|

| Elliott Sound Products | The Whys And Wherefores of Guitar, Bass and Keyboard Amps |

Main Index

Main Index

Articles Index

Articles Index

In the studio and on stage, instrument amplifiers are vitally important to the musician. Specialised equipment is a necessity, and the instruments themselves are becoming more and more demanding of the amplifier-speaker combination with which they are used,. The size and power ratings of such systems has grown considerably in recent years; it is not uncommon to find instrument amps today, which are more complex and larger than a band's entire PA system of a few years ago. As one of the most controversial pieces of amplification ever produced, we shall first take a look at the guitar amplifier, which has evolved from a general purpose 'as long as it works' device, to a sophisticated piece of equipment - at least in the professional sector, where the so-called 'universal' amplifier is no longer relevant.

Most guitarists will say that, with a given amplifier, a certain volume level is required to obtain the right sound. While this is to a point psychological, there are very good technical reasons to support this statement. The 'right sound' usually means a fairly high level of harmonic distortion, both from amplifiers and speakers - distortion which gives much needed assistance to an electric guitar by providing the missing harmonics and increased sustain. A certain amount of sustain is obtained by acoustic feedback, particularly with semi-acoustic guitars, however the majority is the result of the amp being driven into 'clipping', or distortion. This has the effect of maintaining the level at a (more or less) constant level for much longer than would normally be the case (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Power Vs. Clipping

If an amplifier is overdriven, the sound produced is usually considered objectionable, so special measures must be taken to obtain the desired characteristics.

Firstly, there is the bandwidth restriction of the speaker cabinet. For the low-end this may be achieved by using an open-back box, to allow bass cancellation, or to contain the speakers in an enclosure of limited internal capacity. High-end roll-off is usually a characteristic of the speakers themselves: speakers - without 'whizzer' cones or aluminium domes will generally sound smoother because of their limited high frequency response. A broad peak in the speaker's response at 2kHz to 4kHz adds 'presence' and bite, and the response should roll off beyond that point. It is preferable that frequencies above about 7kHz are not reproduced at all, as this will exclude the 7th harmonic (which is discordant) of all strings of the guitar. Damping or venting of guitar speaker enclosures is usually avoided like the plague because damping will lower colouration, a desirable feature in musical instrument amplification. Without colouration all plucked string instruments, for example, would sound much the same.

Vented boxes are avoided because they emphasise (or allow to be reproduced) the lower frequencies - these are usually not desired, since they tend to muddy the sound. This is especially true for 'heavy metal' playing styles, since severe amp overdrive is commonly used to achieve the sound, and even small amounts of low frequency material (such as string handling) will cause large amounts of bass 'waffle'.

The majority of guitar speaker boxes (as noted above) are either open backed, or are relatively small sealed enclosures. There are naturally exceptions, but even 20 years after this article was first written, are still uncommon. This is not expected to change.

Additional bandwidth restrictions are usually designed into the output transformer of valve amplifiers. Transistor amplifiers usually do not have an output transformer, so this method of filtering is precluded. The effect of all this manipulation of response is to 'clean up' the distorted output waveform of the overdriven amplifier - the sound will become less harsh, and the transition from overdriven to 'clean' becomes less apparent.

In fact in a valve amp the clean or 'no distortion' state exists only when there is no input. Distortion is present even at low levels, and increases with the input signal. At low levels it's usually not apparent, and will usually remain below 1-2% THD up to around half-power.

The above situation is in contrast with the majority of transistor amps, which generally have very low distortion up to the point of clipping, after which distortion rises rapidly. Maximum distortion is the same as for a valve amp - i.e. a square wave, but the transition is such as to be more noticeable. This can be objectionable when the guitarist is playing clean but for the odd note or chord which overdrives the amp, causing a marked change in tonality (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Distortion Vs. Power

Output impedance and 'dynamic output' are other major contributors to the sound of a guitar amp. Output impedance, in this instance, has nothing to do with speaker 'ohmage', but is the actual source impedance of the amplifier, as seen by the speaker. In a valve amp, the source impedance may be as high as 200 ohms for a nominal 8 ohm output [See Note]. This allows the speaker freedom to exhibit its own natural resonances, plus the colouration provided by the enclosure itself. A low output impedance on the other hand, will repress colouration by damping the speaker, in much the same way as would fibreglass in the cabinet. This tends to make the amp sound flat and lifeless, lacking the subtle colouration and tonality which makes a fine musical instrument - and after all, a guitar amplifier is as much a musical instrument as the guitar itself. Transistor amps usually have a low source impedance, typically less that 1 Ohm.

It should be noted that the power rating for guitar amps is (very) commonly quoted at 10% distortion. This means that a 100W amp is typically about 80W at the onset of clipping (usually taken as the 'real' maximum power level). This is justified on the basis that few guitarists will operate their amps with no distortion at all. This assumption is not necessarily valid, but has prevailed for a very long time, so is unlikely to change now.

Note: The source impedance of valve amplifiers is generally lower than that quoted above, and in fact it will generally match the speaker impedance (assuming no feedback is applied). I appear to have goofed in the original article.

From the very first guitar amplifiers I ever built using transistor output stages, I used current feedback to increase the output impedance of the amp. This restores much of the 'valve sound', and provides a simple but effective method of providing short-term short circuit protection (for example while plugging 6.5mm phone jacks into their sockets while the amp is on). This technique has now been adopted by nearly all guitar amp manufacturers. Regrettably, this technique does little to improve dynamic output. Output impedance of my amps was typically 200 Ohms.

Dynamic output in this context means the ability of an amplifier to deliver power to the load (the loudspeaker). Because of the high source impedance and low efficiency of valves, output transformer and the power supply, a valve amp is capable of developing approximately 75% of its rated power into double its rated impedance, and up to 50% of rated power into four times rated load. This means the amp can provide relatively constant power regardless of the variations of impedance with frequency which are a characteristic of speaker loads.

In contrast, a transistor amp can usually deliver only 55% or so of its rated power into double its rated load, and about 30% into four times rated load. These variations may not appear to amount to very much, but they do make a difference in terms of spectral balance and dynamic performance. Such is the difference in fact (and this also applies to valve hi-fi amps, bass amps, etc) that a 100 watt valve amp may be considered to sound as loud as a 150 watt transistor amp. However, the difference is only 1.76dB, but that is audible amongst other amps as it affects the overall balance of the instruments.

The technical reader with an understanding of dB and the logarithmic response of the human ear may be sceptical about the foregoing paragraph, but differences of 1dB are audible when one has a suitable point of reference; in musical groups, where the balance of instruments is critical, such differences are very noticeable.

The level of sound produced by a guitar amp is usually way out of proportion to the quoted power rating. For example, a 100 watt guitar amplifier played normally (for a rock guitarist) will produce an average sound pressure level of about 120 dB at 1 metre. Try that with your hi-fi and you will most likely have speaker cones (and/ or your neighbour's projectiles) all over the listening room floor. The reason is quite simple. Because the amp is being overdriven, peak limiting will occur - clipping of the output waveform - which reduces the peak to-average power ratio of the program material. The peak to average ratio of a guitar signal is about 20 dB; that is, the peak level as a note or chord is struck will be 100 times higher than the overall average level. An overdriven amplifier may reduce this ratio to 2:1 (3 dB) or less, and as a result the average power is higher.

A further power increase results from the fact that a severely clipped waveform will approach a square wave, which has twice the power of a sinewave of the same amplitude. The result is a 100 watt amplifier delivering an average power of perhaps 170 watts short term (i.e. maximum level indicated on a VU meter), and up to 130 watts averaged over a 5 to 10 second period.

Compare this with an undistorted amp handling program with a peak-to-average ratio of 10:1 (10dB). The long term average power will be in the order of 5 to 10 watts with peaks of 100 watts. With mild distortion, say less than 15%, the average power climbs rapidly to around 25 watts; increase the distortion further and the power climbs again until, with maximum overdrive, a 100 watt amp will be delivering 200 watts!

An important point was raised by a reader, who said that the above explanation only applies if the power supply remains at a constant voltage with the increased load. This is very true, and in reality, most don't, so the maximum power is limited by the capabilities of the power supply. Valve amps are usually worse in this respect than transistor amps, and the maximum power at full clipping may only be 150% of the rated power.

Despite this, the average SPL (Sound Pressure Level) is maintained at a high level, and the effect is that it sounds louder than one might imagine it should. This is similar to using compression (as done with ads on TV). The maximum SPL is not increased, but because everything is at maximum, it sounds louder than it really is.

So loud, in fact, are many popular guitar amps, that guitarists often experiment with methods of obtaining 'the sound' at lower power levels. There has been a trend for some time now towards smaller amps and/ or some provision for simulating amplifier overload. The latter is best achieved by using a master volume control and some form of clipping circuit, which should ideally be placed (electrically) between the tone controls and the power stage. A clipping circuit placed before the tone controls will not sound like amp overload because of the large amount of treble boost built into guitar amps. A clipping circuit so placed will produce only the dreaded fuzz box sound, once much loved but now generally disdained because of its harsh unnatural sound. Of course, some guitarists still like it.

Having said that, there seems to be a resurgence of old analogue technologies in all areas of electronic music, and this includes the lowly fuzz box. There have also been moves to try to emulate the asymmetrical clipping characteristics of valves (some dating back many years).

One of the most innovative (and complex) attempts to recreate the valve sound with solid state electronics is the Vox AC30 Simulator - a contributed article on the ESP Project Pages. Unfortunately this was withdrawn at the author's request. However, Project 27 remains an excellent 'all rounder' guitar amp, and is highly recommended.

The addition of a graphic equaliser set, now incorporated in many brands such as the Zoom (above), greatly expands the tonal variation possibilities of an amplifier.

Many of the requirements for guitar amps also apply to bass amplifiers, in particular those factors relating to colouration and harmonic distortion provided the latter is not obtained from amp overload. A high output impedance and high dynamic output are also desirable features.

One of the major differences is the power requirements. Whereas a guitar amp will usually be overdriven, a bass amp should not be. The sound will become muddy and indistinct, lacking punch and definition. Bass is, by its very nature, difficult to reproduce. The open E string for example, has a fundamental frequency of 41.2 Hz, a difficult frequency to reproduce even given ideal circumstances, let alone at high power and with enclosures which must be able to be moved around! As a result, few bass systems have appreciable output below about 80Hz - and this includes the large 'W' bins used for PA systems. Up to four times as much power may be needed at 40Hz to match the acoustic output at 400Hz (Table 1).

Because it is (usually) undesirable to drive a bass amp into distortion, and the bass should be able to equal the guitar in volume, much more power is required for bass than for guitar. In fact if we assume a guitar amp rated at 100 watts and operating at an average power of 130 watts, and assume a bare minimum bass peak-to-average signal ratio of 10:1 (10 dB), our bass amp would need to be at least 1000 watts to match the guitar amp without producing audible distortion! A certain amount of clipping of transients is permissible, and in a well designed system will not be audible because of the masking effect of the rest of the band. It will, however, be very audible on a bass solo if the same volume is used.

Harmonic distortion in the bass region is usually very high, especially in the speakers. Some are capable of a total harmonic distortion approaching 100%! This 'impossible' distortion level is caused by speaker 'doubling' - the result of a combination of speaker-cone breakup, voice coils which actually leave the magnetic gap and poorly designed enclosures. The main faults in enclosures are truncated horns, excessive horn flare rates, badly vented cabinets, and poor internal bracing of cabinets which are often simply too small for the speaker. Intermodulation distortion arises from the large excursions of a speaker cone at bass frequencies which cause the voice coil to partially leave the magnetic gap. When this occurs, efficiency is lost and distortion appears at the peaks of the waveform. Any superimposed high frequencies (harmonics) will also be distorted.

It must be noted that many of these problems have been reduced with modern loudspeaker drivers, whose excursion is often prodigious. Linear cone travel of +/-10mm or more is not uncommon now, and there are many very efficient speakers that are specifically designed for use in small enclosures. Coupled with the very high powers that are common today, it is possible to make a bass amp that will faithfully reproduce down to 30Hz in a cabinet that is still portable.

It should now be apparent that a 200 watt bass amp, typical of many systems, is quite inadequate for a reasonably loud rock band, and in fact is often barely adequate for a club band; it will usually be pushed so hard that it will be clipping for up to 60% of the time. If we now connect the above amplifier to a speaker system whose efficiency, especially at the lower frequencies, is not very high, add equalisation to provide a measure of bass boost, then the amp overload problem becomes even worse.

The obvious solution is to use more speakers in larger enclosures - and more of them - driven by even more powerful amplifiers. An effective alternative is bi-amping; an electronic cross-over separates amp-speaker combinations which may be more easily optimised for the frequency range being covered. This approach has been used with some success, and although it is more costly it will eventually become a standard technique. The advantages of a bi-amped system are lower intermodulation distortion, and greater acoustic output for the same total power as a conventional amp/speaker combination.

Unfortunately there are many trade-offs which must be made, both for financial and physical reasons, and many of the better combinations are precluded by prejudice. For example, the average bass players' opinion of 300mm (12") speakers is not printable ... well, this used to be the case when this was first written, but many bass players use 250mm (10") speakers these days. Things have changed in some areas.

A variation on bi-amping is to use separate amps and speakers for a stereo bass guitar. In this arrangement the bass and treble pick-ups on the instrument are brought out separately and fed to separate amps. This technique has been around for many years but as few instruments are wired for stereo, most bass players have not had the opportunity to experiment with it. Any two pick-up bass can be easily modified however, and it is a trick well worth trying.

A modem keyboard setup is probably the most complex and expensive item in any band, with the possible exception of the main PA system.

The basic requirements, at least insofar as the bass and midrange are concerned, are much the same as for bass amplifiers. Power requirements are of the same order, and similar problems involving loss of definition may occur due to insufficient power, poor enclosure design and a lack of understanding of the demands which are placed on a keyboard system. These include the extreme dynamic range (if pianos, the vast pitch range of synthesisers, and the special difficulties presented by such instruments as string ensembles, Mellotrons and Leslie type organ speaker cabinets (which are usually not loud enough unless miked).

Mellotron?? I'm not going to even try to explain this one (you wouldn't believe me unless you were there). Try a web search, you might well be surprised.

The majority of intelligence and energy of keyboards is in the mid-range, the band of frequencies from about 180Hz to 1200Hz (Roughly F3 to D6) that cover the fundamental frequencies of the most used section of any keyboard instrument. If this section is not treated with the respect it deserves, it will be difficult to obtain a good, clean sound from the majority of instruments.

Obviously, the power required will depend on the volume at which the musician intends to play, but 100 watts is a minimum for all but the quietest bands. In a rock band this may have to be increased to around 1000 watts, with perhaps 500 watts on bass, 400 watts on midrange and 100 watts for treble.

Modern setups will almost always have a direct feed to the FOH (front of house) mixer, often with each instrument having its own channel so the mix can be balanced properly. Keyboard 'monitoring' can be via a separate mixer and amp on stage, via a separate fold-back system with the mix created from the FOH system, or both.

An exclusively mid-range enclosure should not use speakers larger than 300mm (12') if a good transient response is to be obtained, and a flat frequency response is desirable.

| Bass Boost | Power |

| Ref. 440 Hz Level | Ref. 100W @ 440 Hz |

| 0dB | 100 W |

| 1dB | 126 W |

| 2dB | 158 W |

| 3dB | 200 W |

| 4dB | 250 W |

| 5dB | 316 W |

| 6dB | 400 W |

| 12dB | 1600 W |

| Table 1. The right column shows the power equivalent to the bass boost in the left column, referenced to 100 watts at 440 Hz (A above middle C). | |

Horn loading is an excellent way of achieving high efficiency, and if properly designed will provide low distortion, good frequency response and excellent transient response. The bass enclosure normally should not be horn loaded, because a horn which will work properly down to the lowest frequencies will be too large. Instead a reasonable sized vented enclosure can be used.

A better alternative today would be to use a sealed and equalised enclosure (see the EAS subwoofer project on the ESP Project Pages). This will give the best transient response, but requires much more power. On the positive side, the box will be very much smaller than would otherwise be possible.

The high frequency end of the spectrum needs careful design, and must be protected from high power at high frequencies which the synthesiser, in particular, is capable of producing. (A synthesiser is the only instrument able to develop the same power at 20kHz as at 40Hz). Some form of protection for the high frequency drivers is therefore desirable, and becomes essential if H.F. horns are used. Such protection will also assist the musician in retaining his/her hearing (although from personal experience I can assure the reader that hearing retention is unlikely).

Passive crossovers are not recommended for high power keyboard systems except at the top end, from horns to 'ring-radiators', where they will provide the most cost-effective solution without loss of performance. In general, though, their excessive power loss and the difficulty of optimising the crossover points makes them undesirable. A large keyboard system, then, is basically a very large hi-fi, with colouration being something to be avoided. It is not, or should not, be an extension of the instrument because of the number of different instruments which must be accommodated. Any colouration which is introduced should therefore be controlled by the musician.

Equalisation circuits are used in nearly all forms of amplification, and some have become very sophisticated. The old faithful bass and treble controls still exist, but the majority of mixers and amplifiers now have additional controls. Midrange and 'bright' have been with us for some time, as has the presence control and graphic equalisers and semi parametric EQ are now being more widely used.

The range of effects available is enormous and growing; the echo, reverb and tremolo of yesteryear have been joined by esoteric devices like automatic double tracking ('ADT') digital delays, phasing, flanging, chorus, true vibrato (frequency modulation), peak limiters, compressors, harmonisers etc., etc.

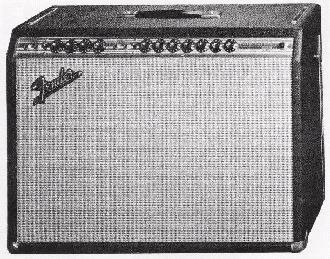

The simplicity of an amp like the classic Fender Twin Reverb (above) still appeals to many musicians. The Twin Reverb is used by both rock and jazz guitarists, and is also popular with electric piano players.

More important now than ever before are leads and terminations. Cannon type connectors are replacing 6.5mm jacks on most equipment, and some guitarists are changing over to Cannons because of their greater reliability. Heavy duty, low loss cables are being widely used, providing less noise and lower failure rate than standard cable, which responds poorly to having a 200kg rack of power amps wheeled over it.

Although there was (at the time of writing) a tendency for guitarists to use Cannon (XLR) connectors, this movement has seemingly died. This is a shame, since they are far more robust and reliable than 6.5mm jacks. There are, however, a number of professional locking 6.5mm phone plugs and jacks available, that did not exist when the article was written. For speaker leads, Speakon plugs and sockets are now available which outperform the other connectors in all respects. Many guitar amps still rely on jack leads for speakers.

Well, there you have it. If some of the points made here prove contentious, so much the better, for it will stimulate discussion and debate, both of which go towards a greater understanding of the problems of instrument and amplification. With a better knowledge of the needs of musicians, the technical persons amongst us will be better able to analyse the difficulties encountered by players, be able to pinpoint and maybe even eliminate them. On the other hand, a little technical knowledge will assist the musician in describing his problems, and will be very helpful to the technician or engineer who is expected to solve them, often without even knowing what they may be.

Additional notes and comments have been added where appropriate (using indented italics), but for the most part the article is as originally written. The byline above was true at the time, but is now way past its 'use by' date - except for Elliott Sound Products, which is very much alive. The scariest part is that this was so long ago!

PLEASE NOTE: The inclusion of two photographs of guitar amplifiers shall not be taken as an endorsement of the brands featured, nor shall this statement imply any criticism of same. They were included in the original article, and are thus reproduced here. No more, no less.

As of 2020, very little has changed. Most of the popular guitar amps are still available, often with design errors retained for posterity. There are several new designs using DSP (digital signal processing) for 'modelling' the sound of other amplifiers and speakers, but with that comes a dilemma - the DSP circuitry is built using modern DSP ICs which have a notoriously short manufacturing life, and on PCBs (printed circuit boards) that make extensive use of surface-mounted devices (SMD). These are difficult to repair even while the ICs used are still available, and impossible to repair once the specialised ICs are no longer made. Equipment that is expected to last for 20 years or more may only survive for 5 years before replacement PCBs are no longer offered by the manufacturer, meaning that the amplifier becomes so much scrap metal and timber.

There is still a lot to recommend a basic amplifier, with any specialised effects added externally. This should ensure that the amplifier itself can be repaired well into the future, and because the 'special effects' are external, the amp can still be used if the effects unit decides to die. In any amplifier where the effects are internal, a failure will usually render the whole amplifier inoperable. This doesn't fit well with the "The show must go on" philosophy of most musicians (and venue operators!). However, the economics of manufacture mean that most 'new' gear will have much (or most) of the circuitry using SMD parts, making service difficult or even impossible. Rather than replacing a 50c (or $5.00) part, SMD construction usually means replacement of a complete PCB that can only be obtained from the manufacturer.

Valve amplifiers are still usually made with 'traditional' techniques, that ensure that the amp can be repaired for as long as replacement valves are still available. However, as noted above, many have design flaws that have survived for as long as the design has been available. Sometimes, these are fixed, only to be re-introduced when a 're-issue' of an earlier model is made. Also, consider that many amplifiers that claim to be 'valve' only have one vacuum tube, whose aural influence is often negligible. The remainder of the circuit uses operational amplifiers (opamps) and/ or transistors, so many of the claimed benefits of valves are implied by the inclusion of a single 12AX7, but fail to deliver.

Most of the 'sound' of a valve amplifier is due to the output stage, and not the input stage(s) as is often believed. While there's a place for hybrid designs, it's not helpful to anyone when a valve is included as a token gesture. For example, adding a 12AX7 to a computer motherboard (and yes, it has been done) is not helpful and provides no benefits at all to the user. Wishful thinking will have some people imagining hey hear a difference, it's generally an illusion. Once someone knows that there's "a valve in there", the opportunities for self-deception are endless.

Main Index

Main Index

Articles Index

Articles Index