|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 105 |

The electrostatic panels described here are not available, and it is not expected that this will change. The set of articles has been retained for interest only, so please do not ask questions or ask about prices or availability - there is no point because the panels are not available. The material shown is maintained for 'historical' reasons only, as it may be of interest to some people.

ESLs (Electrostatic Loudspeakers) have a definite aura about them, and it has nothing to do with the high voltage used to polarise the panels.

A minimum system would use two panels per side, but 4 panels will give better results - as always, your listening environment and preferred level will dictate the limits of what is achievable. As with all ESLs, these panels are bipolar (i.e. dipoles), radiating from the back just as well as from the front. Damping material (e.g. felt) is required behind the panels to suppress the fundamental resonance. You may also consider adding a layer of standard speaker stuffing (polyester fill material) to further reduce rear radiation and possible resonance. The completed panels should be protected from dust accumulation by means of a suitable grille, which will also keep fingers away from the front stator - this can reach quite high voltages during loud passages.

Please Note: The information below is included for posterity, and the panels, EHT supply and transformers are not available.

There are not many DIY ESL systems, and most that do exist expect you to have large flat work surfaces, and do all the assembly yourself. Not so with these panels - measuring just 100 x 200mm (just under 4" x 8"), and less than 10mm thick, the original idea was that they would be supplied fully assembled, tested and working, along with complete plans for a suitable mounting baffle, resonance suppression, etc. Also available will be the EHT supply (ready made or in kit form) and pre-wired and potted transformers to match the panels to an amplifier.

As most readers will already know, there are power amplifiers and crossover networks available on the ESP site, so it is possible to build a complete system - as always, you can choose the exact system topology to suit your needs. The most appropriate crossover is the Project 09, a Linkwitz Riley crossover with 24dB/octave rolloff and phase coherence across the crossover frequency. Although the panels are reasonably efficient, they are not an especially easy load, particularly at high frequencies. Any power amplifier used with ESLs needs to be very tolerant of the rather unique load presented by the capacitive panels fed by transformers.

Figure 1 - An Electro-Static Loudspeaker Panel (ESP1)

The panel is was designated ESP1 - Electro-Static Panel #1 in case you were wondering. As you can see, it is fully made, with connection lugs for the balanced audio connection and the 1,500V EHT polarising supply. Unlike many other ESL projects, these panels have much closer spacing between the stators and diaphragm than most, so need a lower polarising voltage for reasonable efficiency. This does impact the bass performance, but it is recommended that the panels be used in conjunction with a cone loudspeaker woofer. A transmission line design is ideal, but these tend to be rather large and difficult to make, and the design presented will use a conventional sealed enclosure with optional equalisation to reach the lowest frequencies desired.

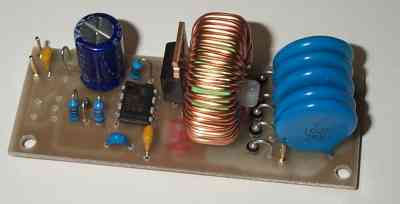

Figure 2 - The EHT Supply Prototype Board

The EHT supply uses a small switchmode supply, having an on-board regulator (not installed on the prototype) and a flyback high voltage generator circuit. The 500V pulse output from the flyback circuit then goes to a voltage multiplier to obtain the required 1.5kV to polarise the diaphragm. The voltage multiplier is the section on the right, with the large blue capacitors (each is 10nF, 3kV). Because the supply operates at 35kHz, the rather small capacitance still provides excellent smoothing - ripple is extremely low, even when loaded by 20 Megohms (this causes a much higher load current than the panels ever will).

I have experimented with vacuum impregnation and potting for the transformers, but ultimately decided that unless such a process is set up for full production, the effort is far in excess of what can be charged for the finished item. There is no doubt that the process works (and works well), but it is too labour intensive. Full details of the transformers used for prototyping and the suggested arrangement for a final unit are not available.

There seems to be some mystery as to the wiring of electrostatic speakers, but the wiring scheme is very simple. The transformer used must be centre-tapped to provide a return path for the polarising voltage, but that is no challenge. The ESL wiring diagram is shown below.

Figure 4 - Wiring Diagram For ESL Panels

Not a lot to it, as you can see. There is a 2.2 Ohm (* at least 5W recommended, and it must be non-inductive) resistor at the input to the transformers, to isolate them from the amplifier ... at least to a degree. Amplifier DC offset is important for this application, and it must be as low as possible due to the low DC resistance of the transformer primary winding (approximately 0.4 Ohm). Although the additional resistance helps, considerable current can flow with even a small DC offset. The transformers have a combined step-up ratio of 100:1 - each Volt of applied signal generates 100V at the secondary. A 100W amplifier (as rated into 8 ohms) will generate almost 30V RMS, so the transformer output will be close to 3kV RMS. This is not to be messed with! This should also be considered the upper limit for normal operation.

The 2.2 Ohm non-inductive resistor can be conveniently made using 1W carbon resistors - you can use 5 x 10 Ohm 1W resistors in parallel (2 Ohms), or (and this would be my preference) 10 x 22 Ohm resistors in parallel. Keep the resistors separated from each other to allow airflow and better cooling.

The diaphragm is polarised to 1.5kV, and is attracted to one stator and repelled by the other - a true push-pull system. This occurs in sympathy with the applied audio signal, and the diaphragm movement (minuscule though it may be) generates the sound. The diaphragm resistance is carefully controlled, and must be as high as possible. This prevents a phenomenon called 'charge migration', which increases distortion and also increases the risk of damage if the diaphragm arcs to a stator.

The recommended supply and wiring polarises the diaphragm as negative with respect to the stators, and a positive going input signal should cause a positive air pressure change in front of the diaphragm. This means that the rear stator would be wired to the Black transformer lead, and the front stator to the Yellow lead. As the rear stator is made negative it will repel the (negatively charged) diaphragm, while the front stator will become positive, attracting the diaphragm. This is reversed for a negative-going input signal.

Figure 5 - EHT Circuit

The EHT generator is quite simple, but needs to have good insulation from any nearby metal. VR1 is used to set the EHT to 1.5kV, and once set it remains very stable. As shown, the voltage applied to the flyback converter is variable from 1.25V to about 12.6V, but normally around 8V gives the correct output voltage. A full feedback regulation system is not needed, and only serves to make the circuit more complex. Note that the diodes must be rated at a minimum of 1kV, and must also be high speed types (such as the so-called 'Ultra Fast' UF4007). Although the MOSFET requires no heatsink, the regulator will get quite warm, since the circuit draws about 200mA in normal use. A small heatsink is recommended. A 15V DC plugpack (wall wart) power supply is quite adequate to power the EHT generator, or you may build your own supply with a 12V transformer, 4 x 1A diodes and a suitably large (about 2200uF) filter cap. The output voltage is measured indirectly, as 1,500V is beyond the range of most meters, and the meter will load the supply excessively (even at 20MΩ impedance). By measuring at the cathode of D2, loading is minimised. The voltage should be 500V for 1.5kV output. Note that the inductor value is tentative - it is subject to change depending on available coils and some further tests.

Warning ! The 1.5kV may only be low current, but it still packs quite a wallop (says he from personal experience). Always discharge the EHT before working on any part of the circuit.

A description of any loudspeaker is rather incomplete without response graphs, and the following give some idea of performance. Two panels were used for these tests, using a 48dB/ octave rolloff at 500Hz.

Figure 6 - Response at 1 Metre & 2.83V RMS

From this you can see that the equivalent sensitivity is about 85dB/m/W - this is a little lower than most cone speakers as is to be expected. As you can see from the graph, minimal smoothing was applied - the notch at just under 700Hz is a workshop artifact, and is not the panel's response. This is also the reason for the various ripples in response below 2kHz. Normally, these can be minimised by close microphone positioning, but that technique does not work with an ESL.

Figure 7 - Response at 500mm & 2.83V RMS

This is about as close as I could measure before phase cancellations caused by the length of the panel caused problems. It is very flat, and again, all dips and bumps below 2kHz are the result of room and object reflections. Where the previous graph was smoothed (1/12 Octave), this graph has no smoothing at all.

Figure 8 - Impedance Vs. Frequency

This graph is somewhat misleading, despite the fact that it is completely real. The problem is that there is a transformer with capacitive loading, and this is reflected in the impedance graph. The impedance actually changes depending on the source impedance, and since Clio uses a 1k Ohm test impedance the resonance point is shown much, much lower than it really is. This is a part of the complexity of the load as seen by an amplifier - it is very different from the normal response seen. When driven from a low impedance source, the impedance peak is flattened and raised in frequency. I have yet to figure out the best way to measure it (although I have several ideas).

Full construction details will not be provided. The initial tests were very encouraging as seen above, with extremely linear frequency response extending well past my measurement limits. However, the panels are difficult to build, the transformers require vacuum impregnation to prevent corona discharge (which damages the insulation), and it's all too hard for most DIY people. Attempting to support prospective builders is not something I'm prepared to do - there are too many variables and not much prospect of a worthwhile outcome.

The woofer section will always be tricky. While a vented box system might appeal to some, it will not be a good match to the ESLs, because of the relatively poor transient response. A sealed woofer is preferred, as its transient response is much better, and it will blend in with the ESLs much more readily. Having the drivers in a complete system matched for transient response is important so that the overall balance is ... well ... balanced.

There is ample opportunity for builders to experiment with a dipole woofer to match the dipole response of the ESL panels. This is probably the optimum arrangement, but does require equalisation to get the bass performance up to a reasonable level. This (of course) imposes additional challenges, the most irksome being that the higher cone excursions required by a dipole woofer mean greater intermodulation distortion. There is no easy solution to this, and many of the high excursion woofers have relatively poor performance - low efficiency being the biggest problem.

Main Index

Main Index

Projects Index

Projects Index