|

| Elliott Sound Products | Project 132 |

Andy has submitted this project, but it must be emphasised that it is to be used as a source for ideas for people with machining experience and equipment. There is a considerable amount of work involved, and great scope for either wasting lots of bits of aluminium and other materials, or creating your own variation.

At this stage, no drawings exist. Andy built his unit in the same way I do many of my projects, and worked out each detail as it presented itself. The photos give a very good view of the various parts and explain the functions. It is up to the constructor to assess the complexity of the project against his/her abilities to duplicate what Andy has already done.

The good part is that Andy has proved that the technique works, and has figured out the easiest way to achieve the desired results. This saves anyone else a great deal of time, trial and error.

It has been said that for the best reproduction of a record it should be played as it was cut ... on a linear tracking tonearm.

My early thoughts to build a linear tracking arm were to use a conventional pivot arm mounted on a motorized carriage. After considering possible noise transfer of the mechanism and a servo circuit that would only be playing catch-up with the grooves, while being close, would not always be right on.

As I later discovered air bearing tonearms, the need became obvious for an inexpensive do-it-yourself approach for those of us that lack the funds of upwards $70,000.00 for a Rockport turntable.

This project as with all others presented here at Elliott Sound Products is to encourage audiophiles that it is possible to make a quality piece of equipment yourself for considerably less than a commercially purchased unit. Its purpose is to share my ideas with other vinyl enthusiasts as an encouragement to fully exploit the potential of classic vinyl.

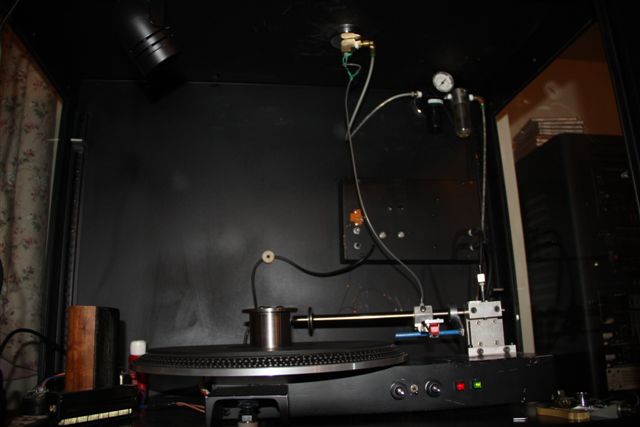

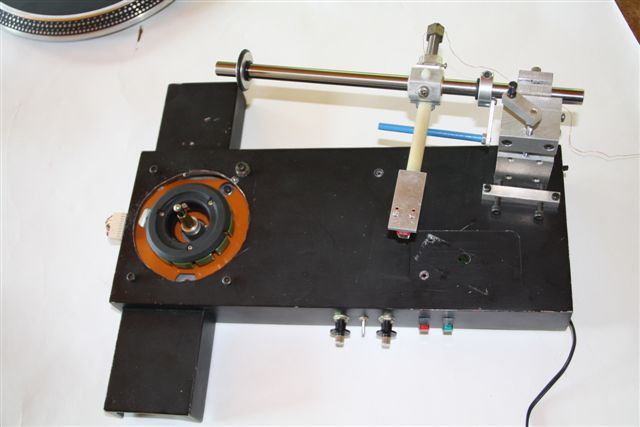

Figure 1 - Complete Linear Tracking Arm & Turntable

The ideas presented here require basic machining skills in the use of a metal lathe, milling machine, drill press, welder, layout tools, etc. This is not a step by step project; it only offers basic construction ideas and concepts, the rest us up to you. The end result depends on your creativity and the resources you have available. Sizes and dimensions of everything presented here were chosen at random or sized to whatever scrap and material already at hand.

The internet provides a gamut of information on tonearms and is recommended reading to provide all the necessary technical details and adjustments associated with them which needn't be repeated here.

One point to caution you when you bring your turntable in a workshop environment is that metal chips and dust will be attracted by the magnets in your cartridge and motor assembly. Don't say I didn't warn you! Keep them covered!

The heart of the tonearm is the air bearing. Start with a standard 1/2 X 3/4 X 1 1/8 inch long oilite bronze sintered bushing, (also known as self lubricating and SAE 841), the typical standard motor replacement type with an actual ID of .502" works best as it provides good clearance. Note that some industrial supply houses carry other sizes available with either slightly over or under bore sizes as well.

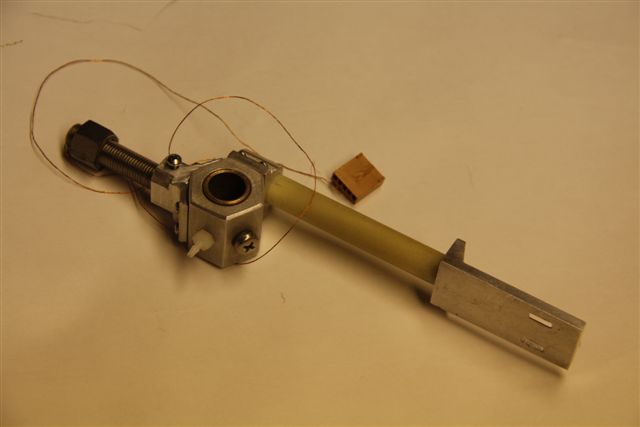

Figure 2 - Sintered Bearing Preparation

A temporary fixture as seen in Figure 2 is needed to be made with a pipe fitting on one end to seal the ends of the bushing without damaging it. The idea is to blow out all the impregnated "permanent" lube. I made my fixture with miscellaneous pipe fittings and cross drilled where it would end up inside the positioned bushing. Washers and gaskets were used to provide the seal with the bushing gently sandwiched in between. Crushing it or distorting the bushing in any way will render it useless. The 3/8-24 thread is close enough to a standard 1/8-27 pipe thread to attach to your workshop shop air compressor. Proceed to immerse this assembly in a container of boiling water until it heats up and pressurise with low pressure air. (Use caution to avoid burns!). Then clean with lacquer thinner to remove any residual lube. Your bushing will now be quite porous.

You may be curious to see how the bushing slides on the shaft. Don't be discouraged if it feels and sounds rough as it slides along because it will, When it is mounted and pressurized with air it will come to life as it will literally float on air.

The main body that the air bearing mounts into is 1 inch hex aluminum stock 1 inch long. It is machined with O-ring grooves in the ends as they provide an air tight seal holding the air bearing in place. The I.D. between the o-ring grooves is bored out slightly larger than the O.D. of the bearing to allow air flow around the bearing. A small tapped hole in the middle of a flat is needed for the miniature air supply fitting. The phillips head screw seen is used as a plug to fill an inadvertent hole.

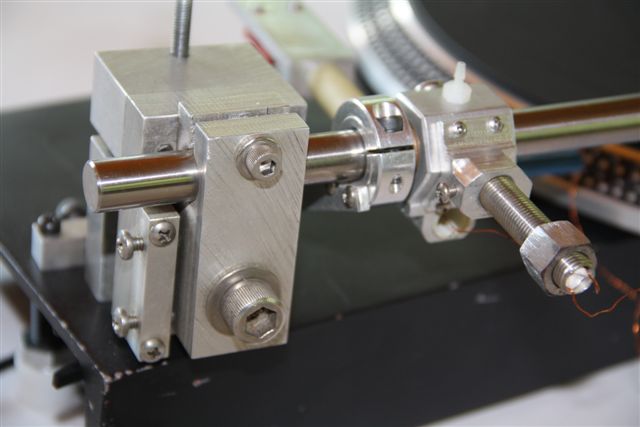

Figure 3 - The Complete Tonearm

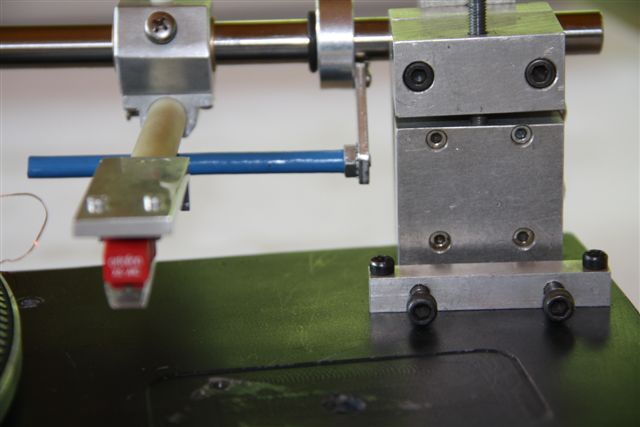

The tonearm tube is 7/16" O.D. G-10 fibreglass tubing drilled out to .312". The headshell is machined from aluminium which is press fit into the fibreglass tube and is a total of 9.5 grams and 5.25 inches long. The counterbalance threaded shaft is 3/8"-24 X 1.875" stainless steel drilled out to .282" and the counterbalance used is a hex nut at 9 grams.

Figure 4 - Air Bearing Detail

The cartridge wires currently used are single strands of AWG # 34 magnet wire, including a ground wire for the head shell and bonded to the bushing assembly and chassis. All together with the Ortofon XC-M5 cartridge this whole assembly weighs around 85 grams.

Figure 5 - Headshell Detail

The main shaft that the arm/hex body slides on is a 1/2" X 12" polished stainless steel shaft. Seen in the photos (Figures 6, 7 8 and 9) are the blocks which support the shaft. There are many ways the arm support can be made, but the essential requirements don't change. You need to be able to adjust the height above the disc surface, angle with respect to the disc platter, and angle with respect to the horizontal.

Figure 6 - Tonearm Support

Between those blocks is a small linear slide bearing with a 1/2" travel. This is to adjust the vertical tracking angle; you can see the adjusting screw on top. Other provisions are made to enable adjusting the angle of the shaft to be parallel with the platter. There is also the adjustment to pivot the whole support assembly for the stylus to track the alignment gauge properly. Also for these two adjustments are disc spring washers, A.K.A. Belleville washers (conical springs), placed under the screw heads to keep everything snug yet have the ability to make adjustments.

For those that may have a gun drill available (i.e. a specialised drill for long, straight holes such as for making gun barrels, not a pistol-grip drill) it would be suggested to drill out this shaft to accommodate wiring for an end of record shut off sensor. Depending on the grade of stainless steel used for the shaft, drilling may represent a significant challenge. While a linear slide bearing is not necessary, some provision to adjust the arm height is needed.

Figure 7 - Tonearm Support; Front View

Details for my mounting and adjusting methods of the arm base assembly are shown in the pictures. Also take note of the fabricated arm rest and tonearm stop mounted on the arm shaft. The arm stop has an o-ring around the periphery to protect the records from scratches (see Figure 10).

Figure 8 - Tonearm Support; Top View |  Figure 9 - Tonearm Support; Side View |

The donor turntable used was an old direct drive Technics. The motor is mounted on a plate beneath the 6 inch steel channel to give the platter a lower profile. Short 4 inch channel pieces are welded on to the shape of a tee. The steel channel as it comes from the mill may not be perfectly flat so A small milled pocket area to mount the arm base on is seen in the photos which is not utilized in this latest setup. This is to ensure that the arm base is mounted on a flat surface.

Figure 10 - Full View of Linear Tracking System

The motor drive circuit and other controls are mounted underneath. The power control used is an old school on/off latching relay configuration to some day incorporate an end of record shut off. Three swivel pads were used as the levelling feet.

Figure 11 - Donor Turntable Drive System Installed In Steel Channel

The air line fitting is mounted approximately 18 inches above the turntable and centred to the record grooves and uses .050" ID silicone tubing. Its length is enough to allow free movement yet not adding much resistance to the arm assembly. Remotely located is a small four cylinder air compressor pump driven by a 550W (3/4 hp) DC motor. The motor speed control and the pressure relief are adjusted for the air to start to bleed off at around 30 PSI. Mounted near the turntable is a filter to collect any dirt and condensation along with a pressure regulator. I generally have the pressure at about 25 PSI as anything above that seems to blow the tubing off the fittings. The air bearing needs at least 15 PSI for it to work smoothly. The air compressor pump provides a somewhat smooth output (as compared to a single cylinder) and the distance being far enough away that in my case (25 feet) there was no need to provide an air storage tank to smooth out the flow any further,using 1/4 inch tubing for the main air supply the length of it works well enough for that purpose.

A sacrificial record is needed to make an alignment gauge. Set this record upright on your surface plate and find the center of the hole with your height gauge and scribe a line across the grooves. It is important to find the center in this manner as splitting the 12 inch record diameter may not be accurate as the spindle hole may not be perfectly centered. This is assuming that the grooves are not eccentric relative to the spindle hole!

To make the tracking adjustment you need to pivot the main base shaft holder until the stylus exactly follows the scribed line across the grooves as the platter is kept stationary. It will take some trial and error as there is interaction between the pivoting and the platter position.

My newly acquired Cardas Audio test record was indispensable in assuring that the turntable and tonearm are properly leveled. While the record is very useful for its intended purpose I also found the wide areas between the recorded bands equally so. I place the stylus on the blank area of the record to adjust the shaft so that it is parallel to the platter so the arm stays still and does not skew off to either direction, (as the platter rotates!) similar to an anti-skating adjustment. This of course is also done after the platter is leveled. Another way to do this is to use a dial indicator to get the shaft parallel to the platter, then use the test record as mentioned above to adjust the level of the platter.

Using a Shure TTR 117 test record I found the tonearm resonance to be around 13 to 14 Hz.

With that figure and referring to web resources it indicates that the arm has a mass of 11 grams with my particular cartridge. Making the arm a bit heavier or longer shouldn't hurt as it will reduce the resonant frequency, as it is on the high side within the accepted desirable range.

As found on the web there are two schools of thought regarding the vertical tracking angle (VTA) adjustment. Some are adamant of the critical adjustment of the VTA while others say it's not an important issue; so far I have not noticed any sonic difference regardless of how much I crank the height up or down. No ideal sweet spot has ever been discovered. Perhaps the adjustment is critical with a conventional pivot arm (?).

While no scientific tests other than resonance have been done listening to the turntable was a pleasure as there is definitely a difference between this, my Technics SL 1500 MK II and a friends Linn table. Listening was done through my ESP DoZ headphone amp and AKG K1000 headphones. The conclusion was that the air bearing tonearm definitely sounded better. On quality recordings the sound was cleaner and more detailed. On one particular album I used to hear crosstalk from adjacent grooves; no crosstalk was evident with the linear tracking arm.

Warped records I have played so far were no problem as the arm tracks effortlessly.

However, poorly recorded albums that sounded lousy still sounded just as lousy, as it didn't provide any increased listening pleasure, no magic there.

A demonstration record can be made with the flipside of the alignment record by drilling a new center hole next to the existing one and play it to see how well the arm follows. A properly working arm will track effortlessly.

With all the listening I have done so far I find this tonearm has exceeded my expectations sonically as I look forward to some day experiment and refine it further and make it into something more cosmetically appealing. I find an auto shut off, cue control and finger lift as much needed options. A pressure switch to stop the platter in case of an air pressure failure would also be a good idea.

A future design in mind is to use a conventional removable headshell which will be a convenience for cartridge swapping.

Two excellent sources for hardware, parts and raw materials not commonly available are McMaster-Carr and MSC Industrial Supply. If you are not in the US, bear in mind that these may not be useful. I checked both carefully and found no reference to international shipping options.

It will be see that throughout this article, there is a mixture of imperial and metric nomenclature. No offense to Andy, but his countrymen seem to consider it completely normal to describe an object using mixed systems (one sees an implied example with an imperial (3/8") hex nut weighing 9 grams). I did not make the conversions to metric here for one simple reason - there are too many imperial sizes specified that do not have a direct metric equivalent, and some of the items may prove extremely hard to get outside the US anyway. Although it is possible to fabricate anything if you have the tools, most people don't.

Despite the obvious limitations created by any project that relies on US suppliers for needed items, the general principles can be applied anywhere. It might be necessary to salvage parts from old printers (often an excellent source for polished stainless steel rods of varying sizes) or the like, and the enterprising constructor might choose to make the air bearing rather than use the suggested sintered bushing. The primary reason for inclusion of the project was to show what can be done if you want one badly enough.

Main Index

Main Index

Projects Index

Projects Index