|

| Elliott Sound Products | Crossover Distortion |

Main Index Main Index

Articles Index Articles Index

|

In a number of articles I've explained that negative feedback can never eliminate crossover distortion. The simple reason is that at low amplitudes, an amplifier with crossover distortion has no gain, and without gain there is no feedback. The problem is that this is probably not immediately intuitive, so the issue is looked at more closely here.

Rather than make a simple assertion (however true it may be), it's necessary to prove the hypothesis. This is fairly easy to do, and it can be done with real circuitry or simulations, with results that will be almost identical. This makes it easy for anyone to duplicate the results.

There are actually two problems, not just one. Almost all real amplifiers have less open-loop gain at high frequencies than they do at low frequencies, and this is due to the compensation capacitor (aka Miller cap). The combination of lower gain and inevitable reduction of transistor gain at high frequencies means that distortion rises with increased frequency, even if there is no crossover distortion as such.

It's worth pointing out that if an amplifier is being used to control a motor (other than a loudspeaker driver) or other non hi-fi application in an industrial controller or similar, a tiny bit of crossover distortion is not an issue. True Class-B operation is common in these systems, as it minimises quiescent current, and the 'dead band' created by the crossover distortion is so small that it doesn't affect operation. It's only when we look at 'proper' audio circuits that it becomes a problem that must be solved.

Almost without exception, hi-fi amplifiers are Class-AB, meaning that they operate over a small range in Class-A, with both output devices conducting. The idle or quiescent (no signal) current is generally within the range from a few milliamps up to 50 or 100mA in some cases. There is almost always a thermal feedback mechanism in place to keep the quiescent current stable, as the emitter-base voltage falls as the transistors' temperature increases. In some cases the bias is held constant with diodes attached to the heatsink. Transistorised versions (commonly known as bias servos) are the most common, with the temperature of the output devices (or driver transistors for a Sziklai pair) sensed to maintain stable current. In the simplified circuit used here, a floating voltage source is used, and emitter resistors keep the current reasonably stable.

The problem is actually more complex than it appears. Transistor gain falls as the current is reduced, and this means that there will always be some non-linearity as the signal passes through zero. Class-A amplifiers get around that by conducting for the full waveform cycle, at the (great) expense of high continuous current and very low efficiency. Most modern amplifiers have levels of crossover distortion that are negligible - it's still there, but is usually well below audibility at any listening level. If you measure an amplifier and look at the waveform of the residual (distortion + noise) from a distortion meter, it's easy to recognise crossover distortion. Rather than a smooth waveform consisting of low-order harmonics, you'll see a spiky waveform with a high peak-to-average ratio. It's worth connecting an amplifier to the output of a distortion meter so you can hear it. If it sounds nasty, then it is nasty.

The first test circuit uses a pair of medium power transistors, BD139 (NPN) and BD140 (PNP) and these will be used for most of the examples. With ±12V supplies, 10Ω emitter resistors are included, but these make no difference if the transistors have no bias. The emitter resistors are only needed to stabilise the quiescent current in later tests where the transistors have bias, with the intention to eliminate (or at least reduce) crossover distortion.

The circuits used are all nominally unity gain, but without any bias this is reduced. The zero-bias condition can result in a gain of between -1.1dB and -80dB, depending on input level. The tests will use an input voltage of between ±14mV (10mV RMS) and ±8V (5.66V RMS).

The first test uses the transistors with zero bias, and an input of 5V RMS. The test circuit is designed for simulations, and includes things that are a little irksome to incorporate into a bench test. This is primarily due to DC offset, which can be very hard to remove in a 'real' circuit. It's possible to add a servo circuit, but that adds complexity that's hard to justify.

The circuit for the tests is shown below. Some of the devices (particularly voltage sources) are 'ideal', in that they have zero impedance. This has been compensated for by adding an opamp, which can be configured as a buffer or within a feedback loop. The circuit is deliberately very simple, and the 4558 opamp is adequate for use with feedback. For many tests, it's just a buffer. You can use any opamp you like - it's not critical.

There's a switch to connect the bias voltage (shown as a battery) and another to turn feedback on or off. The circuit operates with (nominal) unity gain at all times, but without bias this is not possible because there can be no output until the input exceeds the base-emitter forward voltage. The opamp can be anything you like (including a simulated 'ideal' model), and in this circuit it makes virtually no difference whatsoever. C3 is used only to remove any offset that may make the output unpredictable, and the 100Ω load ensures that the transistors have to pass some current. If that's omitted the results are not useful.

If we apply an input of ±14mV (10mV RMS) to the circuit (bias switch off), the output is 435nV (yes, nanovolts) RMS, a 'gain' of -87dB. This isn't exactly zero, but it's such a low gain that assuming zero gain is pretty close. Applying bias, the gain becomes -250mdB (0.25dB), and this is what we normally expect from a voltage follower. With the zero gain case, applying feedback will reduce the distortion, but even with an overall gain of (almost) unity and ideal parts throughout, the distortion is not zero!

The current source is used for the tests performed in the 'High-Impedance Drive' section below. The point marked 'A B' is opened, and the current source connected to the base circuit of the transistors. This is (close to) the way output stages are normally driven within an amplifier circuit. It's easy to do in a simulator, but less so in a bench test. The current source needs an internal impedance of at least 1MΩ, so a source voltage of ±100V could be used with a series 1MΩ resistor connected to 'B' will provide ±100μA base current. This will work, but is somewhat impractical.

The 1Ω emitter resistors mean that even if the transistors really were unity gain, the maximum output is 990mV/ V. This is not a limitation, and when feedback is applied that compensates for the small loss of gain anyway. The main thing is that the circuit is a simple emitter-follower output stage, albeit low power. The behaviour can be used to predict that of a 'full' output stage will do, either Darlington or CFP (compound feedback pair, aka Sziklai pair). It's easily constructed if you wanted to run bench tests, and the 1.3V supply can be a 1.5V cell plus a paralleled trimpot to adjust the voltage, as shown in the inset. Adjust the trimpot for about 5-10mA through Q1 and Q2. R1, R2, C1 and C2 ensure that the input is DC coupled, ground-referenced, and has a low impedance for AC.

As you can see, the red trace is at close to zero volts peak (616nV peak), so the circuit effectively has no gain. We can calculate the 'gain' of course - it's about -87dB. Not quite zero, but close enough. When bias is applied, the output increases to 13.6mV, so only 0.4mV has been 'lost'. This is because of the emitter resistors, and the gain of an emitter follower is always slightly less than unity - typically about 0.99 but it varies with the current.

The main test is at an input of 7V peak, and without bias the output is 6.2V peak. There can be no output until the input exceeds the base-emitter voltage for Q1 or Q2, so we see that 0.8V has been 'lost'. The distortion measures 5.73%, as shown in the graph. Applying bias (about 6.2mA) reduces this to 0.098%. These figures are without feedback. The performance with bias is respectable, and it can be reduced further by applying feedback. Without bias, the performance with or without feedback is unacceptable.

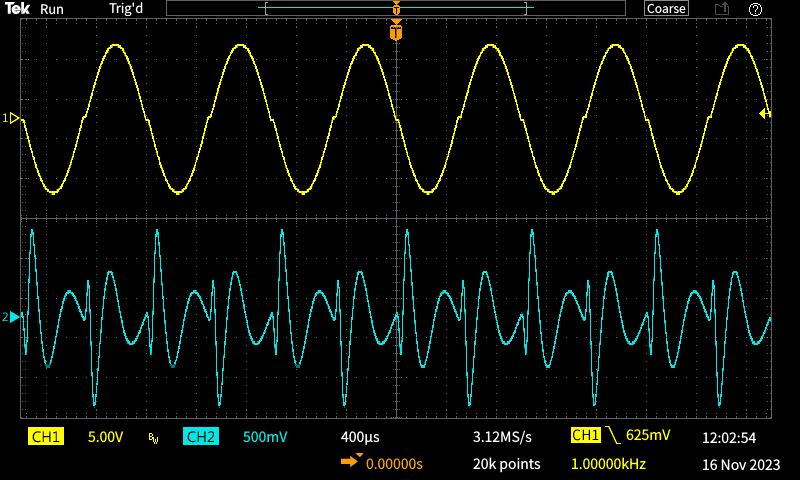

The distortion waveform of the 7V peak output without bias is shown above. This is the output from a 1.8kHz, 10th order high-pass filter (60dB/ octave), so only frequencies that are greater than 1kHz are seen, with the fundamental removed. This is what you'll see at the output from a distortion meter that uses a high-pass filter instead of a notch. I used this so the simulation and scope trace are reasonably consistent. The spiky nature of the waveform is immediately obvious, although this is an extreme example. In case you think this is an exaggeration, I ran the same test and measured the result - it's almost identical. The peak level is different because the distortion meter has an internal gain of two for the distortion output.

The input was 7V RMS for the bench test, and where we should see a 9.9V peak output (yellow trace) it's only 9.31V peak, and around ±590mV has been lost because there's no bias. The distortion meter measured less than the simulator, at 3.8% (the simulator says 4.7%). This is neither here nor there of course, as it's quite unacceptable. Why are they different? Almost all distortion meters use an average measurement, RMS calibrated, but the simulator uses 'true RMS'. The wave shape of the distortion (blue trace) is almost identical to the simulated waveform. The spiky nature of the waveform is easily seen, and shows the presence of high-order harmonics. Even though feedback can reduce the low-order harmonics, due to reduced gain at higher frequencies, the high-order harmonics cannot be reduced effectively. It's clearly impossible for feedback to eliminate the crossover distortion, as that would require a feedback circuit with infinite open-loop gain.

Note: If you look at this the wrong way, it can appear that feedback has increased the high-order harmonics. However, the real issue is that the feedback cannot reduce the high-order harmonics because there's not enough of it. The internal gain reduction of the opamp due to its dominant pole means there's less feedback at high frequencies, so more distortion components can get through (relatively) un-attenuated. By themselves (no FB) the harmonics should decay in an orderly manner, so referred to the 3rd, the 5th harmonic should be -4.9dB , the 7th at -8.4dB, etc. With a 6dB/ octave open loop gain rolloff, the decaying relationship no longer applies, and you can see harmonics at almost equal levels over a wide range (as much as two decades of frequency).

If 100% feedback is applied without bias, the 7V peak output distortion falls to 0.055% (optimistically), and rises to 0.43% at 10kHz. Why? Simply because the opamp has 20dB less gain at 10kHz than it has at 1kHz (internal compensation causes a gain reduction of 20dB/ decade or 6dB/ octave). I haven't shown graphs of this, because distortion below 1% is not visible on the waveform, and this also applies to an oscilloscope display.

At 20kHz the distortion has risen to 1.08% because there's another 6dB drop of open-loop gain from the opamp. You may have expected that the distortion would double (to 0.86%), but it's worse than that. 'Real' amplifiers are no different in this respect.

The important thing is that the gain is not almost zero when bias is applied. By applying bias to the output transistors, they can conduct even with the smallest input (all the way down to ±1nV or less). In reality you won't be able to measure any signal that small, as noise will dominate any reading. 1nV is -180dBV, easily done in a simulator but not in real life. The output is supposed to be a perfect replica of the input waveform, but as you can see, this cannot be the case with no bias. Too little bias means that the transistors are operating with less current, so their gain falls. If the bias voltage is reduced to 1.1V, quiescent current falls to ~170μA, and the output voltage with 14mV input is reduced to about 8.5mV. With an 80mV peak input, the distortion is a rather unimpressive 1.8%, with only 50mV peak output.

The internal emitter resistance (re or 'little re') for a transistor is generally taken to be 26 / Ie (in mA), so with 1mA re is 26Ω, rising to 152Ω at 170μA. It's not a fixed quantity unless the emitter current doesn't change, but with a quiescent current of a few milliamps the change of re (Δre) becomes less of a problem. Clearly, if re is significant compared to the load impedance, the output must be distorted - even with bias!

Fig. 1.6 shows that an 800mV (peak) input can just turn on the transistors, with absolutely gross crossover distortion (57.9%). Just applying 9mA bias is enough to reduce that to 0.008%, which would generally be considered quite acceptable for any amplifier. If feedback is applied, the same two tests show distortion to be 0.17% (no bias) and 0.0005% with bias.

Even though 0.17% could be considered acceptable (in some quarters at least), in this instance it's made up of many harmonics, ranging from the 3rd up to very high frequencies. The residual waveform (as seen at the output of a distortion meter) is nasty, showing significant spikes at the crossover points. The RMS value of the residual may only be 2.84mV as measured from the next waveform, but it invariably sounds worse.

As the level is reduced, the distortion increases. This is characteristic of crossover distortion, and at 80mV input, the distortion has risen to 1%, and it's over 5.5% with 8mV input. We normally expect to see the THD+N (distortion plus noise) to rise at low levels, but this should be due to noise alone. The distortion from most circuitry falls with reduced level. Fig. 1.4 shows the significant crossover distortion at 14mV (peak) without bias, and it requires no magnification to be seen easily.

THD measures 3.39% without bias, falling to 0.00054% with bias. The latter is quite acceptable, but that's only at 1kHz. We need to look at performance at higher frequencies too, or it's too easy to miss something that proves to be a problem during listening tests. 10kHz is a reasonable figure, even though the 2nd harmonic at 20kHz will not be present, and the first 'real' harmonic will be at 30kHz, well out of hearing range. However, any distortion will create intermodulation products, and these almost certainly will be audible.

Fig. 1.8 shows just how bad this can be. The conditions are the same as for Fig. 1.7, but the frequency has been increased to 10kHz. The unbiased output is beyond revolting, with a distortion of almost 20%. Once the output transistors are biased, the waveform is greatly improved, with distortion reduced to 0.26%. This isn't wonderful, because the opamp is running out of 'reserve' gain at 10kHz. If I substitute an 'ideal' opamp, the distortion is reduced to 0.0005%, because its gain remains constant with frequency. Unfortunately, you can't buy an ideal opamp.

There's another way to reduce the distortion in an output stage before feedback is applied, and that's to use a current source to drive the output devices. The opamp is disconnected at the 'A B' point, and the current source (shown in Fig 1.1) is connected to 'B'. Almost every amplifier made uses this technique, and it helps to overcome non-linearities, including crossover distortion. It's not a panacea though, as we shall see shortly.

It's somewhat harder to model with a simulator, and much harder to perform a bench test, because we expect signal sources to provide a voltage, not a current. Of course they do both when driving a load (the test circuit), but the impedance is low (50 or 600Ω for most instruments).

If the voltage drive from U1 is changed to an AC current source with an impedance of 100k, we can drive the output stage with ±1mA to obtain a peak output of about 7.3V with no bias. Under almost identical conditions otherwise, voltage drive (red) has a distortion of 5.7%, reduced to 3.4% with current drive. That's a fairly significant reduction by itself. Unfortunately, applying bias current doesn't help, and actually makes the distortion worse (3.73%) with high-impedance drive.

This is overcome in 'real' amplifiers by ensuring that the current source can deliver at least 5 times the peak current expected by the output stage. The primary reason for the constant current used in the voltage amplifier stage (VAS, aka Class-A driver) of an amplifier is not to overcome output transistor non linearities, but to get the best possible linearity from the VAS stage itself. Expecting the high-impedance drive to overcome the 'dead band' is unrealistic, and it doesn't work. It helps, but bias current is still required.

That the high impedance (current source) can help to linearise the output stage is a small bonus, but not the primary reason. The constant-current source may be active (using one or more transistors) or passive, using a bootstrap circuit. There is no significant difference between the two, but the passive bootstrap circuit remains my personal favourite.

It's not intuitive as to how high-impedance drive can overcome (at least to an extent) the dead-band created by an unbiased output stage.

The red waveform is the output, when the circuit is driven by a ±100μA current. It looks alright, but the distortion is still 3.75% (the inset shows crossover distortion). Of more interest is the waveform at the input of the stage (base drive). It has near-vertical sections as the current tries to remain constant, so the input voltage 'jumps' from one base-emitter offset to the other. The near-vertical sections jump from (about) -500mV to +740mV (positive-going) and roughly from +500mV to -650mV (negative-going) - it's slightly asymmetrical. Unfortunately, this process is imperfect due to other non-linearities in the circuit.

Ultimately, applying bias to an output stage is the only way to minimise crossover distortion. Without it, neither high-impedance drive nor vast amounts of negative feedback can overcome the dead-band, where the stage has zero gain. Even if the gain only falls a bit (say by 6dB), that means there is 6dB less overall loop gain at that point. Any reduction of distortion is proportional to the amount of feedback, so if the open-loop gain is reduced, so too is feedback. That means the distortion must increase.

The primary point of this short article is to demonstrate that feedback cannot work when a circuit has no overall gain. This point is rarely mentioned. There's another form too, which has been called 'secondary' crossover distortion [1]. This can be caused by old, slow power transistors, and is created as the transistor(s) fail to turn off cleanly. Most early power transistors were inherently slow, and turn-off behaviour is dictated by the speed at which electron-hole pairs can return to their quiescent state. Any transistor takes a finite time to turn on, and (usually) a longer time to turn off again.

At high frequencies (e.g. 20kHz) this can still be an issue, as the transistors have a degree of cross-conduction (i.e. both upper and lower transistors conducting). You'll often see the current demand of a power amp rise as the frequency is increased, and that's the reason. If taken to extremes, many amplifiers (even today) will fail if you try to obtain full power at 30kHz or more.

The BD139 used in the experiments will turn on in about 54ns, but it takes 140ns for it to turn off again. If we assume the same for the BD140 (usually unwise, but it will do for this explanation), there's a period of around 90ns when both transistors are conducting. If the output stage is driven at a high enough speed (with a fast squarewave), the extra dissipation can cause device overheating and failure.

If the Fig. 1 circuit is driven with a very fast squarewave (±8V, 1ns rise & fall), the peak collector current will exceed 250mA (the load only draws ±80mA). Bigger transistors are inherently slower. This is partially solved by using MOSFETs because they can switch much faster than BJTs, but they are also more nonlinear.

In Class-D MOSFET power amplifiers, there's always a 'dead-time' where both switching devices have no gate drive. This prevents so-called shoot-through current that can cause catastrophic output stage failure.

Please note that this article is not intended to demonstrate the optimum bias current, determine the 'best' output stage topology, optimum transistors to use or any of the other esoteric things that are discussed endlessly elsewhere. The only point is to demonstrate that negative feedback can never eliminate crossover distortion, because if both driver/ output devices are turned off, the circuit has no (useful) gain.

That doesn't mean that issues such as gm doubling (when both transistors conduct) and other issues are not important, but it also has to be considered that very few modern amplifiers have any audible crossover distortion. Eliminating all distortion is simply impossible, but once it's all below audibility further improvements are academic. There are many designers who strive for the lowest possible distortion at any level or frequency, and this is a worthy goal. However, it doesn't mean that the end result will be accepted by all as the ultimate, even if it's flat from DC to daylight and has distortion that's too low to measure at any level or frequency.

We can now get opamps with distortion at vanishingly low levels, so much so that 'trick' circuitry is needed to even measure the distortion. That doesn't mean that everyone loves them though (many people will still complain of 'poor bass' [for example], which is simply impossible as all opamps work perfectly to DC). It's the same with output stages, which are generally well behaved as long as decent transistors are used, ideally with the flattest gain vs. current possible. However, few (if any) power transistors will maintain their gain at the highest and lowest currents encountered in any amplifier.

Omit a decent bias servo at your peril with most amps, especially those using BJTs or switching MOSFETs (not recommended for linear operation, but that has never stopped anyone). Getting the bias current right is one of the most important things you need to do with any amplifier, lest you fall into the 'zero gain' issue described.

Main Index Main Index

Articles Index Articles Index

|