system if (and only if) they used a supplier app that 'bricked' the product (rendering it useless). There isn't a single well-founded idea in this approach, and a great many customers were rightly incensed by the 'offer'. I'm sure that there would have been some people who took advantage of the 'service', but this is one of the most cynical (and wasteful) schemes that I've ever heard of. Consider that most of the speaker system was still perfectly alright (cabinet, loudspeaker drivers, power supply as well as the built-in pre and power amplifiers), and to render all of this into waste is (or should be) classified as criminal behaviour.

The 'I Fix It' (or ifixit) aka 'Right To Repair' movement is growing all the time, because there are a lot of people just like me, who think that we are entitled to repair stuff we bought, whether the manufacturer likes it or not. Some devices are simply 'built to be built', and are pretty much impossible to repair. This isn't good for high-cost items, but even cheap things should be able to be fixed if/ when they fail. Many hobbyists and others will fix a product themselves, even if it's not economically viable - I have, and I'm by no means alone.

Then there are the countless electronic products advertised on eBay, either as a complete system or a sub-assembly. Some of these have serious design faults that make them unsuitable for anything (and don't bother asking the seller for help), while others are quite good. Telling which is which from the description is usually not possible. You might get an idea from feedback, but the way that works on eBay makes it almost worthless. You have to buy it to find out if you bought a peach or a lemon. If it's the latter, getting your money back will often be 'challenging' (marketing-speak for 'impossible'). I shudder to think how much land-fill results from people buying 'cheap' goods on-line, only to discover that they are of no use to man or beast. It will almost always be made with SMD parts, and it's common for the suppliers to erase the IC part numbers so you don't have a chance to repair it - assuming that it can be repaired.

There are people all over the world who work out how to 'fix the unfixable', and they post videos on-line to show that it can be done, and how. In some cases they don't tell you very much (other than how clever they are), but there are many that explain in detail how to do anything from reprogram your car to accept a new remote, to how to dismantle various smartphones, tablets, laptop PCs, etc. The Internet has made so much knowledge available than we ever had before, but if you can't get the 'special' part you're still screwed. In some cases, the only way you'll get a specialised part is to remove it from a 'donor' device of the same make and model. Occasionally, a special level of bastardry is applied, by encoding ICs with an ID number that's unique to the device it cam from, and it won't work in anything else. This is not for your 'security' or any other bullshit they many come up with - it's to stop you from fixing it!

For a long time now, people have been collecting and repairing vintage electronics. Vintage valve radios are popular, and there are people who collect and repair guitar amplifiers and other 'old' electronics - including vintage test equipment. With the advent of SMD parts, this is often not possible, other than by people who have the equipment and (more importantly) can get the parts. A vintage valve radio is interesting and often beautiful. A vintage CD player is a different matter. Not only will it be difficult (or impossible) to get replacement components, but mechanical parts usually can't be built by a dedicated hobbyist restorer. An old radio generally uses a few simple mechanical parts that can be re-made in a well equipped workshop, but if a tiny plastic gear in a CD player breaks, the chances of making a new one are next to impossible. Clock-makers (or restorers) will likely have the equipment needed, but they are a dying breed (literally). Most have little or no knowledge of electronics, and while there are exceptions, they are uncommon. In case anyone was wondering, the tools for cutting gears and pinions are both highly specialised and very expensive. You need multiple cutters to handle the various 'modules' for different types of gears, and the cost can run to $thousands.

If you do come across old cassette, CD or DVD players that can't be repaired, consider removing the transport mechanism as a source of donor mechanical parts. You may or may not get what you need, but the parts can often be used for other things, and you might even get lucky. This leads to the next section ...

Recycling (at your local recycling centre) is far better than tossing electronics into the bin, where it ends up as landfill. However (and assuming that repair isn't possible), reusing as much as possible to build something else (re-purposing) is even better. Not everything can be re-purposed. In particular, printed circuit boards and metal parts that are designed for a specific purpose with dedicated components. Some of the larger parts (heatsinks, power transistors, MOSFETs, fast diodes and (perhaps) large capacitors) may be able to be removed intact, and it's not quite so hard if you don't have to preserve the PCB itself. Plated-through holes may come away from the board, but since the board is 'bad' anyway, it doesn't matter if it's damaged. Ideally, the remainder of the PCB should be recycled (to rescue the copper, tin, and sometimes gold) rather than thrown away, but this may not be possible.

It's very difficult to re-purpose switchmode transformers, because most are vacuum impregnated and can't be dismantled. In some cases you may find a solvent that will dissolve the resin, but any that work are usually toxic and/ or extremely flammable. These solvents also pose environmental risks, and pouring them down the drain is an offence and can cause significant damage to treatment plants in the waste-water system. Being environmentally aware is important - we only have one planet, and we have already caused it to change for the worse. Sometimes it will be possible to re-purpose a switchmode transformer, but it's tricky and you need the skills and equipment to be able to analyse it before you try to use it for something else.

The more chassis/ cases and parts that can be reused the better. DIY is generally the only way this can happen, and if you haven't read it, I suggest that you look at the article Why DIY, which explains the benefits of DIY (and contrary to belief, saving money is not the primary reason). In many cases, it will be possible to gather a few chassis (with transformers, heatsinks, etc.) when your local curb-side clean-up is in full swing. The things that get thrown away are often astonishing, and you may be able to gather enough bits and pieces to build your next project, at zero cost. I don't know if 'council clean-up' programs exist elsewhere, but in Australia they are fairly common, and typically happen twice a year. I know of a number of people who've benefited from this, and I must admit that I've 'rescued' a few items myself.

Many ESP customers use the PCBs they buy to replace the innards of old (and broken) amplifiers. The chassis, transformer, front panel and connectors can all be re-used, and in some cases the pots can be re-used as well (assuming they are high quality and still fully functional). Input switching may not require replacement, so by adding a preamp (and power supply for same) and a new power amp, an otherwise useless piece of kit can be rebuilt, often better than new. Even if the original front panel is no longer fit for purpose, if that's the only chassis part that has to be replaced then you are still well ahead. A great many amplifiers from the 1990s and later have digital displays, microcontrollers and other things that are all SMD, and usually cannot be repaired. By salvaging as much as you can, there's every chance that the amp can be rescued from the tip, with most of the expensive parts retained.

There are other things you can do as well. As an example, I recently came across a project to convert an old (4:3 ratio) LCD computer monitor into a high resolution microscope. This is on my agenda at the moment, and the only thing needed that I don't have is the spare time to put it all together and document it. Otherwise, the monitor will never be used again because (nearly) everyone now has a 16:9 ratio screen. This idea means that the monitor won't be recycled (there's not much worth saving inside), but it gets a new lease on life by doing something that would otherwise be costly to purchase as a dedicated product.

It used to be that white goods (washing machines, dishwashers, stoves (cook-tops, ovens, etc.) were either fitted with basic mechanical (clockwork) timers, electrically driven sequencers and/ or basic thermostats. Much the same went for refrigerators and air-conditioners, which had an electric motor, a fan or two and a thermostat, with not much else. Now, all of these are electronic, with mechanical sequencers replaced with microprocessors. Most new air-conditioners and fridges use an inverter to drive a variable-speed motor, and there are even fridges with a camera on the inside and an LCD screen on the outside so you can see inside without opening the door. While these can all make the appliance more 'desirable' (if you like that sort of thing), they also introduce multiple points of failure. The power supplies are now very complex as are the inverter drives which power the motors, rather than directly off the 50/ 60Hz household AC mains.

These latest home appliances are (usually, but not necessarily) more energy efficient than those of old, but how many will last long enough for you to realise an overall saving? The new 'machine' may save you $20 a year in energy costs, but if it costs only $200 more than an equivalent 'old technology' machine, then it has to last for ten years to break even. We all need to reduce our energy consumption, but the maths have to work as well (for us, the consumers). You can be sure that the maths will add up for the manufacturers and retailers, because a PCB is far cheaper to build than an electro-mechanical sequencer for example. There are people to this day who still have working washing machines that are over forty years old. Don't expect any modern appliance to even get close to that.

The home handyman used to be able to fix many basic faults, but now a breakdown usually means a board replacement. When boards are no longer available, the product (regardless of cost or age) is usually irreparable. Many of these items are seriously expensive, and having to replace the entire product because a PCB inside has failed is insane. The complexity of these items has risen dramatically, and often for no good reason. Fridges are still being tested and found to perform badly (some very badly), washing machines have caused house fires, and countless products that could be repaired are declared a write-off because no-one can fix the controller board.

The fault may be nothing more than a bad capacitor, but most ('company') service technicians won't even consider attempting a repair. If they have a replacement PCB, that will be fitted, and if not, you now have a large piece of scrap that you have to try to recycle. Some retailers may offer to take the old one away to be recycled (or possibly even repaired), but often you are just left to deal with it yourself. If service information were made available, it's likely that most of these goods could be brought back to life, and in many cases for only a relatively small cost. This is why the 'right to repair' is so important.

Now that new laundry appliances usually don't use conventional 50/ 60Hz motors, the inverter motors aren't quite as salvageable, but you can find new uses for the 'pancake' motors that are now common. There are several projects on-line that show how to convert the old motor into anything from a variable speed drive (their original purpose) to your own wind-turbine. There are other useful parts as well, especially solenoid valves and smaller self-contained pumps with motors. However, not everyone has a need for these items, and mostly the whole machine is recycled or dumped.

One thing that could be done (and usually very easily) would be to use an 'open-source' microcontroller. In many cases, everything needed could be done easily with an Arduino, which is a complete microcontroller on a board. A replacement can be bought for well under $20, and they are easy to program if the source code is made available. Interface boards (to drive solenoids, small motors, displays, etc.) are also available, but it's more likely that these would be proprietary. However, making the processing platform open-source would give experienced repair people an easy way to replace it if (when) it fails. The source code (program file) is never normally released, but it's not rocket science - most programs are fairly simple, and any manufacturer who did this would get some very positive (technical) press coverage, and would ensure that their product could be repaired for years to come. I strongly suggest that you don't hold your breath while waiting for this to happen!

The situation is getting worse all the time. Once we had cheap, easily replaced light bulbs/ globes that we knew would die, so a number would always be on hand to replace any that failed. They were terribly inefficient and gave out far more heat than light, but that wasn't always a bad thing in cold climates. Then we had CFLs (compact fluorescent lamps) which had comparatively complex electronics inside, and when these failed the home-owner was faced with a dilemma - the tube contains a small amount of mercury (a potent neurotoxin), and putting that in land-fill isn't a good idea. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of users have no knowledge of electronics or mercury, so failed CFLs were consigned to the bin (and thence land-fill).

Now we have LED lights, which have a much longer lifespan than a CFL but also contain electronics. In most cases of LED lamp failure, it's the electronic power supply that fails first - often well before the LEDs have lost any performance. The chances of repairing the power supply (or having it repaired) are next to zero, and it would cost more to fix it than to buy a new one. Few people understand that there are any electronics involved, and when it dies, it goes in the bin. Even most recyclers won't take LED lamps, even though they are electronic devices and have recyclable materials inside the impenetrable case. Yes, it's important that most people are kept out because they may end up killing themselves or someone else, but the waste of resources is huge.

For lighting products, it doesn't help that most new luminaires (light fittings) do not consider ventilation. This is essential for any lamp that contains electronics, because over-temperature reduces the life of all components, especially electrolytic capacitors. To keep making fittings that are unsuitable for the lamps that will be used in them is madness, and the majority of householders are unaware that modern electronic lighting products should be kept as cool as possible. Don't expect any info on the packaging (which no-one reads anyway), because it's not there for any that I've seen. Predictably, this adds to the waste stream, because the lamps don't last as long as they should.

At least most industrial LED lights (warehouse, factory, street lighting, etc.) use modular assemblies, and many are designed so the power supply can be replaced as a separate unit, and the LED units are often modular as well. Various parts of the fitting can be replaced individually, so the entire unit isn't discarded after a failure. These high-power units generally have substantial heatsinks and many other parts that can be recycled when the product reaches its end-of-life. Since most will claim 30,000 hours or more (10 years if used 8 hours/ day), these remain one of the most friendly upgrades around. Compared to metal-halide or mercury-vapour lamps, they provide more light while using around one-third the power. This can save the owners vast amounts, both in power consumption and maintenance costs.

In some cases, 'products' are made, sold (or given away) that should not exist. An example is shown below, and it's a 'universal' AC adapter for US, Euro or UK plugs to fit Australian 'power points' (Mains outlets). The adapter in question has a little sticker that states "For Export Only" along with some Chinese writing that presumably says the same. One can surmise that these would be considered illegal in China, but export is ok. Are they trying to kill us? These 'travel adapters' have a CE mark, but they will not be approved by any agency/ authority in any country. The internals are extremely flimsy, and all connections (and especially the earth (ground) connection) are likely to be intermittent at best, or fail to make contact at all! The earth connection is a special worry, but all connections rely on rather tenuous contact pressure that will not meet even the most relaxed standard. The metal used is far too thin, and has insufficient 'spring' to ensure consistent contact pressure. At high current (they are supposedly rated for 10A), I'd expect serious overheating with the possibility of fire.

What a Waste of Materials!

This is a waste of everything that went into making it. Injection moulded plastic, formed metal, and screws that hold it together. To make matters worse, if a child fiddles with it, the earth pin of an Australian, US or UK plug will happily fit into any of the openings on the front, including the active (live) socket!. There isn't a regulatory agency on the planet who will approve these for use (they are made with many different connections to suit most countries' mains outlets). It goes without saying that if you have one (or more) of these, they must not be used. If someone is killed or injured because you use one (regardless of their lack of understanding or even plain stupidity), you are responsible for their death or injury and it could cost you dearly, both in remorse and financially.

This is just one example, but there are plenty of other products that are either unsafe and/ or dangerous, and people buying from eBay or similar become the importer. As such, you are responsible for the consequences. If anyone sold the travesty pictured in Australia they would be penalised (and the fines for 'distributing' unsafe and/ or dangerous products can be financially crippling). These are both unsafe and dangerous. If you have anything similar, it should be destroyed. Recycling is unlikely, so it's a 100% loss of the resources that went into making it in the first place.

Personally, the idea that anyone would make and sell such a dangerously ill-conceived design is terrifying. That they exist in countless households worldwide should also be terrifying, and I urge anyone who has any to dispose of them forthwith. More bloody landfill, for something that should never exist in the first place!

One of the latest trends is home-automation, which uses a mix of proprietary equipment which is made by only a few major manufacturers, and cheap add-on gear from China. The codes might be 'open-source' in theory, but try finding any specific details and you will be disappointed (to put it mildly). While these IoT (internet of things) innovations can improve your quality of life, you must also be careful to ensure that equipment that uses your home wi-fi network doesn't provide an easy point of ingress into your local network. No-one wants their computer infected with a virus or 'back-door' application that allows criminals to access personal files.

Another thing you'll be hard-pressed to find is the power consumption of some of the equipment on offer. Many (most?) can be expected to draw around 1-5W, and they are usually powered 24/7. If you know the power (or can measure it), it's easy to add up all the devices in use. You may be surprised at the total, and with only ten devices, each drawing 5W, that's 50W/h (0.05kW/h) - it's like leaving a 50W lamp running 24/7. The cost is not great, but it still adds to your power bill. Unless these devices are all built to the relevant standards, there's an ever-present risk of fire should one fail. They are almost always made using SMD, and clearance distances may be below the recommended limits - at least 5mm between hazardous voltage (the mains) and the low voltage used for the device (typically 5V DC). Check what you have, and ensure that it has clear indications that it complies with the safety standards that apply where you live.

One thing we don't know for certain (and the makers won't give a straight answer) is how much normal conversation is picked up and sent to the manufacturer's data system. There have been claims that some (allegedly) 'anonymous' data are sent for accuracy testing, but each and every device that connects to the internet via your modem has an IP (internet protocol) address, and this can be used to find your exact location. It may require a search warrant and 'cause' to get it from the ISP, but it's there for anyone who has a right to get it (or hacks the system to obtain it). While this is 'off-topic', it's still something to consider before you entrust your privacy to large corporations that collect your data with ever-increasing voracity.

You may well ask what the IoT or IIoT (Industrial Internet of Things) has to do with anything. That's easy to answer - most of the IoT devices for home use are designed to be thrown away when they fail, with no consideration whatsoever for service later in their life. Expect everything to be glued together, with nary a screw in sight (not even concealed under little plastic feet). I was given just such a device by a friend, and it's designed not to be opened at all. Obviously, anything can be opened, but it will probably look dreadful after it's been cut apart, and it may be designed specifically so that any attempt at opening it will destroy something inside. It's quite understandable that wall supplies (aka plug-packs/ wall-warts) will be sealed, because if someone tampers with the innards it's easy to create a potentially fatal fault. The problems come about when the entire product is made unserviceable, and it's usually deliberate.

The IIoT is now being pushed by multiple vendors, with systems that monitor every detail of a machine's operation, and raise an alarm if something goes wrong, or starts to behave abnormally. In theory, this is good, as it can save a machine from a major failure and ensure that an out-of-spec part is replaced before any damage is done. However, there have been stories in engineering newsletters of many IIoT devices being insecure, with some providing no option for installing new, more secure code. These devices are then just so much more scrap, adding to the wasted resources. The scope for infiltration and the ubiquity of these devices should scare people away, but it seems that either no-one cares or they have an "it won't happen to me" attitude.

The range of devices increases daily, with new announcements published in engineering newsletters, on the manufacturers' websites and advertised elsewhere. Wi-Fi mains switches (amongst many other 'gizmos') are readily available from auction sites and various other outlets. How many have been certified by the relevant authorities? Most will claim certification with Australian/ NZ Standards, British Standards, UL, CSA, VDE, etc., but many will never have seen the inside of a certified laboratory, let alone been tested in one. There is (almost) certainly a place for these 'new-fangled' devices, but not if they are unsafe and/ or can't be repaired. Most will fall into the second category, and anything cheap will likely be in the first. Throwing away entire sub-assemblies because one small part has failed isn't the way to protect what's left of our planet, and installing unsafe products can have devastating consequences.

The environmental impacts of the 'throw-away' mentality are difficult to assess with any reliability. Some items are shipped off to 'third-world' countries where they are pulled apart and all usable materials extracted. The techniques used are often dangerous, with hazardous chemicals employed, and residues just dumped on the ground or into creeks or rivers. Ultimately, the very earth upon which we depend is polluted with chemical waste that can cause serious health problems. There's plenty of evidence that shows the effects of plastic pollution, and plastic is one of the most common materials for enclosures for many electrical/ electronic products. Very little of that gets recycled. The EU probably has the most stringent regulations for recycling, but most other countries are well behind, often with little or no indication that anything will change.

For anyone who doubts the idea of 'climate change', we don't have to go back very far to see that humans can (and do) cause damage on a planetary scale. Younger readers will not have used CFCs (chlorinated fluorocarbons or chlorofluorocarbons), because their wide-spread use was banned internationally in 1987 due to their ability to break down the ozone (O3) layer. This is situated in the upper atmosphere, between 15 and 30km above the earth's surface. The decomposition of ozone eventually lead to a 'hole' in the ozone layer above Antarctica, and has increased the level of UV (ultraviolet) radiation reaching Earth. This has impacted Australia, where we (along with our neighbours across 'the ditch' in New Zealand) have the highest number of skin cancer sufferers on earth (per capita). Whether this is actually due to ozone depletion is subject to some argument, but the point is that we humans invented a way to damage the ozone layer - which is a long way from the earth's surface and huge!

One of the first CFCs was trademarked 'Freon', and it was used extensively as a refrigerant gas (in fridges and air-conditioners), as a solvent, and as a propellant for pressure-pack spray cans. It is highly volatile, non-flammable and was thought to be completely safe, but history shows that was not the case at all.

We also see new evidence on a regular basis concerning plastic waste, but we don't see a concerted effort to make significant changes. Many local government districts worldwide do provide plastic recycling facilities, and new techniques are seeing many plastic materials (as well as motor vehicle tyres) being remanufactured into new products. This has to continue, but it needs effort from us all to ensure success in the long term.

We have proven (with CFCs and plastics) that humans can impact the environment as a whole, and on a grand scale. To deny that other activities (vastly more prolific than the manufacture and use of CFCs) can cause damage is burying one's head in the sand. The science may not be to everyone's liking, but it's pretty much beyond argument for the most part. Ultimately, it doesn't even matter if we have caused 'climate change' or if it's something that just happens on an irregular basis. The simple fact is that we can't keep doing what we've always done, and we need to change. Plastic pollution is now a serious problem, and a great deal of that is due to 'single use' items. It makes no difference if it's a plastic bag or a mobile phone - throwing it away just doesn't make sense.

DIY has an important place here. The average amateur (whether an electronics enthusiast, woodworker, metal fabricator or motor mechanic) is far less likely to throw things away if they think they will find a use for it later. This often leads to an inordinate amount of 'stuff' stashed away in the garage or a spare room, but much of it will be reused. Murphy's Law dictates that you will need something you threw away within a few days of doing so, so many people (including [or especially] me) tend to amass a great deal of 'spare parts'. For what it's worth, many of them do get reused or re-purposed, and anything that can't be reused is recycled (I'm fortunate that our local recycling centre is only ten minutes away).

We all need to do our best to ensure that we waste as little as possible. Industries have been created around this principle, and 'reverse garbage' centres have popped up all over the world so that perfectly serviceable 'scrap' materials can be bought cheaply and reused. You can participate by donating unused materials, and/ or by buying materials from these centres. Unfortunately, most don't seem to deal in electronic goods, but you might get lucky. One of the best things about DIY is that people are more likely to fix something they built, because they have a personal stake in its creation. The same can't be said for a $20.00 Class-D amplifier, purchased on-line, that fails or doesn't work.

It's a side-issue, but the man who invented CFCs (Thomas Midgley Jr.) was also responsible for another banned product - tetraethyl lead (TEL). This was used in petrol ('gasoline') from the late 1920s until between 1989 and 2006 (depending on locality). TEL was added to petrol to improve its octane rating, and to reduce valve seat wear by 'lubricating' the exhaust valve seat. Modern engines use hardened valve seats and new methods of petrol production have made TEL redundant. Thomas Midgley also invented a lot of other things, but he's especially remembered for CFCs, TEL, and for the way he died [ 7 ].

The issues described here aren't limited to electronics. Once, anyone with a few decent tools could perform a service on their own car, and undertake many repairs. Today, independent service centres and your local mechanic may be hard-pressed to be able to get even the most basic information they need to service a modern car. It's riddled with electronics, and diagnosis often relies on proprietary software that can read and decode the error messages that are obtained from the OBD (on-board diagnostics) port hiding under the dashboard. Court cases have been held all over the world to force manufacturers to release essential diagnostic information. Some have succeeded, while others have paid lip-service to the court demands and made only rudimentary attempts at transparency. This makes it almost impossible for the home mechanic to achieve very much, because even if the details are made available to mechanics, they are usually not available to the 'general public'.

Governments worldwide have been slow or even reluctant to consider legislation that would force manufacturers to make service information available. There is some sign of progress in the USA, but many other countries (including Australia) have shown no real signs that they are willing to stop monopolistic practices. Australian Consumer Law (ACL) has some influence and there are a few safeguards in place so far. There is also a move to consider thinking about maybe doing something more  . However, it's well past the time for what can best be described as 'idle chatter' and actually pass laws that make it illegal to prevent people from servicing their own equipment. You own it, and have the right to pull it apart if you want to. Some (rather large, and you probably know who they are) corporations don't want you to do that, and will try anything to stop legislation that forces them to provide information and spare parts.

. However, it's well past the time for what can best be described as 'idle chatter' and actually pass laws that make it illegal to prevent people from servicing their own equipment. You own it, and have the right to pull it apart if you want to. Some (rather large, and you probably know who they are) corporations don't want you to do that, and will try anything to stop legislation that forces them to provide information and spare parts.

There is no longer a place for so-called 'planned obsolescence' and while it can be argued that it's a myth, that's not strictly true. All electronic components are subjected to electrical stresses when in operation, and some are notoriously unreliable. Remember the 'capacitor plague' mentioned above? Electrolytic capacitors have a typical rated life of only 1,000 to 2,000 hours when used at the rated maximum voltage and temperature. Most will beat that easily in use, but if powered 24/7 in a hot environment, a lifespan of less than one year is quite possible (and I know this from personal experience). When the item concerned is deliberately made so that it's uneconomical to repair it, then it's just more landfill and wasted resources. Who would spend up to thirty minutes fixing a LED tube (fluorescent replacement) that costs $20.00? I will, and I've done so. Mostly, the replacement part costs less than $0.10 or so, but more importantly, perfectly good aluminium heatsinks, a board full of LEDs and the outer casing are all reused with only one tiny component sent to the tip.

The above is an 'extreme' case - it's not worth anyone's time to spend 1/2 hour to repair a $20.00 LED tube, but in my case it was largely to find out why these tubes kept failing. Use of a 1µF 450V electrolytic capacitor turned out to be a poor design choice, as these small, high-voltage caps are notoriously unreliable. A 10 cent part makes a $20 LED tube unusable, often within the warranty period. How does anyone think that's a good idea? Unfortunately for consumers, this is not an uncommon problem. No 'normal' consumer will attempt a repair, so everything that went into making the item ends up as scrap.

Main Index

Main Index Articles Index

Articles Index