|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 234 |

Main Index Main Index

Projects Index Projects Index

|

This is probably the simplest project I've ever published, and it came about because I had a precision 10-turn pot with a vernier left over after building Project 232. In its simplest form it's just a pot, but that's too limiting. By including a rotary switch (or toggle switches), you can achieve any resistance between around 100Ω up to 100k. All fixed resistors are 10k, and with the 10k pot, you can set the resistance very accurately. This really is a precision device, with the ability to set the resistance within a few ohms over the range from less than 100Ω to 100k or 80k with the 'compact' version.

In theory, the vernier lets you read the resistance directly, but that depends (to some extent) on the pot's linearity and the vernier itself. Ultimately, you'd use the substitution box wired into your circuit and adjust the pot to get the result desired. Note that the recommended pot is 10k, 2W, and it can pass a maximum of 14mA. This is not increased just because the resistance is set to a low value. While the current is limited, it's quite satisfactory to use with most circuits you'll need it for.

The pot and vernier are shown below. I got mine from eBay, and while this is something I generally suggest that you don't do, there was no issue at all with either of the devices. There was a considerable wait because they came from China (where else?), but they were significantly cheaper than 'name brand' pots and verniers sold by the major distributors. For example, an almost identical pot can cost from AU$30 to AU$50 (some are even more expensive), and the vernier dials start at AU$12, with some costing almost AU$200. This isn't viable for most hobbyists.

I tested the linearity, and it's very good. The pots are branded 'BOURNES' but I don't know if that's genuine or not. Given that many manufacturers get their stuff made in China anyway, it's certainly possible that they are the 'real thing'. Either way, I've tested them extensively and found nothing to suggest that they are inferior in any way. The vernier dial is quite usable - it's not perfect, but it works well enough for a project like this.

As you can see, there's not much to it. The usable range is from about 100Ω - that really is the sensible lower limit, because a 10k pot (even multi-turn) gets rather touchy at very low resistances. As shown it extends to 100k with the pot at maximum resistance. A rotary switch (set for 10 positions) is used to select the series resistance. The switch is shown set for 50k, giving a range from 50k - 60k with the pot.

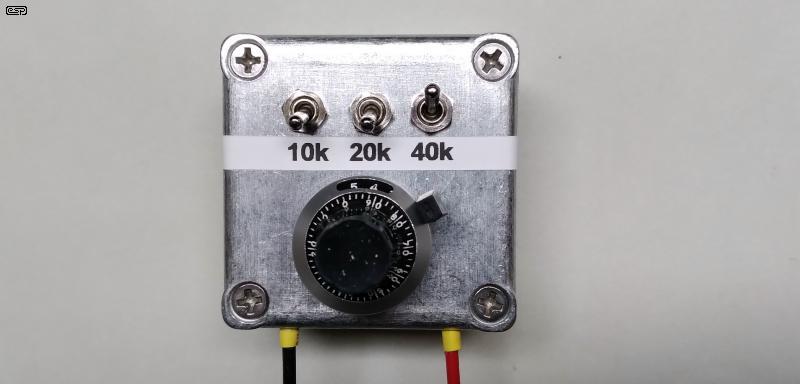

The compact version shown above has two fewer resistors, and extends from ≈100Ω to 80k. Three mini-toggle switches select an extra 10k, 20k or 40k, and they can be used in any combination. That means that all resistances up to 80k (with the pot at maximum resistance) are covered. It's a bit less intuitive than the full version with the rotary switch, but it's the version I built for myself. The resistor saving is immaterial, but the 3 mini-toggle switches take up less space than the rotary switch.

Opening a switch places that resistance in circuit. For example, to get between 30k and 40k, Sw1 and Sw2 are opened (30k) and the pot provides any resistance between 30k and 40k. 50k (minimum) is selected with Sw1 and Sw3 open. With all switches closed the resistance is determined only by the pot. It's up to you whether to use banana sockets or fixed leads (with alligator clips). Sockets are more flexible, but you'll need a very short test lead or the wiring will pick up hum. I dislike fixed leads, but I elected to use them on my unit as they are only ≈200mm long.

Rather than a rotary switch or mini-toggles, you could use a DIP switch, with as many positions as you think you'll need. They are small and a bit fiddly though, and I prefer the mini-toggle switches. DIP switches are also a nuisance to mount. You can use whatever you have to hand, as it doesn't need to be glamorous because it's a piece of test gear.

Not many circuits need very accurate resistors, and I recommend 1% metal film types as a matter of course. One place accurate resistance can make a difference is balanced circuits (input or output), where even seemingly inconsequential resistor mismatches can cause a large variation in common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR). As little as 1Ω can unbalance a differential amplifier with 10k resistors. In an 'ideal' unity gain differential circuit (never realised in practice but easily simulated), 1Ω reduces CMRR from close to infinity to a 'mere' 86dB. 10Ω reduces that by another 20dB (to 66dB).

Using 1% tolerance resistors in a balanced line driver or receiver means that the average CMRR is around 46dB (100Ω variance), but in reality this only applies at low frequencies. See Balanced Inputs & Outputs - The Things No-One Tells You. You can use this project to achieve near perfect balance, limited only by the resolution of the pot. My tests show that you can achieve close to perfect balance (I was unable to measure the residual with any accuracy).

The photo shows my unit, and the dial indicates that the resistance should be 34.92k. Measurement says 35.02k, an error of less than 0.3% (+100Ω). The three switches select the series fixed resistors and the pot adds from zero to 10k to the total. The dial is reasonably accurate, so you can get a rough idea of the total resistance from the vernier. I verified that it's easy to get within 0.1% (e.g. ±15Ω in 15k, and with care you can get even better. Most importantly, you can adjust the pot to get the resistance needed for your circuit. However, if you happen to need exactly 10k (or its multiples) you're reliant on the accuracy of the fixed resistors. In most cases this shouldn't be a problem, but you do need to be aware of it.

The capacitance from either or both leads to the case is 15pF, so it's unlikely to cause any issues at audio frequencies. If I need the case to be grounded to prevent hum pickup, an alligator clip lead can be attached to any of the switch toggles. I did contemplate a dedicated grounding pin, but decided it wasn't worth the extra trouble. The inside of the box is fairly bare, even though I went a bit overboard and provided 2W on the 10k range, using four 10k resistors in series/ parallel. This isn't essential of course, but test equipment (even very simple things like this) often get used in 'interesting' ways that we can't predict when putting it together.

The biggest benefit of this project is that it can be made very small - much smaller than a 'traditional' resistor substitution box. This minimises hum pickup, stray capacitance and inductance, and the box itself can be shielded with an extra ground wire so it keeps external noise pickup to the minimum. Adding shielding will increase stray capacitance though. Mine is in a small diecast box (51 x 51 x 33mm).

Once upon a time one could purchase 'resistance wheels' that used a multi-way switch to select one of 20 or so resistors. These are no more. They were handy, but definitely not high precision. This unit covers a similar range, but is intended to be accurate and stable when operated within its limits.

Unlike a more traditional resistance substitution box where the values are switched in decades and you can (supposedly) read off the exact value from the switches, this only applies if all resistors are very close tolerance. Of course you can buy resistance substitution boxes fairly cheaply, but you often don't know what dissipation (or current) is allowable. If the resistors are all SMD (surface mount) which is common now, the allowable dissipation/ current may be much lower than hoped for. Accuracy is unknown until you buy one and test it.

This mini-project came about because I had a 10k multi-turn pot left over after I build the distortion measurement system shown in Project 232. I don't use resistor substitution boxes very often, but that's mainly due to their physical size (most are really big by comparison). I certainly don't expect to use this every day, but I've often found a need to be able to select a very accurate resistance during experiments. This will save the hassle of finding a suitable pot and physically wiring it into the circuit under test.

There are no references for this project since there's nothing new about the circuits, and they both use fundamental principles. However, it's still a handy piece of test gear that you won't see elsewhere.

Main Index Main Index

Projects Index Projects Index

|